Exhibit Celebrates Black Sisterhood Through the Centuries

From family photos to soul groups’ album covers, a new exhibit in the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small …

From family photos to soul groups’ album covers, a new exhibit in the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library pays tribute to the powerful stories of African American women – from their daily lives, alone and together, to groundbreaking successes, locally and on the national stage.

Combing through the library’s manuscript collections and University Archives, staff members Ervin Jordan, Regina Rush and Sony Prosper brought together 70 photos, documents and artifacts in honor of Black History Month and last year’s 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first Africans to what would become Virginia.

The exhibit, located in the two long cases on the walls outside the Rare Book Room in the Harrison/Small building, will be on display until June 13.

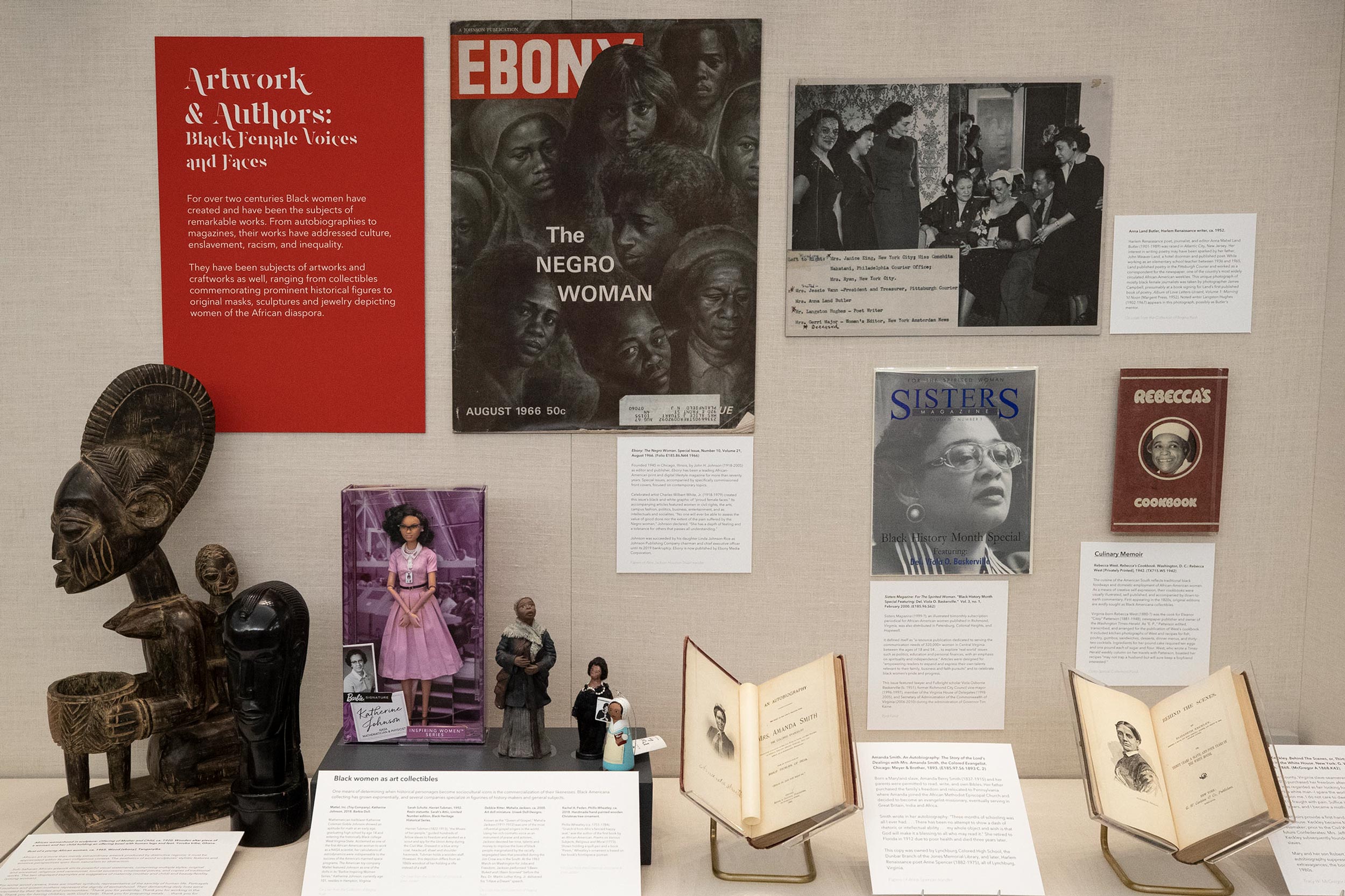

Jordan, an associate professor and research archivist, along with Rush, a reference librarian, and Prosper, resident librarian, organized the exhibit around five themes: “Black UVA Women: Being First,” “Charlottesville-Albemarle Women: Groundbreakers on the Homefront,” “Artwork & Authors: Black Female Voices and Faces,” “Fashions & Livelihoods: The Way They Wore” and “Love, Marriage & Family: The Ties that Bind.”

The “Sisterhood” exhibit, on display until June 13, includes photos, documents and artifacts of African American women in honor of Black History Month.

Jordan said working on the exhibit had been a learning experience for him even though he has worked in Special Collections for 40 years.

For example, he pointed to a couple of unique items in the exhibit: an order form for a wedding outfit complete with gloves and veil that a woman named Hopie Wright ordered from a Chicago firm’s catalog in 1914; and a facsimile of an old photo, circa the 1890s, in which a group of black tourists posed when they visited Gettysburg Battlefield.

This is a facsimile of an album in print circa 1890s of a group of black tourists visiting Gettysburg Battlefield.

This is a facsimile of an album in print circa 1890s of a group of black tourists visiting Gettysburg Battlefield.

“Over the past 40 to 50 years, there’s been a movement by libraries of big institutions to include more stories of members of marginalized groups,” said Prosper, who is one of two inaugural resident librarians who came to UVA Library in 2018 as part of the Diversity Alliance that comprises more than 40 academic libraries.

