UVA’s Collection of Historic Dress Comes to Life

Deep in the bowels of the University of Virginia’s drama department dwell the ghosts of bygone eras. They linger in the …

Deep in the bowels of the University of Virginia’s drama department dwell the ghosts of bygone eras.

They linger in the wool of a man’s overcoat, the silk of an Edwardian gown, the cotton of a slave’s dress – each with a story to tell.

Drama Professor Gweneth West cultivates those stories as curator of UVA’s Collection of Historic Dress. Amid towering stacks of props, West extracts sheet-encased racks of iconic clothing from as early as the 1790s and as recently as the 1970s.

“Mounted on mannequins, these garments have so much personality. It’s very haunting,” West said. “You think about what clothes mean to us today, why we choose them and how we think about the impression we will make. Fashion is so much about who we are and who we dream to be. This collection gives us a glimpse into other peoples and other times through the fashions they wore and preserved for posterity.”

The collection’s 10,000-plus items primarily come from donations and estate sales. Former professor Lois Garren began the collection in the 1970s, realizing that some donated garments, too fragile for the stage, were valuable for study tools.

Today, students use the collection to pattern period costumes and research textiles, fashions and cultures. Each January Term, West teaches a course, available to all undergraduates, that showcases the collection, “The Fine Art of Dress: Conformity and Individuality.” She continues to grow the collection and seek new tools to preserve its aging garments.

Some garments are remarkable for their extraordinary finery, others for their unique insight into ordinary lives. Each offers students a slice of history that might have otherwise gone unnoticed.

This circa 1795 wool coat is the oldest piece in the collection and one of the country’s finest examples of 18th-century men’s tailoring, according to an evaluation by fashion historian Edward Maeder. A Charlottesville-area donor, Chris Devan, donated the coat shortly before his death, saying only that a relative “wore it over on the boat.” West assumed he meant a leisure cruise, but after dating the coat to 1795, realized that “over on the boat” meant the trans-Atlantic voyage from England to the fledgling United States.

Given the coat’s size, the owner was likely a young man, perhaps sent to America to make his fortune. The simple tailoring is characteristic of the 1790s during the French Revolution. Anyone with even moderate wealth did not want to be classed with the aristocracy being guillotined by the revolutionists. Men’s dress shed much of its ornamentation, adopting simple, well-tailored silhouettes in wool fabrics like this tan coat. Echoes of this silhouette and its focus on excellent tailoring are still seen in bespoke menswear today.

The dress at left, dating to circa 1826, likely belonged to a nanny and “wet nurse” caring for the children of an affluent family. The dress at right was probably worn by several slave women, beginning circa 1840. Given the quality of the tailoring, West believes it would have belonged to a house slave, perhaps with a simple Peter Pan collar, cuffs, apron and a hat added to make it more formal for an indoor servant. It has mismatched buttons, some dating circa1840 and others dating circa 1890. This, along with the adjustable waistband, indicates that the garment was passed down among many women and made to fit them at different life stages, from adolescence to childbearing to child rearing.

The nursing dress is sturdy, made of patterned beige cotton designed to mask stains accrued from child care and housework. At the time, it was very common for upper-middle and upper-class women to entrust breastfeeding and child care to a hired servant. In the folds of the gathered bodice, there is a small slit for nursing, which can be concealed when not needed. The dress also comes with a detachable caplet to make the nursing process more modest.

Famed couturier Charles Frederick Worth designed the silk and satin dress at left, dated to circa 1884. West likens the emerald green brocade and lace gown at right to something Dame Maggie Smith might wear while portraying the Dowager Countess of Grantham, one of the beloved characters on the popular British television series “Downton Abbey.” It was one of the garments West chose for the 2012 exhibition at Charlottesville’s Paramount Theater, where she displayed some of the collection in conjunction with her talk about the clothes at the “Downton Abbey” season premiere. It dates back to the Edwardian period circa 1903.

Charles Frederick Worth, considered the “father of couture,” was the most prominent couturiers in 19th-century Paris. The large bustle reflects a popular fashion of the latter 19th century, when horsehair pads or steel wiring supported voluminous skirts. The bodice was donated a few years before the skirt, which had been assumed lost. When pieces of the skirt bustle arrived, West immediately realized that the two went together. Following the original stitch lines of the skirt pieces, she reassembled the skirt and bustle, completing the ensemble.

