Alumna’s Research Guided Fiery Lyrics and Duels of Broadway Hit ‘Hamilton’

When University of Virginia alumna and renowned historian Joanne Freeman first took an interest in one of America’s lower-profile Founding …

It was a surprise and a thrill, then, to see how her research helped guide Lin-Manuel Miranda as he wrote a smash-hit musical about Alexander Hamilton, Freeman said.

Freeman, a professor of history and American studies at Yale University, has been studying Hamilton for more than 40 years. She is also a leading expert on early American politics, earning her master’s and Ph.D. at UVA. She studied under Peter Onuf, UVA’s Thomas Jefferson Professor of History Emeritus and one of the founding co-hosts of “BackStory,” the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities’ popular history podcast.

Freeman’s research on Alexander Hamilton made its way into the Broadway musical “Hamilton” after a mutual friend connected her with one of the show’s creators.

Freeman’s research on Alexander Hamilton made its way into the Broadway musical “Hamilton” after a mutual friend connected her with one of the show’s creators.

Freeman has now come full circle to join “BackStory” as one of two new permanent co-hosts while Onuf takes a more occasional role. In addition to her teaching and research at Yale, she will now join the “BackStory” crew once a week as they explore connections – and disconnections – between past and present.

Before her first episode as co-host airs on Friday, UVA Today sat down with Freeman to discuss her plans for the show and how her research became a part of the hottest ticket on Broadway.

Q. What are you most looking forward to about joining the permanent “BackStory” team?

A. We’re living in times when history really matters – when it’s a good thing to know where we’ve been as a nation, so we can help to shape our future. So being a part of the “BackStory” team at this moment has real importance. Of course, as a historian, I think that an awareness of history always matters. But given current events, it’s wonderful to have a public venue to talk about not just politics, but also social and cultural trends and shifting ideas about the meaning and realities of American nationhood.

It’s also wonderful to work with the team of people at “BackStory,” in front of the microphone and behind it. They’re amazing! On a purely selfish level, I really enjoy working with them.

Q. As you watch the news and plan for future episodes, what historical moments are at the forefront of your mind?

A. The one that’s foremost is the 1850s, a period that I’ve been writing about recently as I complete my next book [”The Field of Blood: Congressional Violence and the Road to Civil War,” Farrar, Straus Giroux]. That period comes to mind not only because it was extremely polarized, but because of the nature of that polarization. By the late 1850s, there were two groups of Americans with opposing ideas, each group assuming that the other was un-American and violating fundamental American ideals. Of course, the issue at hand was the problem of slavery, an issue where there wasn’t much of a middle ground.

Our current polarization, and the inability of each side to engage with the other, reminds me of the extreme polarization of the 1850s in many ways. But our political system is built on debate and compromise. That’s the foundation of our democracy. So at present, we’re at a moment of extreme political malfunction.

As an early American political historian, I’ve spent decades researching and writing about the creation of our political system. That kind of knowledge really matters right now. To get past our current political problems – to protect American democracy – people need to understand how our political system was created and structured, and how ideas about a democratic politics evolved over time.

Q. How did your research become a part of the hit musical “Hamilton”?

A. I heard word that someone out there was working on a play about Hamilton. I knew that it was based on a biography and – given that I assumed that in my lifetime there probably wouldn’t be a second musical about Alexander Hamilton – I very much wanted Hamilton’s own words to be in the show.

