Take a Journey Through Pompeii with Photography Professor William Wylie

Each time University of Virginia photography professor William Wylie returns to Pompeii, he finds something new to awe, humble or …

Each time University of Virginia photography professor William Wylie returns to Pompeii, he finds something new to awe, humble or inspire him.

For Wylie, a trip to the ill-fated Roman city is a journey through time. It reflects not only the catastrophic volcanic eruption in 79 AD that destroyed the Roman city and killed about 2,000 of its inhabitants, but also the archeologists and artists who have slowly pieced the remains of the city together, and the tourists – 2.5 million of them each year – who witness the devastation afresh each day.

“For me, much of the mystery of Pompeii lies in the site’s layers. Archeologists work by uncovering and studying the deposits of past eras, but even visitors experience the site in this way,” Wylie said. “I was motivated to try and make photographs that revealed some of Pompeii’s complexity, the way multiple pasts intersect there with our 21st-century present.”

In more than 100 photographs taken over the course of five years, Wylie captures Pompeii’s erstwhile beauty, its breathtaking tragedy and its ongoing history as an archeological site. Eighteen of those photographs are currently on display at the Yale University Art Gallery. A major exhibition of the work recently closed at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art at Colorado State University and will travel to Vanderbilt University and the Fralin Museum of Art at UVA over the next year.

The photographs in that exhibition, along with 50 other images of Pompeii, and are featured in Wylie’s new book, “Pompeii Archive,” recently published by Yale University Press.

Below, Wylie shares a few of his favorite images and the stories behind them.

Photos by William Wylie

Photos by William Wylie

Wylie’s photos are inspired in part by the work of Giorgio Sommer, a mid-19th-century German photographer who documented parts of Pompeii’s excavation. Wylie liked how the photographer created layers in his composition that evoked the layers of history being uncovered on site.

This photo, Wylie said, uses a similar technique with a layered composition showing Mount Vesuvius, Pompeii’s ruined Basilica and the glassy plane of floodwater that invaded the site the day Wylie took the photo.

“Vesuvius is always looming above the city site, reminding the visitor why these ruins exist. In this photograph the mountain is squeezed into the flatness of the scene, like a collage, which is further activated by the flooded space of the Basilica on that day.”

