19th-century printer, journalist and essayist, Walt Whitman became America’s renowned poet many years after he shocked and unsettled American culture with the first publication of “Leaves of Grass” in 1855.

His verse broke most of the rules of convention in his day for composing poetry – such as not rhyming. Eventually, though, it captured the hearts and minds of the modern literary world.

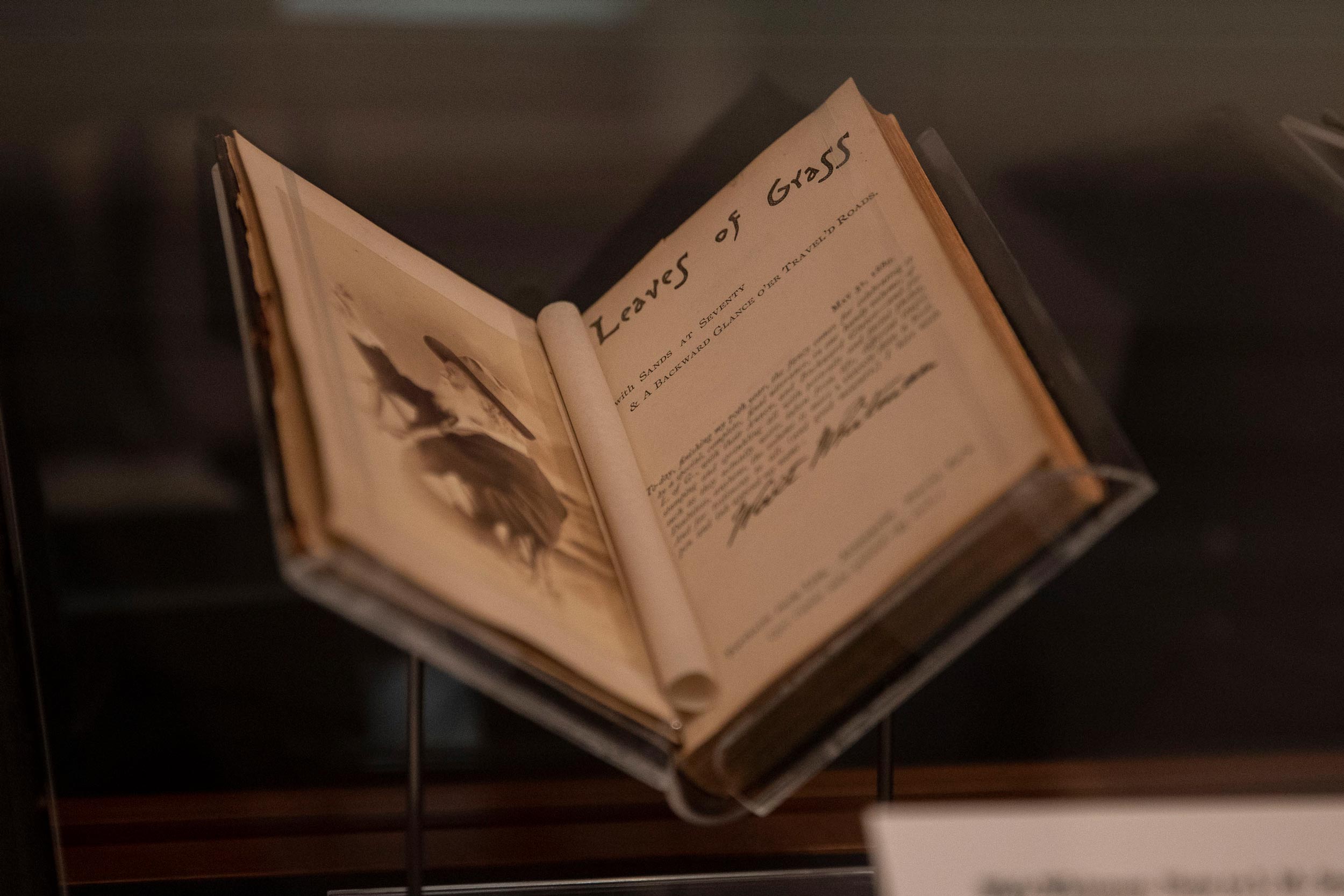

This year, the University of Virginia celebrates the bicentennial of his birth with an exhibition, “Encompassing Multitudes: The Song of Walt Whitman.” The exhibit showcases various editions of his best-known volume, “Leaves of Grass,” and handwritten versions of these and other poems, as well as other writings, including essays against slavery and about Abraham Lincoln, and letters and notes detailing his time working as a nurse during the Civil War.

