Digging for History

A mountaintop archaeological excavation at a World Heritage Site is bringing students face to face with the past. On a recent, …

On a recent, unseasonably cool day in Charlottesville, a group of students huddled over square, shallow dig sites on the floor of a section of sun-dappled forest at Monticello, searching for clues to previous lives.

Under the tutelage of Fraser Neiman, Monticello’s director of archaeology, 11 students are spending six weeks in the University of Virginia’s Summer Archaeological Field School at Thomas Jefferson’s home.

Neiman said two-thousand acres of Monticello provide “our archaeological sand box.”

“Our ongoing research initiative is to survey all of that property,” he said, speaking in Monticello’s archaeology lab, which is filled with artifacts recovered during years of investigation.

The work involves digging shovel test pits every 40 feet. To date, more than 20,000 dot the property, helping to reveal how land use changed during Jefferson’s day.

“The big fulcrum in our work is the 1790s, when Jefferson and planters across the Chesapeake transitioned from tobacco to wheat as the major staple crop,” Neiman said. “That has all kinds of ecological consequences, but also seems to affect the way enslaved people lived on a day-to-day basis. That is a major focus of our research here at Monticello.”

Recently, the students in the course excavated material from sites at both Monticello and James Monroe’s Highland. Take a look at how it works and what they found.

Neiman said Jefferson’s plantation was divided into what people in the 18th century called quarter farms. At Monticello, there were four, each with a cluster of slave houses.

“Monticello was called the home farm because it’s where the owner was, and the three outlying quarter farms are Tufton, Shadwell and Lego,” he said.

Monticello archaeologist Crystal Ptacek, left, directs and facilitates all of the field work.

She and rising fourth-year anthropology student Gabrielle Patterson dump soil into a large, archaeological sifting screen. A typical day features a lecture in the morning and field work in the afternoon.

Wearing heavy gloves, students push excavated dirt through sifting screens to be sure they have not missed any artifacts. This year’s class features a rarity, high school student Paige Coolidge of New York.

(Photo by Hayley Martin)