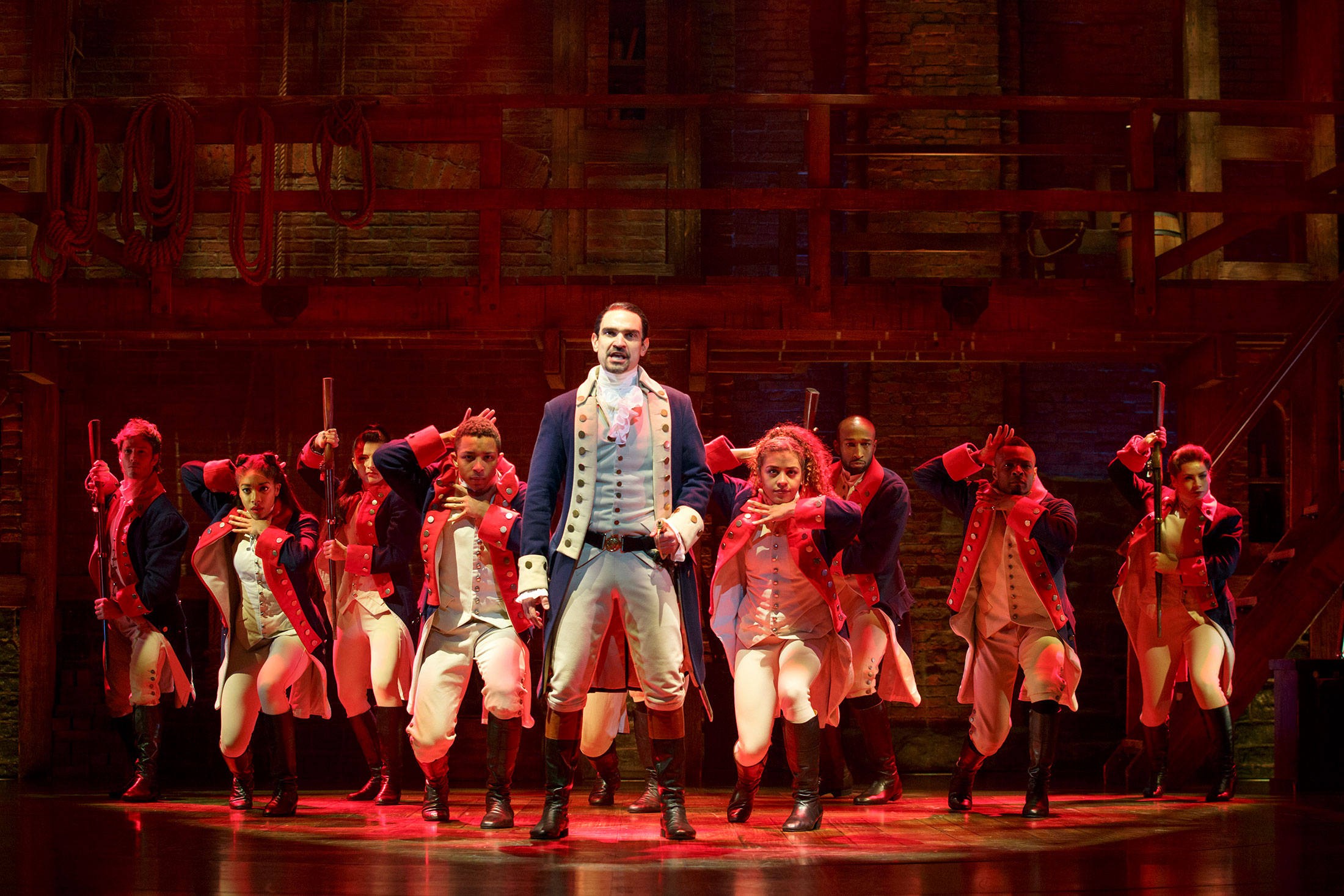

Javier Muñoz sings on stage as Hamilton’s title character. (Photo by Joan Marcus, courtesy of Hamilton).

Javier Muñoz sings on stage as Hamilton’s title character. (Photo by Joan Marcus, courtesy of Hamilton).

A friend of mine contacted Lin-Manuel Miranda through Twitter to let him know that I wanted to give him a copy of my edited book of Hamilton’s letters [“Alexander Hamilton: Writings”]. I eventually managed to meet Lin, gave him my book and urged him to put Hamilton’s words in the show.

Then I forgot about the play and years passed. When it opened, I was first in line to get tickets. And in watching the show, I noticed a song, “The Ten Duel Commandments,” that seemed to be based on part of my other book, a study of early American political combat [“Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic”]. As the song continued, I thought, “Wait, a minute, I know those words. They’re singing about archival documents that I found!”

The next time that I met Lin, I asked him if the song was based on my book and he said yes. So in the end, both of my books helped to shape his understanding of Hamilton’s world and way of expressing himself, and his understanding of dueling.

Q. What’s it like watching your research translated into art?

A. As a historian, I can of course point to many things in the show that aren’t necessarily historically accurate – things that are left out, shifted around, simplified or condensed – or the fact that the play focuses on a small group of elites. That said, it does some things amazingly well.

For one thing, it captures something of the spirit of America’s founding, the ongoing improvisation and fraught feelings. It also humanizes the founding. Speaking as someone who teaches that period, I can say firsthand that people don’t think of that generation as real people who were scared and confused and made big mistakes. The play has gotten people interested in the history of that period and helped them understand that it was a moment when anything could happen. Nothing was pre-ordained; there were no assumptions that the new nation would survive. People had to figure things out one step at a time.

Having people understand that America’s history specifically – and history generally – is fundamentally about people making choices and figuring things out – that contingency matters – that’s all for the better. For that reason, the play has created a supreme teaching moment.

Q. How did studying at UVA influence your work?

A. UVA is so steeped in history that it’s wonderful to study any history there. But when you study early America, you’re surrounded by what you’re studying. Peter Onuf – who I call “the mentor from heaven” – was also a big reason that UVA was such a great place to learn.

As a Hamilton scholar in particular, I found it a particularly interesting place to study. Peter regularly taught a course called “The Age of Jefferson. “ The year that I was his teaching assistant, he changed it to “The Age of Jefferson and Hamilton.” Teaching that class taught me a lot about teaching the early republic – about the importance of not breaking things down into a Jefferson-versus-Hamilton battle, but rather trying to show people the complexity of history and the human side of it. That experience was incredibly formative for me as a thinker and a teacher.

Katie McNally

University News Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today

You are using an old version of Internet Explorer. Our site is developed with the latest technology, which is not supported by older browsers

We recommend that you use Google Chrome for accessing our (or any) website. It is a FREE and modern web-browser which supports the latest web technologies offering you a cleaner and more secure browsing experience.