With unflinching vision and an outpouring of long, flowing phrases, Whitman dove into the individual’s inner life and explored the connections between all kinds of people, and between the human and natural worlds, that seem as relevant today as they were then. He was deeply concerned about the divisiveness of the country.

From the extensive collection held in UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, to Whitman’s beloved Manhattan and the Sokan Gakkai International of Japan, Whitman lovers across the globe are highlighting the bicentennial of the American poet’s May 31 birth all this year.

The library will mark the exhibition’s opening Tuesday with chief curator George Riser giving 20-minute tours, beginning at 4 p.m. in the Main Gallery of the Harrison Institute and Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, and with a 5 p.m. panel discussion, free and open to the public. University Librarian and Dean of Libraries John Unsworth will welcome the panel to the Harrison/Small Auditorium: exhibition co-curators and poets Stephen Cushman, Robert C. Taylor Professor of English, and Lisa Russ Spaar, professor of English and director of the Creative Writing Program; and Deborah McDowell, director of the Carter G. Woodson Institute and Alice Griffin Professor of English. McDowell will read from the preface to the first edition of “Leaves of Grass,” where Whitman shows the expansive nature of his writing, giving the reader a list, “This is what you shall do” so that “your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency …”

Representing the many topics that captured Whitman’s imagination and examples of his work took a team of five curators to choose and design what books, manuscripts and other items should be included in the exhibit. In addition to the content curation from Cushman and Spaar, Riser brought in the talents of Charlotte Hennessy, now a UVA Library ambassador, and Holly Robertson, UVA Library exhibitions coordinator, on the exhibit design.

American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson was in the minority as an early supporter of Whitman’s work, but apparently wasn’t pleased that the poet put a quote from his positive review on the spine of the second edition, published in 1856: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.” The exhibit also shows one of two known copies of a letter from Emerson that Whitman had printed for promotional purposes.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that a range of poets, from Ezra Pound and Langston Hughes to Pablo Neruda and Mary Oliver, sang Whitman’s praises.

Hughes, a well-known African-American poet central to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, counted Whitman as an influence and wrote, “Whitman was America’s greatest poet and ‘Leaves of Grass’ the greatest expression of the real meaning of democracy.”