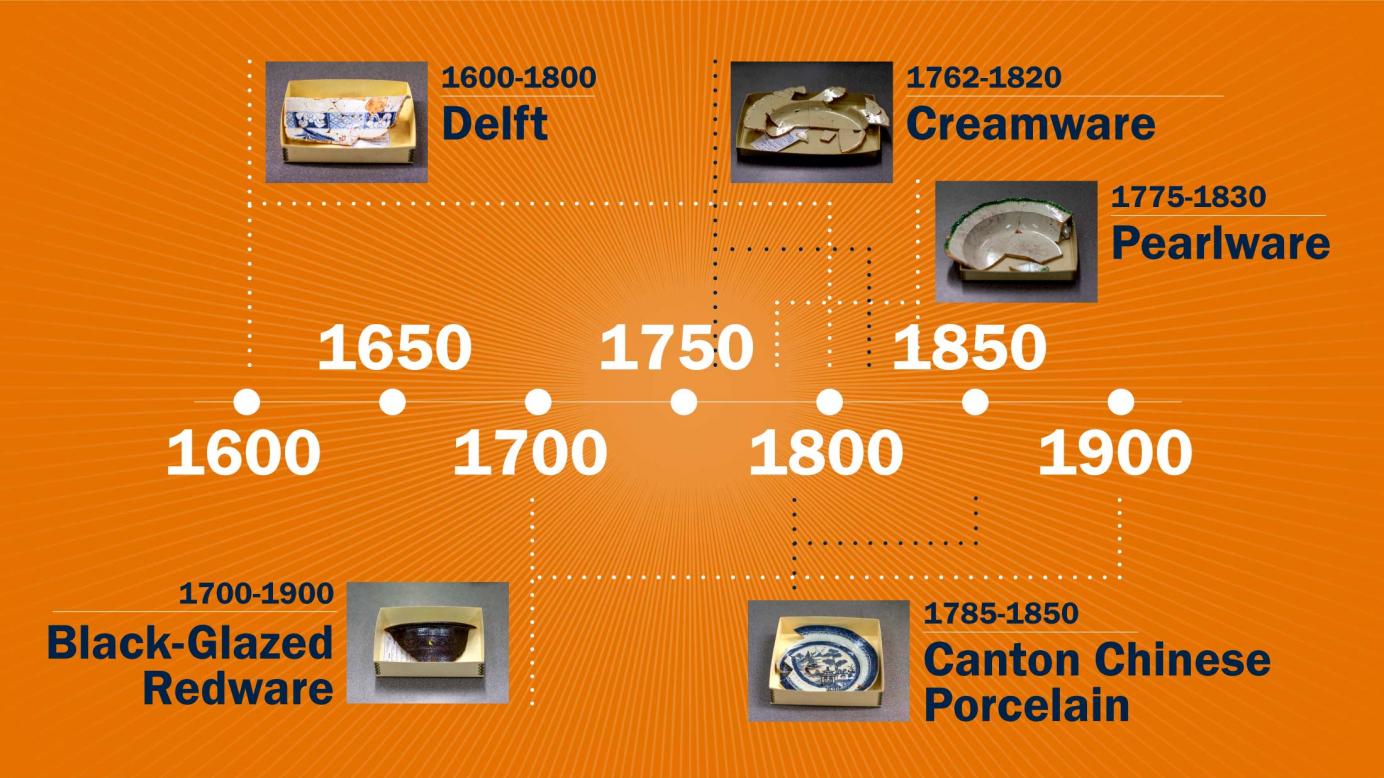

One way historical archaeologists “date” a dig site is to examine the types of ceramics they discover.

These ceramic varieties have all been found at sites at Monticello.

Students examine debris pulled from a dig site in a forest at Monticello. Anyone can apply to the field school, regardless of major, but it is a competitive process.

The field school spent another unseasonably cool springtime day working at a dig site in a broad southern pasture at James Monroe’s Highland, which made headlines recently when a newly-discovered foundation was found to be the fifth president’s home. Before that, it was long thought a more modest, existing house was his residence.

During the one day excursion, the group assisted UVA Ph.D. anthropology student Kyle Edwards, who is doing his dissertation on the changing patterns of plantation use, organization and management of the Piedmont. “Hopefully what we will be able to find is some of the remains of Monroe’s plantation and piece together how the plantation was changing through time,” he said.

The discovery of Monroe’s house shows there is still a lot to learn about Highland. “Where were the enslaved men and women living? Where are the agricultural buildings? We know Monroe had stables and a saw and a grist mill. There are even references to a smith shop or work shop,” he said. “Where are all of these things related to the Monroe house and how do they function together as part of the plantation?”

During the dig at Highland, anthropology student Gabrielle Patterson discovered this sherd. Beth Sawyer, an archaeological analyst at Monticello supporting the work, said the design and style of the porcelain suggests it is from the late 18th or early 19th century. “The decoration looks like part of a band that resembles clouds going around the rim,” she said.

“The thing that we are using to date sites is style,” said Sara Bon-Harper, the director of Highland and herself an archaeologist. “Ceramics that go on people’s dining tables were going in and out of style at a rapid rate, so they got replaced regularly and the clock that’s ticking is style.

“The next ceramic might come because of some technological changes that allow the glaze color to come out more true-white, for example, so everybody wants it,” she said.

Christopher Jackson is a rising fourth year who just transferred to UVA from Northern Virginia Community College. As part of the application process to the field school, each person is required to write a letter explaining why they want to participate in the popular program. Jackson, an archaeology major, said he wanted to learn more about Jefferson’s plantation and the slaves who lived and worked there. “Finding any evidence of that is pretty cool,” he said.

Fraser Neiman, Monticello’s director of archaeology, jumps on a shovel to begin excavating a new shovel test pit at Highland while students look on.

Jane Kelly

Media Relations Associate

Original Publication – UVA Today

You are using an old version of Internet Explorer. Our site is developed with the latest technology, which is not supported by older browsers

We recommend that you use Google Chrome for accessing our (or any) website. It is a FREE and modern web-browser which supports the latest web technologies offering you a cleaner and more secure browsing experience.