Mary Shelley published “Frankenstein” in 1818, but Shelley revised her classic novel more than once and added a third edition in 1831 in response to critical reaction.

Two hundred years later, the novel remains among the most-taught in high school and college classes. But which version? Students who turn to the internet today for the text as part of a class assignment will encounter a monstrous search result with multiple versions of the text, plays, comic books and more.

That’s a problem.

Amid the uncertain origins of some internet news sites, social groups and an avalanche of information available with a few clicks, college students are getting lost – this time in virtual collections of books.

Students are grabbing digitized copies online when they’re assigned certain books without knowing whether they’ve found a reliable version, not to mention the right edition.

Even well-known, copyright-free classics of literature that are digitized could be suspect.

Scholars and other academic staff, including librarians with technological expertise, have been working on raising standards for some years, but it’s still an ongoing battle, according to University of Virginia English professor John O’Brien and Christine Ruotolo, the University Library’s director of arts and humanities.

With a recent National Endowment for the Humanities grant, they are working with colleague Tonya Howe, an associate professor at Marymount University, to build a website that teachers and students can count on for providing accurate, authoritative editions of American and British literature spanning the formative period of the modern transatlantic world, from roughly the mid-17th century to the 19th century.

The open anthology they’ll collaborate on will expand their previous work into a larger platform of literature that students and teachers can use with confidence.

What’s Wrong with ‘Frankenstein’ and ‘Gulliver’s Travels’?

Take a book like “Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus,” which continues to be a wildly popular story 200 years later. Shelley first published it in 1818, but she revised it and added to the third edition in 1831 in response to critical reactions.

Besides various editions, “Frankenstein” sparked an ongoing series of plays and movies, comic books and comedies. Although Shelley never actually wrote, “It’s alive! It’s alive!” the story of the young scientist defying nature and making his own creature of human parts has long lived through hundreds of recreations.

“Frankenstein” is the most-taught book in high school and college, O’Brien said, yet students usually don’t know whether they have downloaded an authoritative edition. The ebook, for example – enticing because it can be downloaded for free – does not include which edition it came from.

That means in the classroom, students literally are not on the same page, Ruotolo said.

Undergraduates are turning to the internet to download books for free to help offset the high cost of textbooks they have to buy, especially those hefty tomes in the sciences and economics, O’Brien and Ruotolo agreed.

Andrew Michael, who graduated last year with a major in English and is in the master’s program now, is taking his third class with O’Brien, and began working with the Scholars’ Lab on an earlier project for one of O’Brien’s classes.

“Having spent the last five years as an English major, one of the biggest problems I’ve seen is the lack of options for quality online versions of the texts we use in class,” Michael said. “Whether we just want to search for an important passage or just don’t want to pay $30 for a book we’re only going to read once, many students feel that having a quality digital version of what they’re working on is critical to their understanding of the material.”

These older novels, often required reading in survey courses on literature, are in the public domain – and that’s why publishers and companies are racing to put them online without having to worry about copyright law. And while free access is a key component, students are not equipped to evaluate what they are getting.

“Gulliver’s Travels,” for example, similarly exists in several versions with two major editions published in 1726 and in 1735.

“Either one is interesting,” O’Brien said, “but you need to know which one you want to read and a Google search doesn’t necessarily tell you.”

O’Brien shows students several editions of Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels.” Chris Ruotolo, third from right, and O’Brien received an NEH grant to digitize authoritative editions of online books.

O’Brien shows students several editions of Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels.” Chris Ruotolo, third from right, and O’Brien received an NEH grant to digitize authoritative editions of online books.

“While the widespread free availability of numerous literary and historical texts online makes possible new modes of inquiry barely imagined a generation ago,” Howe wrote from Marymount, “the accuracy, quality and authority of digitized texts are far from uniform.”

For the University Library, issues of authoritative editions are as crucial as open access and free availability.

“The library has an interest in providing access to high-quality digital texts for use by UVA students, as well as the general public,” Ruotolo said. “Part of our role in this project is to ensure that reliable digital editions are preserved and discoverable for use by future generations of scholars.”

Making Research Come Alive

Both Howe and O’Brien have already created experimental versions of online anthologies that they are using in their classes. Along the way, students have assisted their professors, providing annotations and combining multimedia components – with images or video, for instance – to enrich the context.

The NEH grant, which provides almost $73,000 in funding for 18 months, will support the development of “Literature in Context,” an open-access, curated and classroom-sourced digital anthology of British and American literature in English. It will merge the two existing experimental classroom projects that Howe and O’Brien developed separately – Howe’s “Novels in Context”and O’Brien’s “Open Anthology of Literature in English.”

