UVA Teacher and Alumna Shares Process of Healing from Breast Cancer

While grinding out three months of chemotherapy for breast cancer, Charlotte Matthews spent a lot of the time doing what …

With a needle in her arm sending a toxic chemical to fight off cancer, Matthews – a poet and writing teacher in the University of Virginia’s Bachelor of Interdisciplinary Studies program – put down her thoughts and feelings, observations and memories in the notebook that she always carries with her. For many years, her notebook has served as a kind of laboratory for her creative writing, whether she’s mixing words for poems or prose.

Ten years after being diagnosed with stage III breast cancer at the age of 39, Matthews still brings her notebook wherever she goes and still advises her students to do the same. She found writing poetry so powerful in the healing process that she plans to share this aid with other cancer patients.

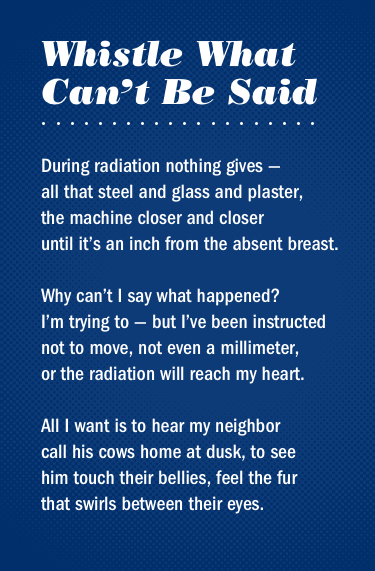

Her third book, “Whistle What Can’t Be Said,” has a section of poems chronicling her experience with cancer. She will give a reading, free and open to the public, of her work on March 23 at 7 p.m. in Zehmer Hall, the same day the book officially comes out.

“You take this journey to another land when going for treatments, and yet at the same time, you still have to live your life,” she said.

For Matthews, then a single mother, that meant caring for her two children – ages 7 and 4 when she was initially diagnosed – as well as keeping up a part-time job teaching writing and visiting the five centers each semester where UVA’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies offers the BIS program for nontraditional students. Most of the time, she also kept up as best she could her schedule for working on poetry and other personal writing from 4 a.m. to 6 a.m., before her children would wake up.

After going through a double mastectomy and chemo, having her ovaries removed and then getting radiation, Matthews, in remission, still takes medication and goes for check-ups every three months. “It’s a different way of living in the world,” she said.

Matthews, who earned her B.A. in English at UVA in 1988, is more committed than ever to creative expression – not only her own, but also helping others find their voice.

A friend suggested that sharing her poetry with others going through a similar experience could be helpful to them, too. While patients undergoing treatment and the medical personnel working with them get to know each other – “It gets to be like a family,” Matthews said – they don’t necessarily have a way to talk about everything.

“So much about the treatment is clinical. It’s hard work the medical people are doing. They have to be professional,” she said, “but they are simultaneously full of compassion and care.”

Matthews would like to open a conversation with others about what it’s like going through cancer treatment, to give people a way of talking about all the worries and fears they might have – the whole range of thoughts and feelings.

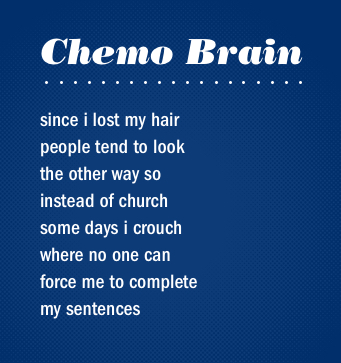

Poetry, through both reading and writing it, can be a springboard for discussion. She’d like to add it to the resources that cancer centers have, such as counseling support groups. Knowing some things have changed since her treatment, she recalled but no one talked much about what they were feeling inside, or about side-effects like “chemo brain” that makes one forget things and feel confused.

“We live so much of life on a mundane, superficial level,” she said. “Poetry deals with the state of being human, the problems of being human.”

For those who might feel intimidated about verse, she offered these suggestions: Poetry is “almost like overhearing someone talking.” One of her former teachers described it as “a human inside talking to another human inside.”

Even in her essay-writing courses, she begins each class with a poem and a writing exercise. Besides essay writing, she’s also teaching a course on “Memory and the Human Condition.” She chooses poems that are accessible; “I don’t want it to be a riddle. I want it to be a key,” she said.

Another way she tries to make poetry more approachable is by trading original poems for charitable donations. She has lugged a 1941 Corona portable typewriter to Charlottesville’s outdoor farm market, the Paramount Theater, the Crozet Arts & Crafts Festival and elsewhere. A person can request a poem about someone or something. Then she asks the customer to pick a few objects and words from the basket of selections she provides. She composes the poem on the spot in a few minutes.

Children love it, she said. When they’ve wanted to pay her, she would ask them to make her a drawing instead.

“You can order a taco. Why can’t you order a poem?,” she quipped.

In addition to writing poetry, Matthews has finished a novel, “Lost and Found,” that an agent has accepted about a 12-year-old boy with autism, and she’s working on a memoir, a segment of which was published by storySouth. She gained some writing time in spring 2014 when she held the Maxwell C. Weiner Distinguished Professorship of the Humanities at Missouri University of Science and Technology.

Matthews is the author of the poetry collections “Still Enough to Be Dreaming” and “Green Stars,” as well as “Whistle What Can’t Be Said.” Her work has appeared in the Virginia Quarterly Review, Borderlands, Ecotone, Tar River Poetry and storySouth. She received the 2007 New Writers Award from the Fellowship for Southern Writers. She earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from Warren Wilson College’s Program for Writers.

Her experience with cancer has given her a new scaffolding on which she continues to build her life, she said.

“The way I navigate the world is totally different now,” Matthews said. “As someone given the chance to live going beyond a certain prognosis, it’s a new chance at life.”

Anne E. Bromley

UVA Today Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication – UVA Today

You are using an old version of Internet Explorer. Our site is developed with the latest technology, which is not supported by older browsers

We recommend that you use Google Chrome for accessing our (or any) website. It is a FREE and modern web-browser which supports the latest web technologies offering you a cleaner and more secure browsing experience.