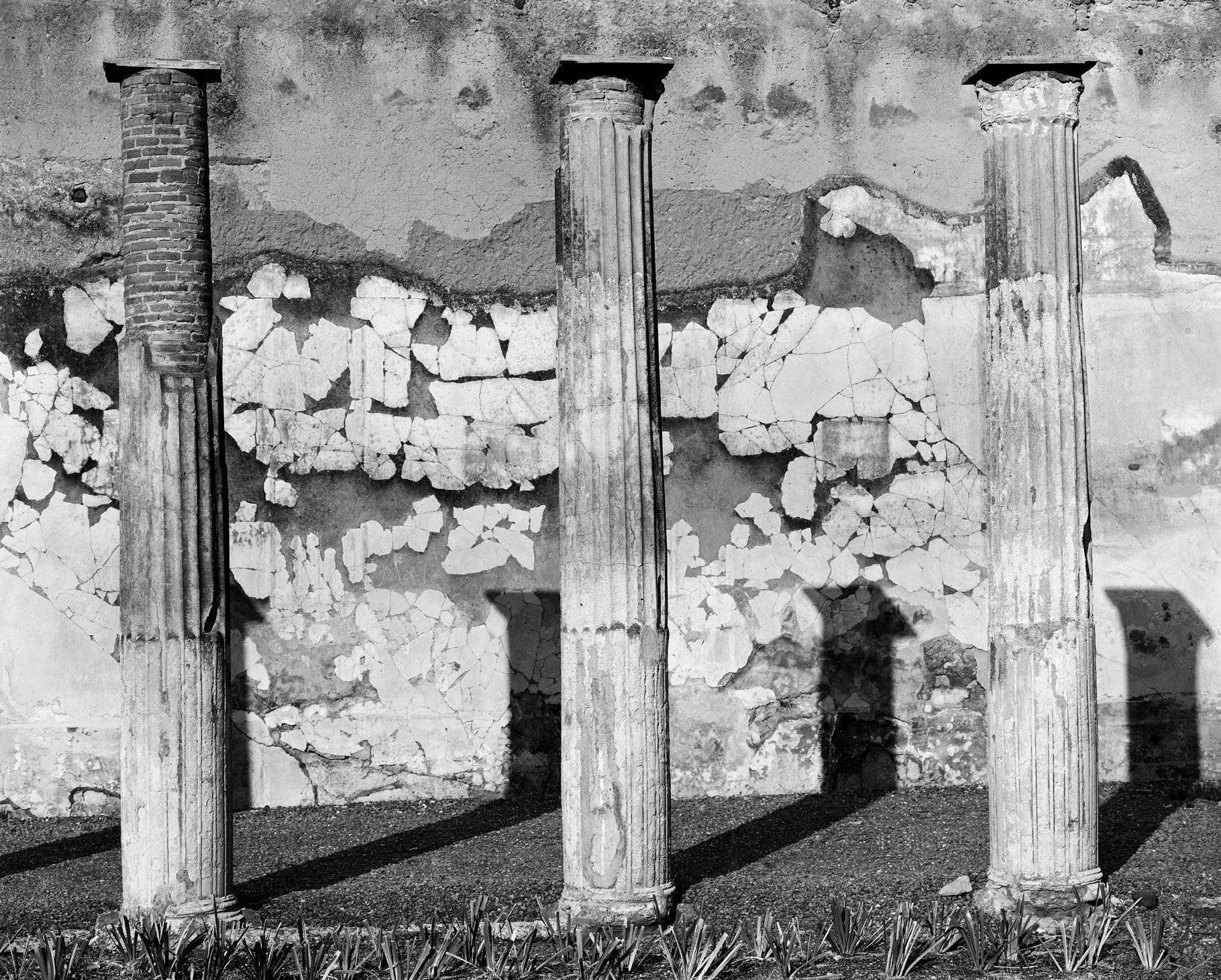

This photo shows a peristyle, which in Greek and Roman architecture typically means an open courtyard surrounded by a columned porch.

“This is a somewhat commonplace scene at Pompeii. A row of columns stands along the edge of a garden space, supporting nothing but what [German philosopher Martin] Heidegger has referred to as ‘the invisible air’ of space. The four shadows give a shallow depth and a strange isometric perspective to that amazing wall, repaired with fragments, but perfect in its spatial ambiguity.”

“The gardeners had recently chopped the tops off the sedges and I liked how they resembled the columns and the weird flame-like stains on the upper wall.”