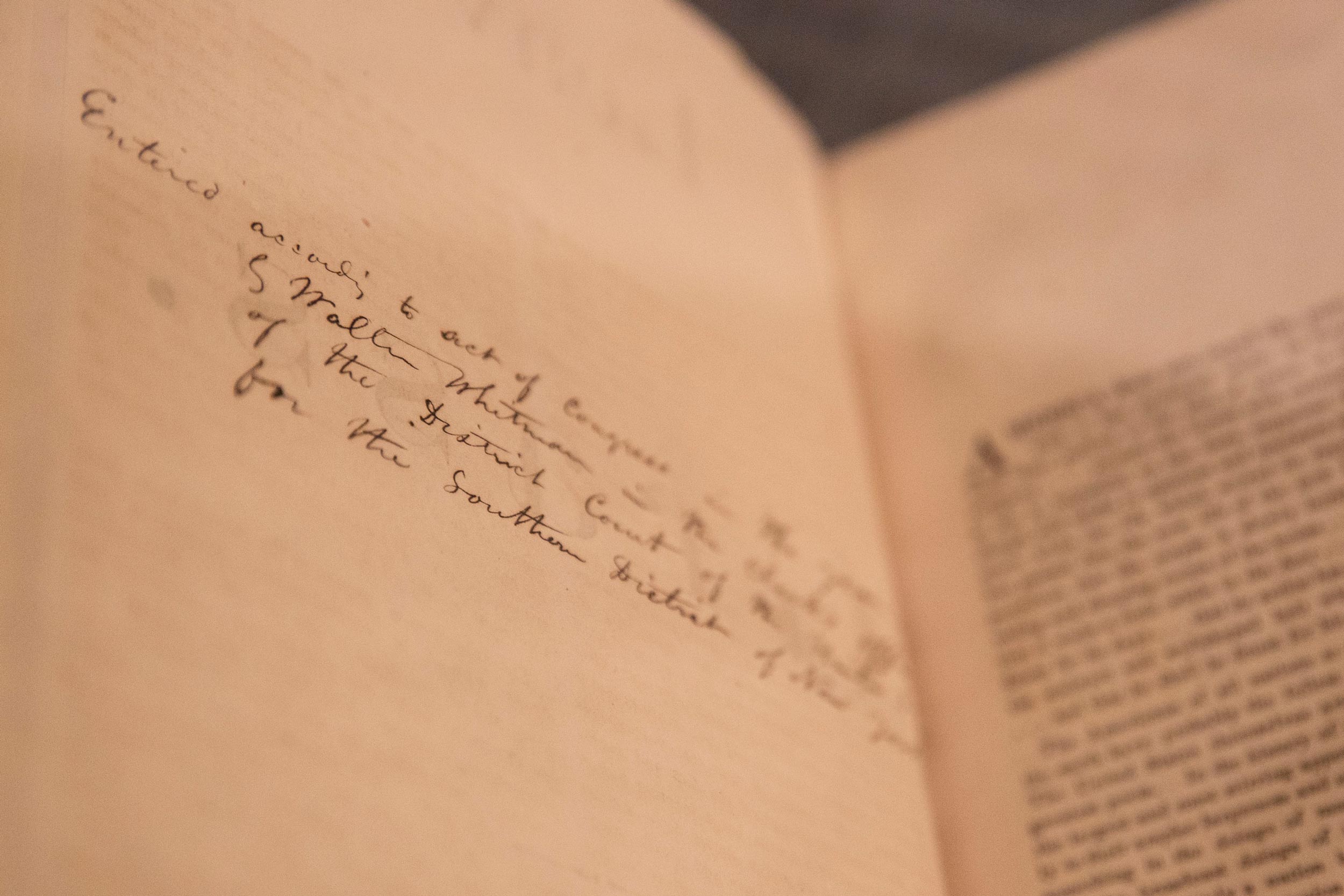

Of UVA’s 10 copies of the 1855 first edition, one from the Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature has the copyright notice written in the clerk’s hand. Riser said, “I believe there are two with the copyright notice in the clerk’s hand. I don’t know where the other one is, but all the other first editions have a printed copyright notice.”

Cushman said that Whitman knew violence over slavery had already erupted, mentioning specifically passage of the deeply divisive Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854.

“When he wrote the preface to the 1855 edition, and when he was finishing the poem that became ‘Song of Myself,’ doing what he could to hold together the disintegrating national identity, or his idea of it, was a matter of extreme urgency,” Cushman said. “In later writings, he compared the country to a single human identity, and the disintegration of one meant the disintegration of the other, at least for him.”

Whitman was a printer and journalist early in his career, and he owned and edited a newspaper, The Brooklyn Freeman, an 1848 publication aligned with the Free Soil party and movement that opposed the expansion of slavery into Western territories. Whitman considered it an emergency to address the impending disunion of the United States, according to Cushman.

“People who dismiss what they consider the glib, facile, arrogant, egotistical bear hug of Whitman’s nationalism miss this point entirely. The emergency of 1854-1855 was far more acute than our own divided situation, and Whitman was attempting to perform something like imaginative triage in the midst of the disaster. For him, this imaginative triage entailed extending himself rhetorically and imaginatively toward people not at all like him, especially women, people of color – both enslaved and free – and Southern slaveholders themselves.”