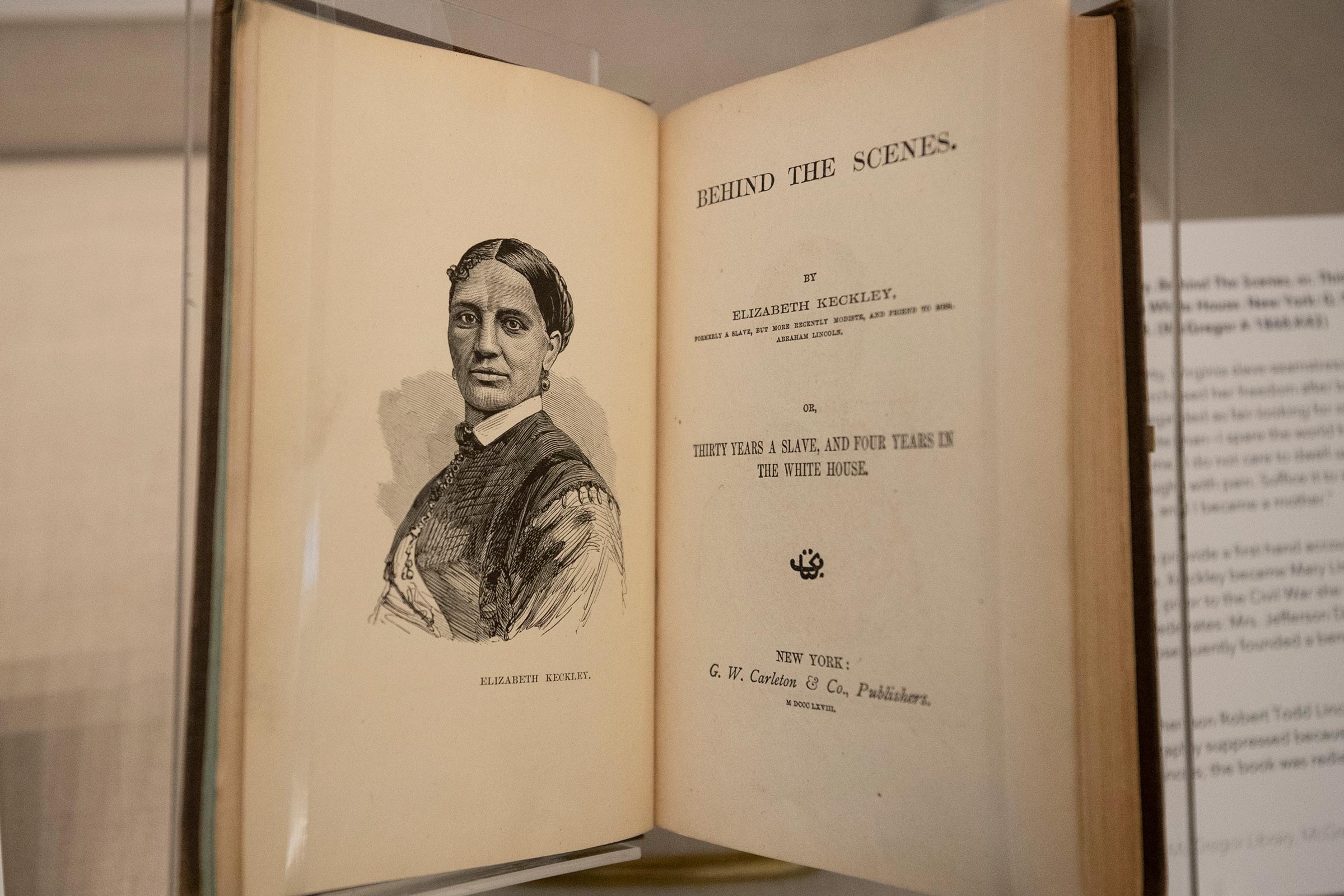

Another one of the older items is a copy of the Elizabeth Keckley’s 1868 book, “Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House.” Keckley, an enslaved Virginia seamstress who bought her freedom, later worked as “modiste” or dressmaker, for Mary Todd Lincoln when she became first lady, and the two became friends.

Elizabeth Keckley, an enslaved seamstress who bought her freedom and later became Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker, published her memoir in 1868.

Elizabeth Keckley, an enslaved seamstress who bought her freedom and later became Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker, published her memoir in 1868.

Both a slave narrative and a portrait of the Lincolns, Keckley published it in part to help Mary Todd Lincoln, who had financial strains after her husband’s assassination, but the book led to public disapproval for revealing many personal details about the White House couple.

Ironically, among Keckley’s earlier elite clientele were Varina Davis, wife of Confederate States of America President Jefferson Davis, and Mary Anna Custis Lee, wife of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, Jordan said.

For the exhibit’s section on fashions and livelihoods, Prosper chose a collage of images from the Holsinger Studio Collection, which includes almost 500 portraits of African American residents from the area. Most of the Prosper’s selections show two or three women – emphasizing their sisterhood.

“During the early 20th century, numerous black women sat for photographs which show the ways in which they chose to define, envision and imagine themselves,” Prosper wrote for the exhibit. Although there is often a name attached to a photo, it doesn’t seem to correspond to the individuals in the portraits, so many people have remained anonymous. Others at UVA have reached out to local residents to see if they can identify anyone.

Small groups of black women from the area commissioned photos from Rufus W. Holsinger, a prolific local photographer who worked for about 50 years in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Small groups of black women from the area commissioned photos from Rufus W. Holsinger, a prolific local photographer who worked for about 50 years in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“So it is left to [black women] to envision things otherwise; as exhausted as they are, they don’t relent, they try to make a way out of no way, to not be defeated by defeat,” wrote literary scholar and cultural historian Saidiya Hartman in her 2019 book, “Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiences: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval,” that Prosper quotes in his description of a collage that features photos by Rufus W. Holsinger in the early 20th century.