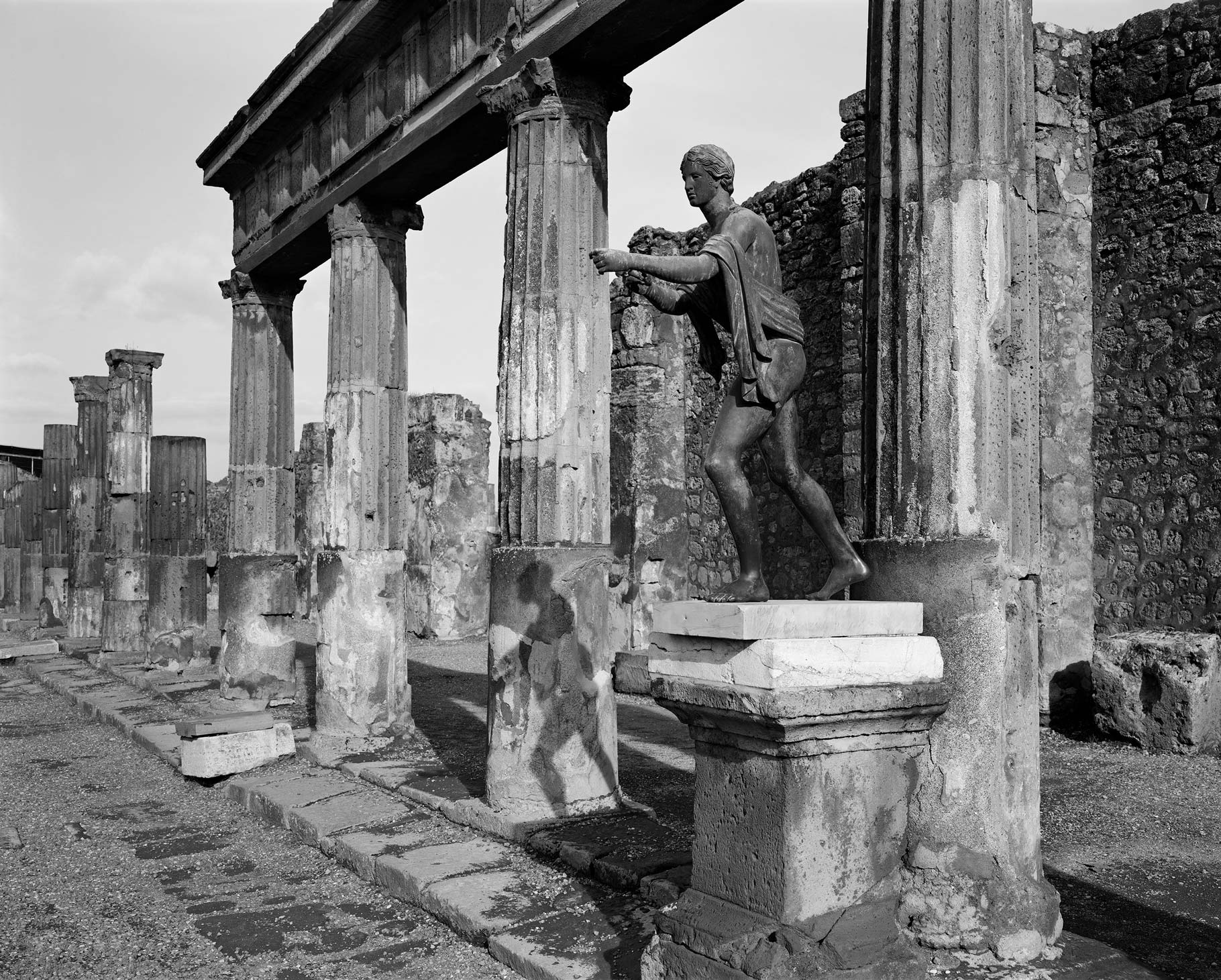

Wylie said this photo of the Temple of Apollo felt particularly extraordinary because it reflected one of Sommer’s 19th-century compositions while adding a new element – the Apollo statue that was restored in 2009 and returned to its original site.

“It’s an old idea, but you still cannot escape the importance of time, or the precise moment, in photography. This photograph has an interesting compression of time involved in its making and its unseen life in the world.

“I began my work in Pompeii with a fairly extensive knowledge of the photographs made there in the 19th century by the Grand Tour photographer Giorgio Sommer. I likely stood on the exact spot he had when I made this image because there are versions in his oeuvre that are very close. But the statue of Apollo was not present in Sommer’s views. It was only later that the scattered fragments of the original bronze statue were assembled and determined to have been located on that pedestal. I was surrounded by the ruins of the ancient world and an attempt to reconstruct at least part of what had been lost, and yet I was also thinking of a specific 19th-century image of that place. Then that shadow, projected on the column base, locked me into the present in a way few photographic experiences have for me.”