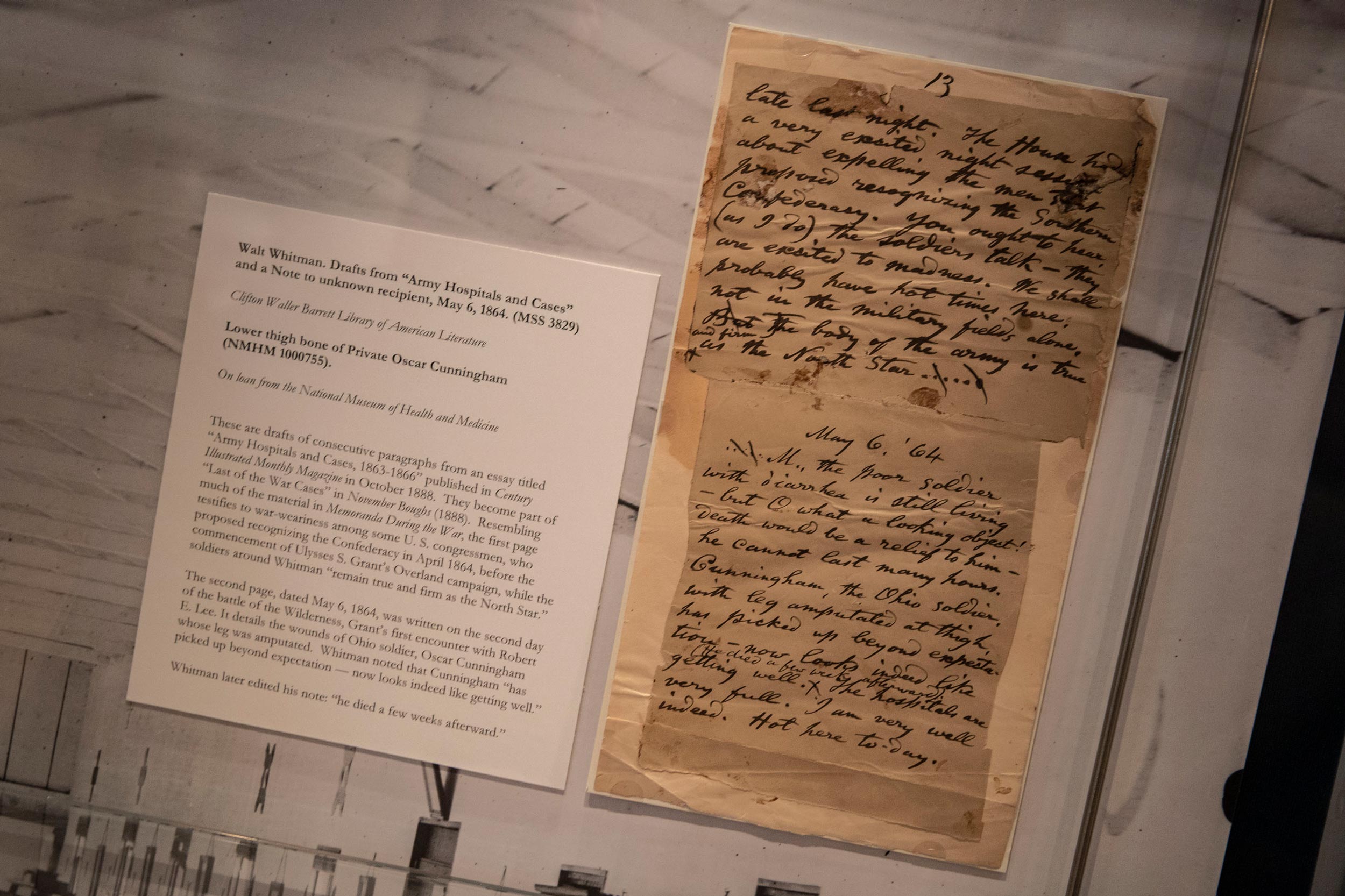

During the Civil War, Whitman spent several years as a nurse in Washington, D.C., taking notes and writing letters about what the soldiers were going through.

Years after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, Whitman gave lectures about the late president, often reciting his poem about him, “O Captain! My Captain!” On display is a card advertising a lecture in 1887, where the audience included Mark Twain, Andrew Carnegie, James Russell Lowell and Lincoln’s private secretary, John Milton Hay.