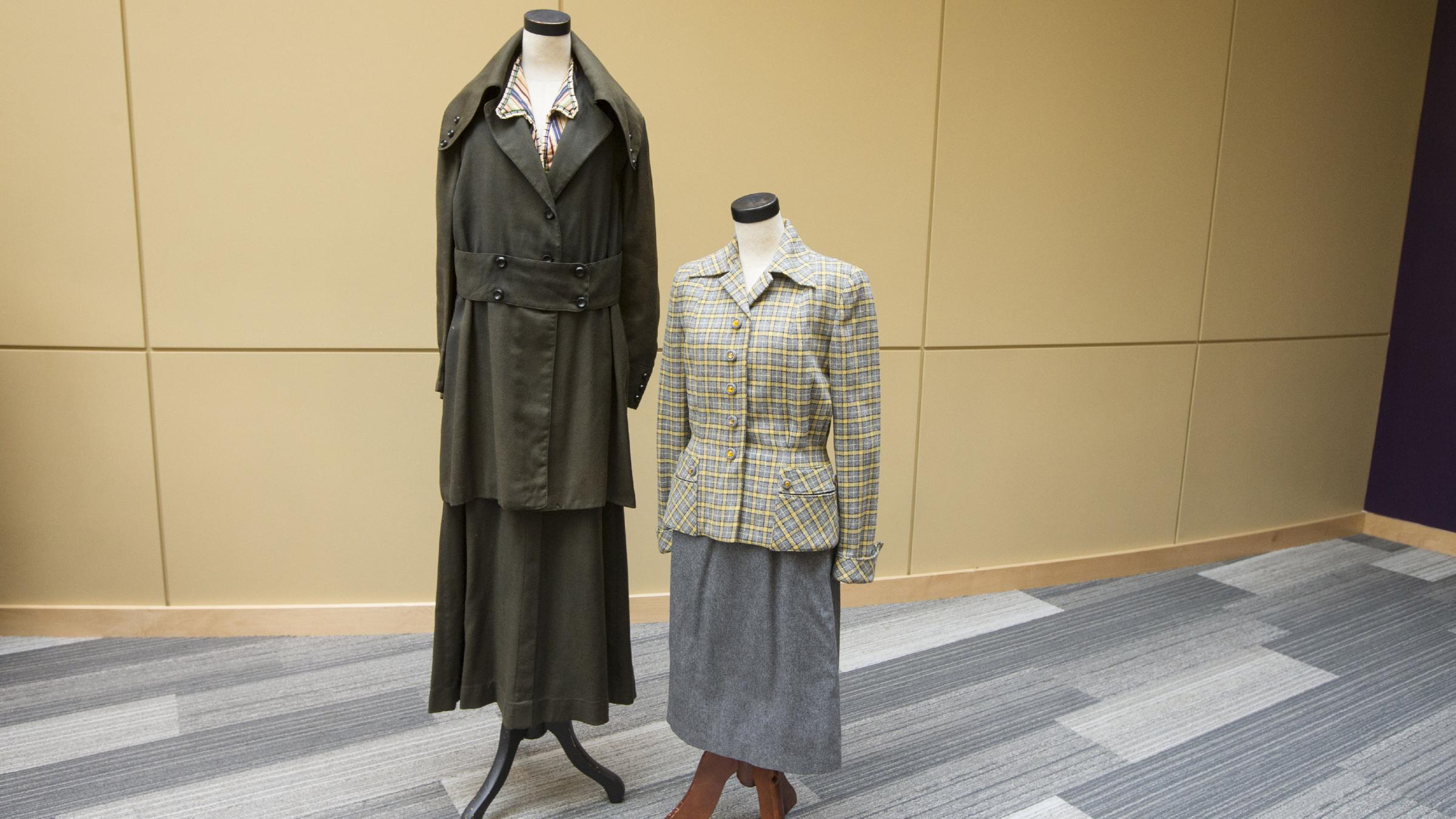

These suits hail from World Wars I and II, showing striking differences in women’s fashion during the two conflicts. The World War I-era suit at left is sturdy, practical and economical, with a boxy silhouette echoing uniforms worn by the women’s husbands, brothers and sons. It reflects the grim practicality and economic hardship of that watershed conflict, unprecedented in its mechanized destruction.

The suit at right hails from World War II, when the American economy was transitioning from the Great Depression to a boom period. The war was certainly frightening, especially after Pearl Harbor, but economic growth gave it a different energy than its predecessor, reflected in the brighter colors and patterns of women’s fashion.

The dress at left is a classic example of 1920s style, with a drop-waist silhouette in airy chiffon. It also shows hints of the bias-cut silhouette that would come into fashion in the 1930s. The owner likely wore the dress with a wide-brimmed hat and gloves to an afternoon event, such as a tea or garden party, West said.

Award-winning American designer Bill Blass, whose work became a hallmark of post-war American fashion, designed the evening dress at right, dated between 1969 and 1971. Its unusual quilted synthetic textile and bold pattern reflect the direction of American fashion at the time, giving it the iconic quality that West seeks when choosing which contemporary garments to preserve for future generations of students.

Caroline Newman

Media Relations Assistant

Office of University Communications

Original Publication – UVA Today

You are using an old version of Internet Explorer. Our site is developed with the latest technology, which is not supported by older browsers

We recommend that you use Google Chrome for accessing our (or any) website. It is a FREE and modern web-browser which supports the latest web technologies offering you a cleaner and more secure browsing experience.