The Wooden ‘Delorme Dome’ Comes Home to Jefferson’s Academical Village

Near the end of the University of Virginia’s spring semester, Katie Watts had a choice between writing a final paper …

Near the end of the University of Virginia’s spring semester, Katie Watts had a choice between writing a final paper or undertaking 16 more hours of labor on the model of UVA’s original Rotunda dome that her class was completing.

To her own surprise, Watts – who earned her master’s degree in architectural history from the University in May – chose the 16 hours of construction work.

“As a historian, I was much more comfortable with the idea of writing a paper,” Watts said, noting that the closest thing she had to construction experience was building her Ikea furniture. “But I decided to go outside my comfort zone and work on the dome instead.”

Watts, together with 14 other graduate and undergraduate students in Benjamin Hays’ “History of American Building Technology” course, built a replica of the original wooden dome that perished when the Thomas Jefferson-designed Rotunda caught fire in 1895. It was replaced by a tile dome out of concern for future fires.

As UVA celebrates its bicentennial, visitors can now see what that original wooden dome would have looked like, thanks to more than 400 hours of work by Hays’ students, aided by several outside architects and builders.

The model dome, which will be on display on the Lawn until the end of June, was created with support from UVA’s Bicentennial Commission and Castleton Farms in Rappahannock County. At one-third the scale of the real Rotunda dome, it’s an imposing structure and a tangible reminder of founder Thomas Jefferson’s vision of the University 200 years ago.

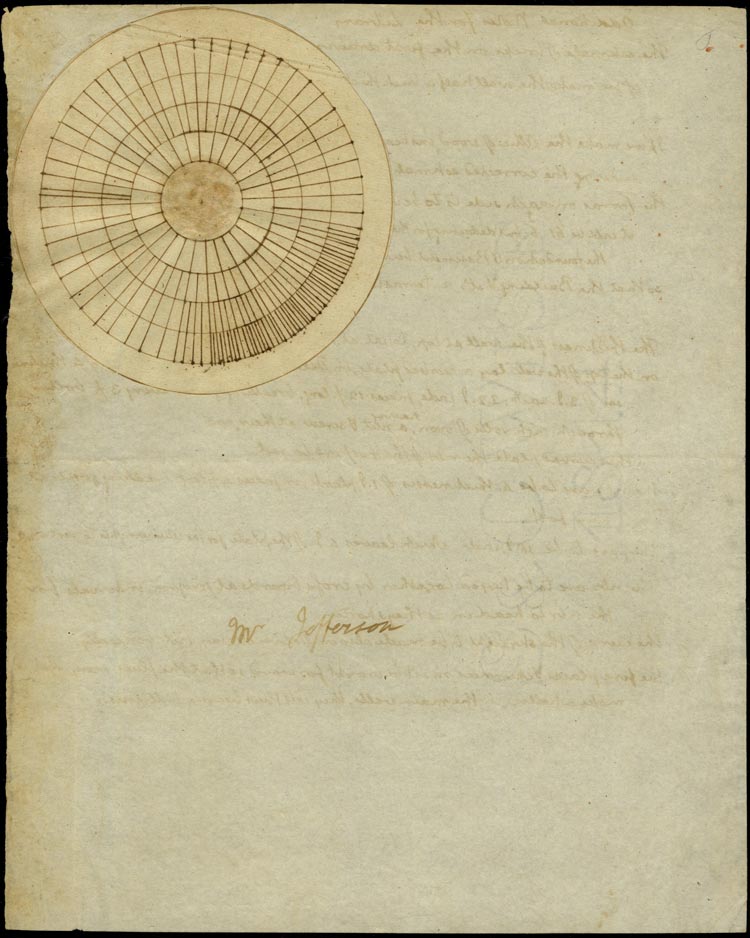

Hays used Jefferson’s own drawings and notes as the basis for the model his class built. (Image: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

Hays used Jefferson’s own drawings and notes as the basis for the model his class built. (Image: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

“Everything is to scale and the structure is true to Jefferson’s original specifications,” said Hays, a lecturer in the School of Architecture and the University Building Official. “It’s thrilling to be able to tell that story in a very visible way, and to show people what it would have looked like.”