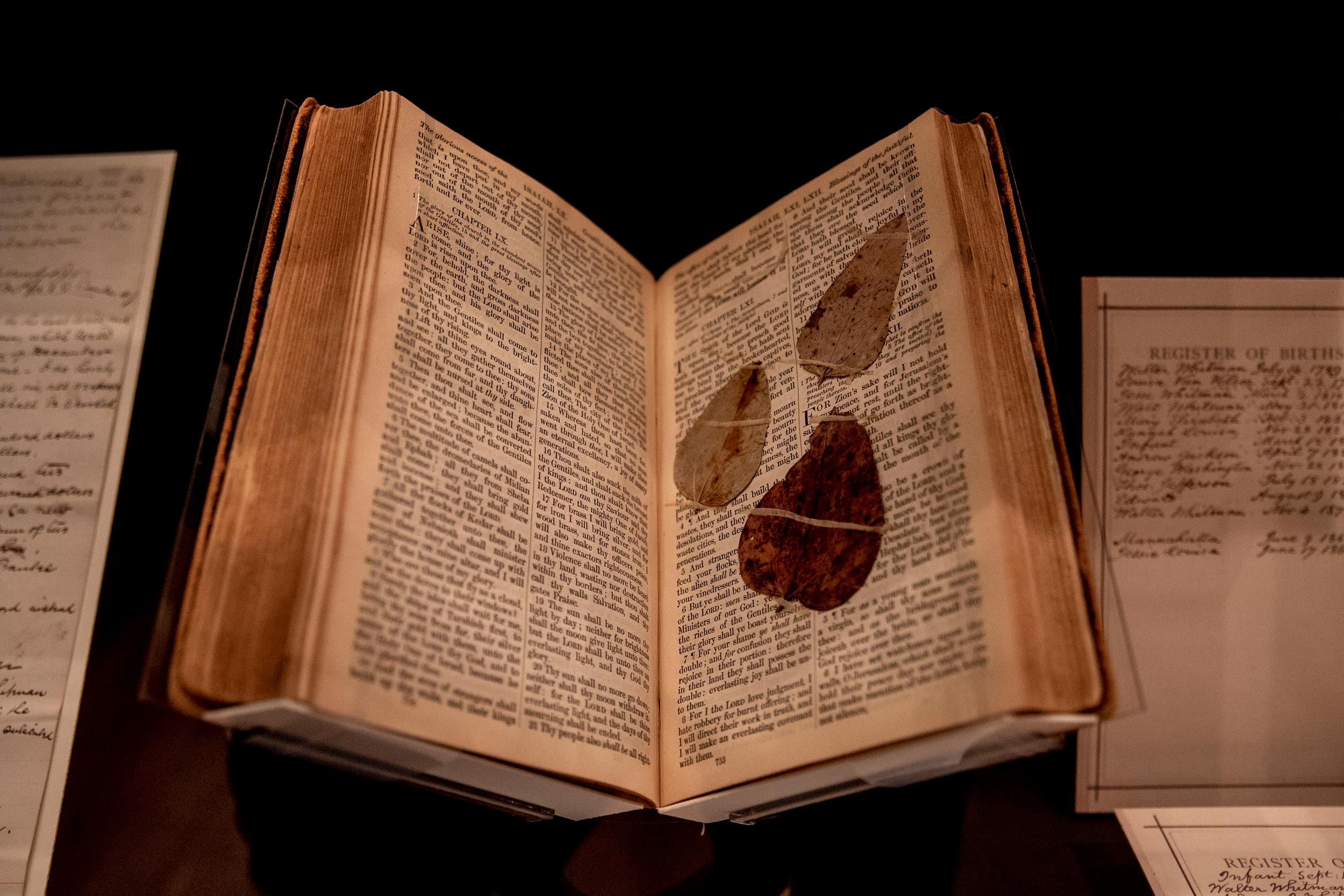

Showing his love of nature, Whitman pressed leaves in his own bible, which is part of the Barrett collection and on display in the exhibit.

Spaar described Whitman’s work as “fueled by ardor – for the natural world, for animals, the cosmos, for the polis, the individual, the country, for poetry and for ardor itself – and an attendant anxiety … [about] how to speak for the manifold selves within each vexed and prodigal self? Whitman sings selfhood again and again.”

In addition to connecting with others different from himself, Whitman also had to contend with “how to cope with his own desires – those hidden or suppressed, those expressed,” Spaar said. The exhibit says for the 1860, or third edition, of “Leaves of Grass,” Emerson urged him to take out a series of poems, “Enfants d’Adam,” because of explicit sexuality, “but Whitman declined, and these poems were singled out for praise by many women.”