“While we don’t know what prompted these specific black women to have their photographs taken, we do know they each had ‘a name and a life that exceeded the frame in which [they] were captured,’” Prosper wrote.

The same can be said for a photo that Rush loaned to the exhibit: it shows her great-aunt, Mary Ann Rush, who grew up in Esmont and worked in Richmond. “Unfortunately, besides this photo taken some time during the 1920s, little information has survived that tells the story of her life,” Rush wrote in describing the photo.

Mary Ann Rush, depicted here, dressed like a quintessential “flapper girl” of the 1920s, “evidently knew a lot about fashion,” wrote reference librarian Regina Rush of her great-aunt.

Mary Ann Rush, depicted here, dressed like a quintessential “flapper girl” of the 1920s, “evidently knew a lot about fashion,” wrote reference librarian Regina Rush of her great-aunt.

“From the moment my cousin showed me the photograph years ago, I fell in love with it,” Rush said. “There is such a timelessness about it. The exact date the photograph was taken is not known, but based on her outfit it was probably sometime in the 1920s. I love that the photographer skillfully captured her sense of presence. Viewing the photograph today, close to 100 years later, you still sense it.”

Other local women whose successes are noted include civil rights activist and educator Florence Bryant, the only African American teacher in the Charlottesville school system when it was integrated in 1965; and Nikuyah Walker, who in 2018 became the first female African American mayor of Charlottesville.

The section on black women at UVA focuses on those who broke barriers in becoming firsts, such as Elizabeth Johnson, the first full-time admissions officer; and Charlotte Scott, the first tenured female African American professor (alongside her husband, Nathan Scott, in religious studies). Charlotte Scott served on the Darden School faculty and as University Professor of Commerce and Education at the Curry School of Education, retiring in 1998.