“This photograph was made in a race against the dying light of the day. A sense of compression is always present in the walls of Pompeii, and this relief facing the courtyard in the Stabian Baths had deteriorated to a sort of perfection in my mind. All the details are present within a beautiful flux of visibility and invisibility depending on the time of day and the amount of light strafing the wall.

“I’d walked by this wall and checked the conditions dozens of times over the years before this moment happened. The winter sun was very quickly disappearing in the late afternoon and the light hit only the peak relief features. Ghost figures moved through architectural forms that almost popped off the wall. The rougher stone under the plaster relief, visible at the top and bottom of the photograph, suggested the history of Pompeii itself, a city frozen and buried under the volcanic matter.”

Looking back at this photo, Wylie unearthed a comparison that made it feel even more powerful.

“These columns are laid out like the fallen soldiers in old Civil War photographs, side by side, opposite end to opposite end. Behind their bodies, their damaged and scarred brick companions form a tattered line. In the photograph, there is a quietude that feels like an aftermath.

“None of that was in my mind when I made the exposure. I only recall the perfection of the form and the rolling rhythm of the top of the wall against that clear sky. I also remember the warm winter sun on my back, and my family excitedly talking nearby about some broken pottery fragments.

“[French philosopher] Roland Barthes talks about the photographer’s ‘second sight,’ shooting at the right moment, and creating what he referred to as the ‘punctum.’ Punctums are not intentionally put there by the photographer. The punctum is what Barthes describes as the thing that ‘pricks or bruises.’ It’s detail that makes the viewer feel something and pushes you even further into the photo.”