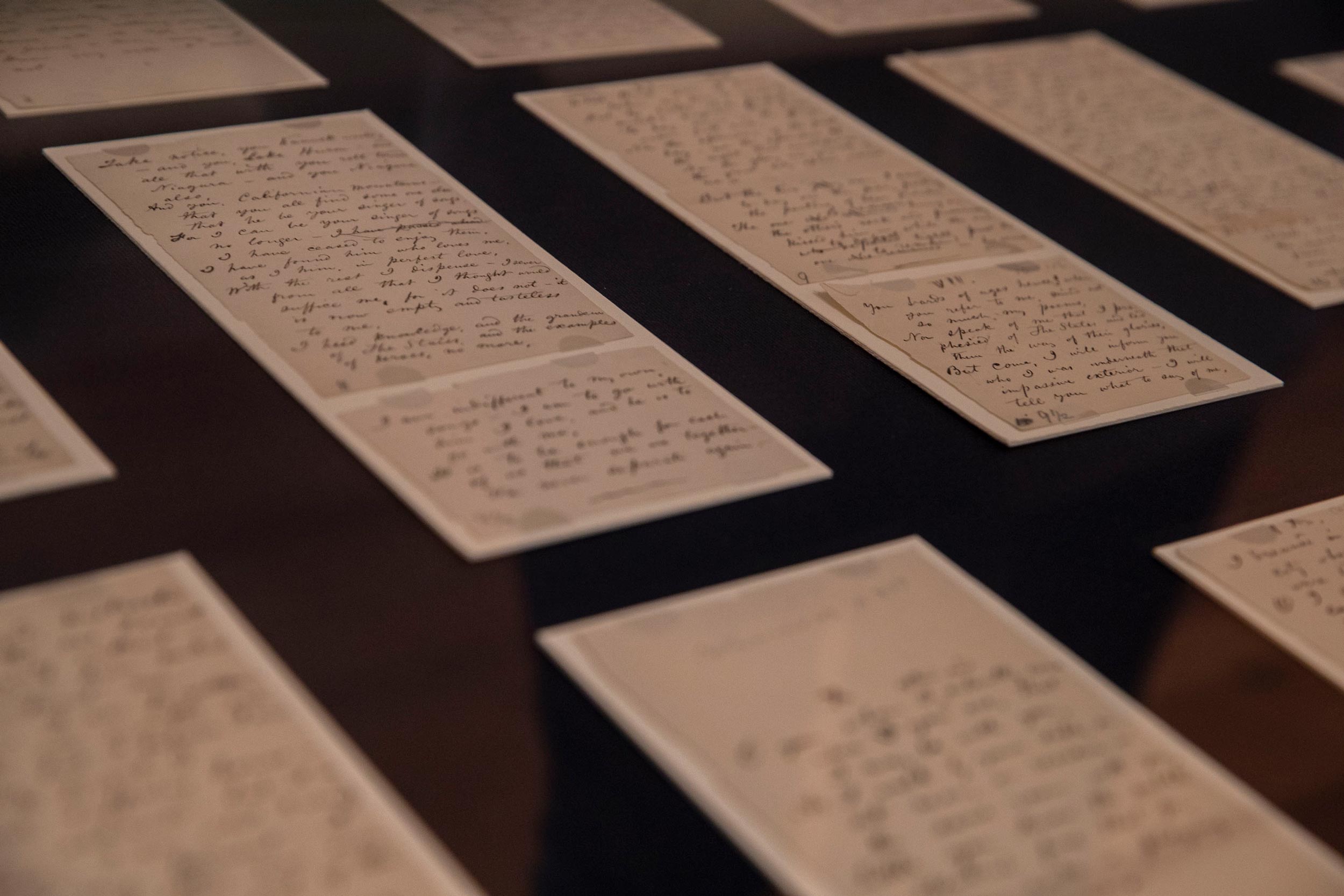

He also included another series, “Live Oak, With Moss,” interspersed with others in a section called “Calamus,” that when looked at in sequence tell of an unhappy love affair with a man. The late UVA English professor Fredson Bowers discovered this while researching Whitman’s manuscripts that were published in the third edition.

The exhibit displays the arrangement of the manuscript pages in the order they were written for the first time.

UVA’s exhibit, primarily drawn from the Barrett collection – which the scholar Ken Price, who created the Walt Whitman Archive, called “one of the great collections of Whitman manuscripts” – showcases multiple copies of not only the first edition, but also five more distinct editions and a few other printings, including the final collection Whitman put together months before he died in 1892, the so-called “death-bed edition.”

Although Price is at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, he began this digital archive with UVA’s Institute of Advanced Technology in the Humanities, when University Librarian and Dean of Libraries John Unsworth was the institute’s director.

Whitman revised the collection of “Leaves of Grass” continuously over his life, introducing new work and taking out some poems. This version from 1889 shows a photograph of him from later in life with a butterfly perched on his finger. It turns out the insect was made of cardboard.

Anne E. Bromley

University News Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today