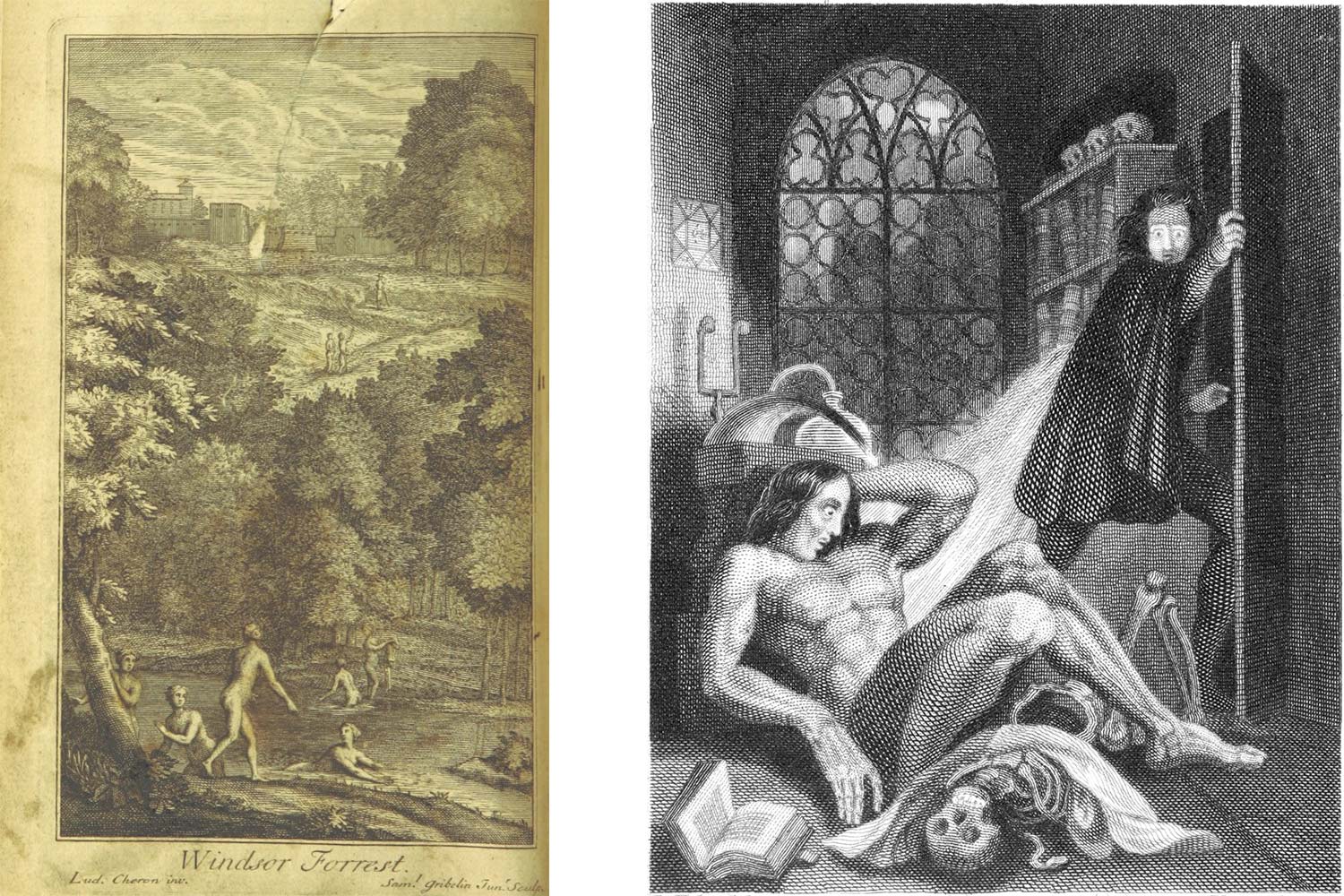

An engraving of Windsor Forest, the frontispiece to the 1720 edition of the poem by Alexander Pope, and the first depiction of “the Creature” by Theodore von Holst, from the 1831 edition of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.”

An engraving of Windsor Forest, the frontispiece to the 1720 edition of the poem by Alexander Pope, and the first depiction of “the Creature” by Theodore von Holst, from the 1831 edition of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.”

Although many scholars, librarians and others have written about the need to make sure digital texts are reliable and accurate, no one has solved the problems involved with formatting and navigating long books, among other challenges, O’Brien said.

A premise of both projects is to spur learning through student-faculty collaboration.

“The future of publishing, the work of learning, and the demands of public discourse are changing,” Howe said. “As teachers and scholars, part of our charge is to ensure that these changes benefit our students’ intellectual, ethical and civic growth.”

O’Brien has used his online anthology as the sole reading source in his survey courses on 18th-century British and American literature, with students working on annotating the texts as part of the process of learning research and analysis.