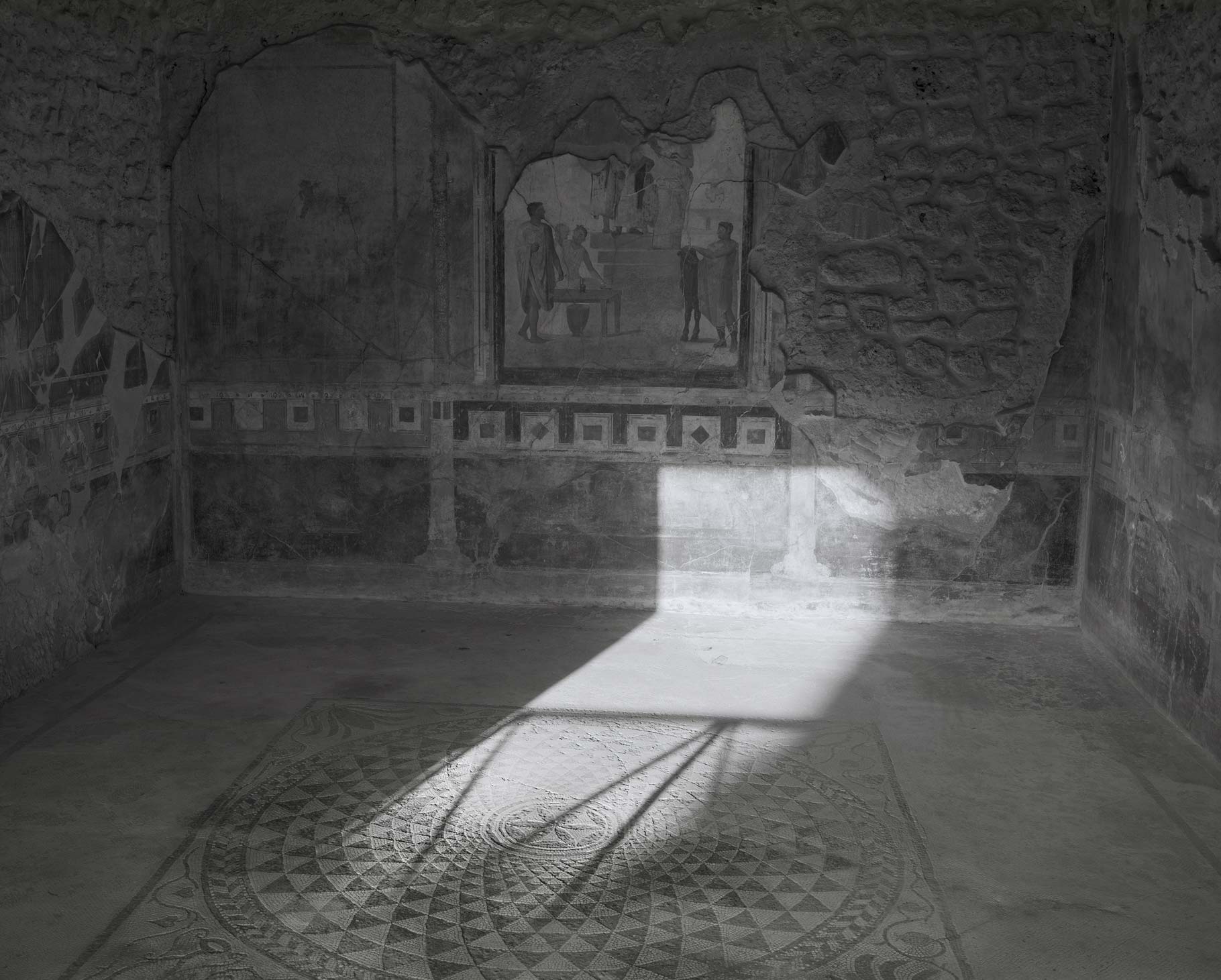

This home was among the more sumptuous in the ancient city, belonging to the Poppei family. It is named for the gold-leaf Cupids depicted among its many frescos.

“Sometimes the daily opulence of ancient Pompeii just comes to life. In the right afternoon light, this beautiful mosaic and the rich fresco paintings on the walls of the room create a sense of lived experience that is almost palpable. And this kind of experience is what makes Pompeii such an incredible place. Buried and preserved and then uncovered and revealed, time seems stopped. But another look reveals the cracked edges and crumbling plaster and an unclear transaction between some men and what looks to be a horse.

“It’s like a dark memory. Whatever is going on, it doesn’t feel like it is going to end well.”