Jefferson’s designs for the original dome were inspired by the work of 16th-century French architect Philibert Delorme, who pioneered the technique of using wooden ribs to create beautiful and sturdy domes. UVA’s future founder learned of Delorme in 1786 while serving as the American ambassador to France. His friend Maria Cosway took him on a tour of Paris that included the Halle aux blés, an indoor marketplace capped by an impressive Delorme-style wooden dome.

Captivated, Jefferson bought Delorme’s handbook and eventually had America’s first Delorme dome installed at Monticello in 1801. The Rotunda dome followed in 1824. It was about 75 feet wide and made of wide 16- to 18-inch oak beams intersected by numerous smaller pieces, all held together with long iron nails manufactured at Monticello.

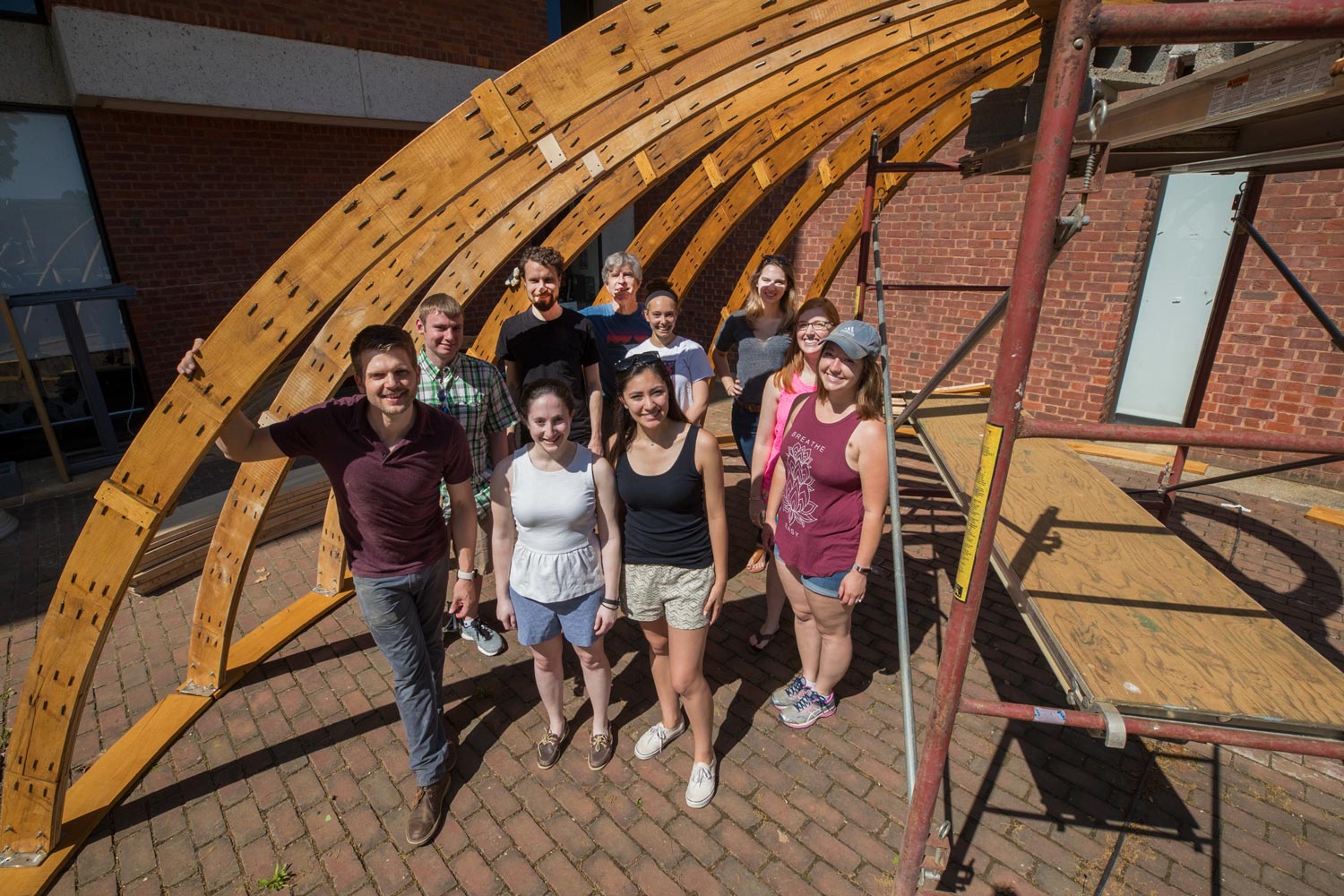

Hays and architect Douglas Harnsberger, who has spent much of his career studying Delorme’s work, used Jefferson’s original notes, housed in UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, to plan their model. The result is a 25-foot wide structure composed of more than 1,100 pieces of white oak carefully fitted together using historically accurate nails similar to those in the original dome. Hays, far left, and his students assembled the model outside of Campbell Hall throughout the semester. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Hays, far left, and his students assembled the model outside of Campbell Hall throughout the semester. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Though this was the largest model Hays had built, it was not the first time he had built a Delorme dome. He led students in another modeling project two years ago, building smaller-scale models of both the wooden Delorme dome and of the tiled dome installed after the fire, which was designed by Spanish-American architect Rafael Guastavino.

Hays returned to the modeling project because creating the historic structures helped students understand the underpinnings of modern building technology.

“One of my biggest pedagogical beliefs is that we don’t just learn through lectures or readings,” Hays said. “Significant insight can come by actually building something.”

His students learned not only about the craft of building, but about the craftsmen – many of them enslaved laborers – who built the original Rotunda dome.

“My favorite part of the project was stepping into the craftsman’s shoes,” second-year architectural history graduate student Tabitha Sabky said. “Working with my hands and engaging with history through physical materials allowed me to approach the history of building construction not through the designer’s perspective, but through the everyday worker’s perspective. Each issue that we faced forced us to step into the mindset of a Jefferson-era craftsman and learn the processes of workers who have been largely ignored in the architectural history narratives.”