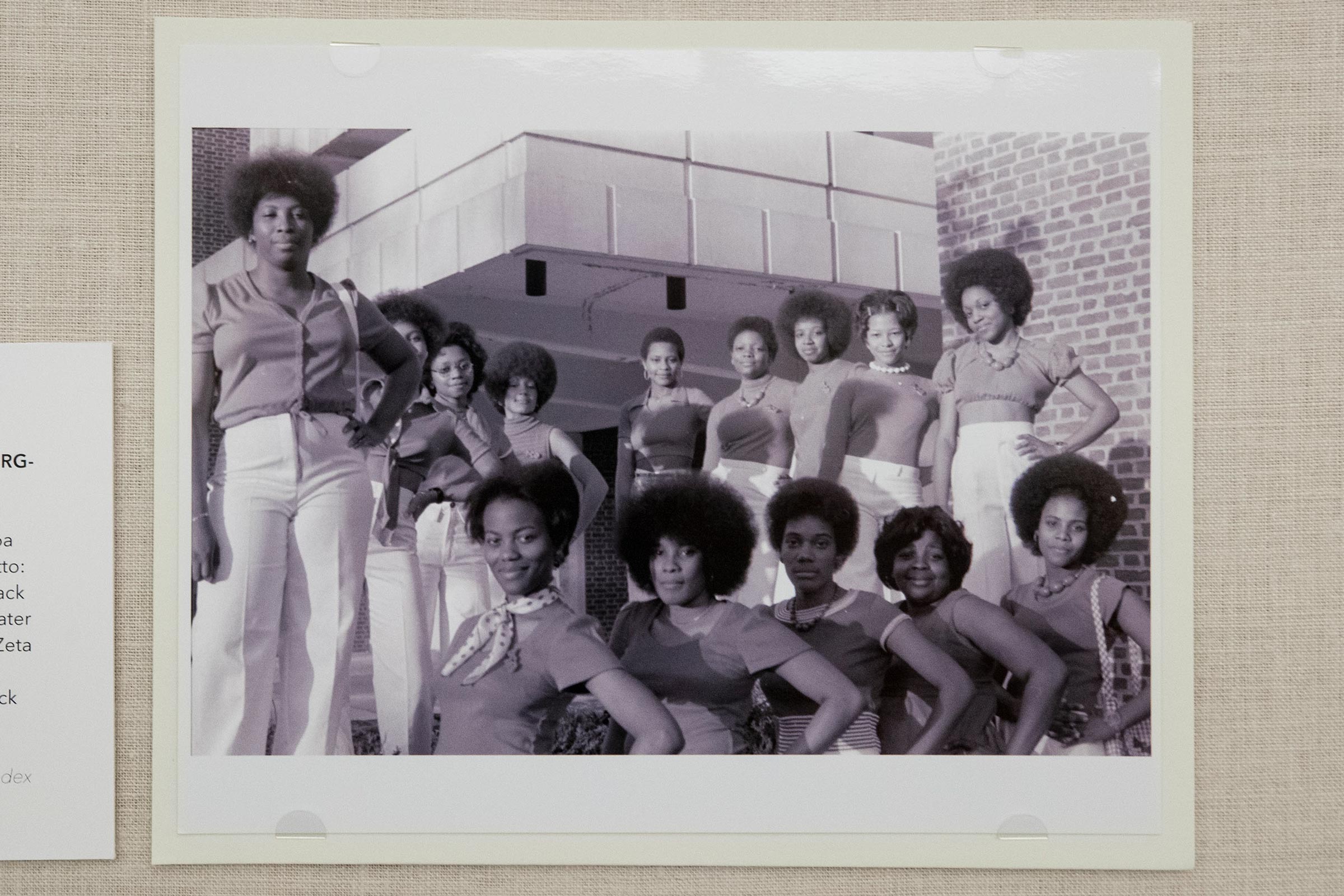

The first black sorority at UVA was the Kappa Rho chapter of Delta Sigma Theta, chartered in 1973.

The first black sorority at UVA was the Kappa Rho chapter of Delta Sigma Theta, chartered in 1973.

UVA’s chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority describes itself as continuing “to strengthen the University of Virginia community by achieving excellence through love for self, service, scholarship, and true sisterhood.”

Another display focusing on black female voices and portrayals shows an enlarged reproduction of the cover of a 1966 issue of Ebony magazine dedicated to black women under the title, “The Negro Woman.” Looking closely, the subscription mailing address indicates the magazine comes from the papers of Alice Jackson Houston Stuart, who in 1935 was the first African American to apply to UVA. Even though she was denied admission because of her race, after her death in 2001, her son, Julian T. Houston, a judge in Massachusetts, donated her papers to the University. The UVA section also includes a photo of a young Alice Jackson.

Among the images of black women, curators Ervin Jordan and Regina Rush loaned some of their own collectible items, from African sculptures to ornamental dolls.

Among the images of black women, curators Ervin Jordan and Regina Rush loaned some of their own collectible items, from African sculptures to ornamental dolls.

In a display of collectible items, one on loan from Rush is a Barbie version of Katherine Johnson, whose work with NASA features in UVA alumna Margot Lee Shetterly’s book, “Hidden Figures,” which also became a popular film in 2017.

Another photo in this section that belongs to Rush shows the writer Anna Land Butler, surrounded by other African American women who were journalists and editors in the 1950s, along with poet Langston Hughes. Butler, who was part of the Harlem Renaissance earlier in the 20th century, is signing one of her books.

Rush said the photo appealed to her for several reasons, among them, “I included the photograph in the exhibition because I wanted to pay homage to women such as these who paved the way for future black female journalists.”

Anne E. Bromley

University News Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today

You are using an old version of Internet Explorer. Our site is developed with the latest technology, which is not supported by older browsers

We recommend that you use Google Chrome for accessing our (or any) website. It is a FREE and modern web-browser which supports the latest web technologies offering you a cleaner and more secure browsing experience.