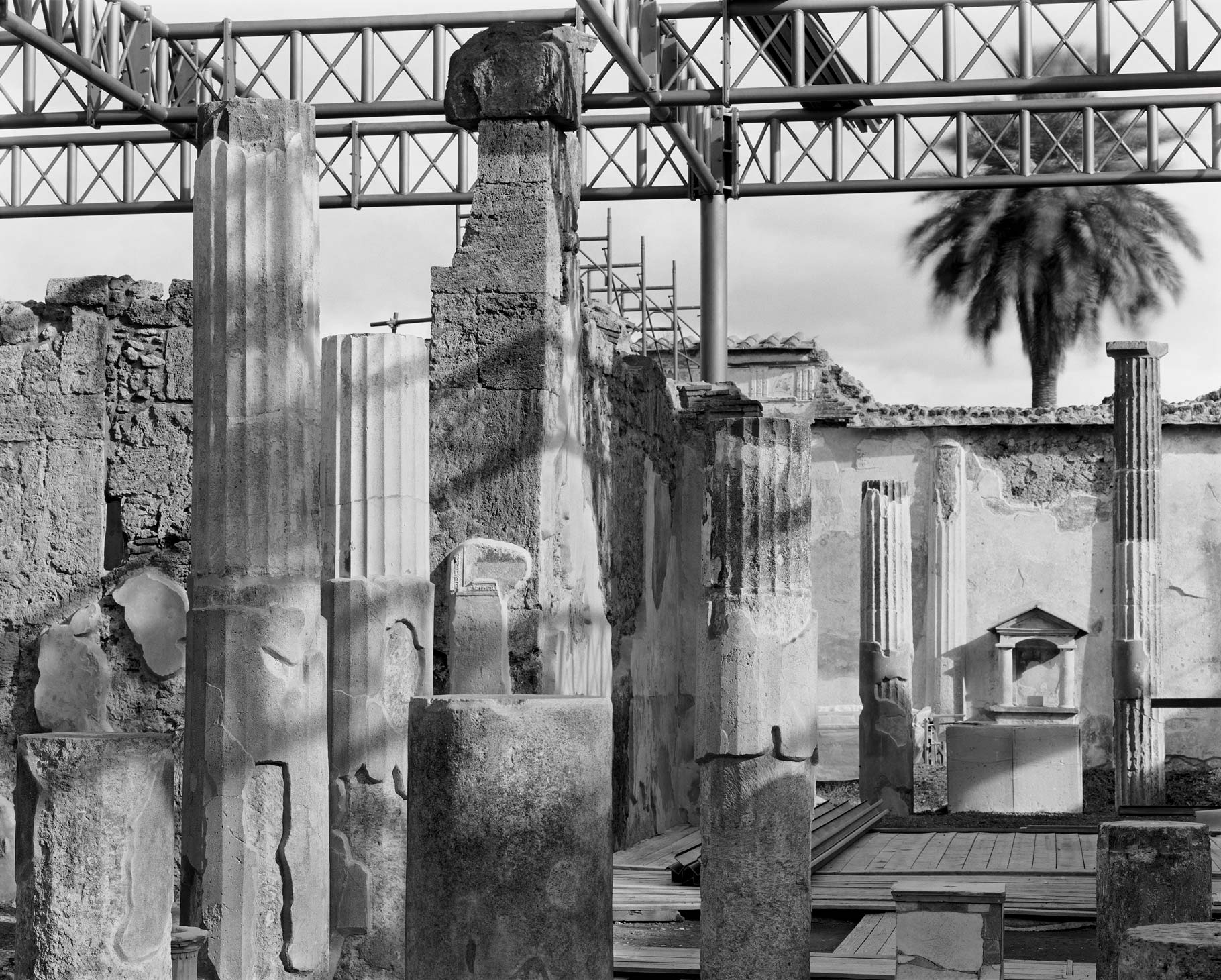

The modern and the ancient intersect in this photo, as Wylie captured both the house itself and the preservation efforts underway.

“This photograph makes me think of a movie set with the props and tracks for lights.

“On this day I couldn’t find someone to let me in to the House of Dioscuri. But I really wanted to make an exposure because the light was perfect, and the scene was so clear in my mind. I had to stick my lens through the space between the bars of the gate and I didn’t have much freedom to move around or change the composition. I liked the way the frame was broken up into zones, with the overlapping columns all jumbled in the lower left and the space opening up on the right. That palm tree is the only organic form there and is such a column-like shape. The long exposure was unpredictable but produced a distinct sense of time extended within the frozen moment of the still photograph.”

The last image Wylie chose to share is a poignant reminder of the lives cut short by Mount Vesuvius so many years ago. It shows the cast of a child’s body, one member of a family of four that died that day, buried while hiding in their home.

Sadly, Wylie said, it’s a scene he can still imagine in war-torn or disaster-ravaged areas of the world today.

“This figure, in a position preserved at the moment of death, was made by archaeologists in the 19th century using Giuseppe Fiorelli’s technique of pouring liquid plaster into the hollows left in the ash where bodies had decomposed.

“When I was let into the House of the Golden Bracelet, I did not know that the child was part of a family group. This was a scene I could have imagined out of Aleppo or some other wartorn city, where the wounded or dead were laid out in makeshift triage beds. The other ‘beds’ were empty and this figure seemed to be floating away.”

Caroline Newman

Senior Writer and Assistant Editor of Illimitable

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today

You are using an old version of Internet Explorer. Our site is developed with the latest technology, which is not supported by older browsers

We recommend that you use Google Chrome for accessing our (or any) website. It is a FREE and modern web-browser which supports the latest web technologies offering you a cleaner and more secure browsing experience.