Students said they loved the hands-on nature of the project and learned a lot from the day-to-day problem-solving it required. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Students said they loved the hands-on nature of the project and learned a lot from the day-to-day problem-solving it required. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The class spent a lot of time troubleshooting at first, but eventually, she said, they got the hang of it.

“One of my favorite parts of the project was seeing the progress we made as a group from the first day we tried to assemble the ribs to the next weekend, when we could quickly get a rib together in about 30 minutes,” Watts said.

“With any construction project, there are issues that force you to adapt,” Sabky said. “However, it was these issues that were the most instructive, because they allowed for creative thought and ingenuity.”

Though the project took longer than expected, a few students stayed in Charlottesville to finish it with Hays and Harnsberger in the weeks after graduation. On Tuesday, they moved everything to the Lawn to assemble the final dome there.

The model will be on display on the Lawn through the end of the month. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The model will be on display on the Lawn through the end of the month. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Now, it stands as a reminder of both Jefferson’s original design for the Rotunda and his expansive influence on American architecture. After Jefferson used Delorme domes at Monticello and UVA, more and more of them began cropping up along the East Coast.

“Jefferson’s promotion of Delorme’s dome went far beyond Charlottesville in impacting the fledgling American neoclassical architecture tradition,” Harnsberger wrote in a summary of the model.

His evangelism of Delorme’s method contributed to the first Delorme domes at the U.S. Capitol, the Baltimore Cathedral, the Monumental Church in Richmond, the Faneuil Hall Marketplace in Boston and several more.

“It is no understatement to say that Jefferson’s fascination with the Delorme dome at the Halle aux blés grain market in Paris resulted in the creation of the first American neoclassical domes,” Harnsberger said.

In late June, the dome will travel to Castleton Farms, where it will be displayed throughout the rest of the summer.

Caroline Newman

Senior Writer and Assistant Editor of Illimitable

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today

You are using an old version of Internet Explorer. Our site is developed with the latest technology, which is not supported by older browsers

We recommend that you use Google Chrome for accessing our (or any) website. It is a FREE and modern web-browser which supports the latest web technologies offering you a cleaner and more secure browsing experience.