As an undergraduate, Michael worked as an encoder and editor on O’Brien’s “Open Anthology of Literature,” and is working for him on two other digital projects now. He annotated some of Alexander Pope’s “Windsor-Forest” and Horace Walpole’s “The Castle of Otranto,” the latter often referred to as the first Gothic novel of suspense and the supernatural. Currently taking O’Brien’s “The Transatlantic 18th Century” course, he and other students are “helping to digitize and annotate the complete autobiography of Benjamin Franklin so that we can hopefully publish (online) a high-quality, and most importantly free, version of this important part of history,” Michael said.

“All of these projects have given me a much deeper understanding of the various pieces of literature I’ve worked on,” he added.

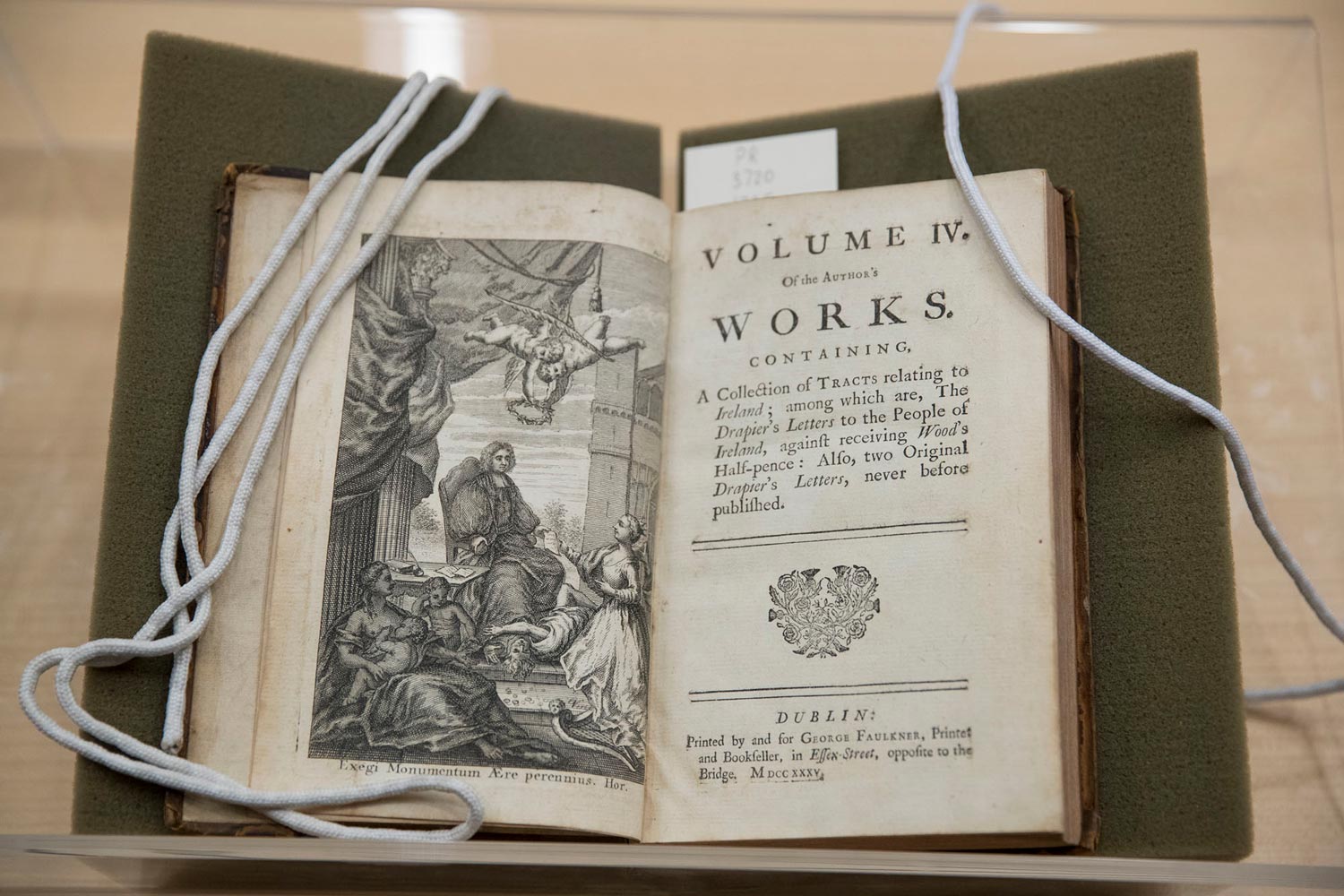

This semester, one student group in O’Brien’s undergraduate course on “Satire” is working on annotating Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels.” UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library contains a great collection of the most important editions of Swift’s work, O’Brien said.

For classics like “Gulliver’s Travels,” many editions have been published, but it’s not clear where online copies came from. This is the first Dublin edition, published in 1735.

For classics like “Gulliver’s Travels,” many editions have been published, but it’s not clear where online copies came from. This is the first Dublin edition, published in 1735.

In his classes’ work on the anthology, students have captured and made a resource that will be used and expanded.

“This is primary research,” O’Brien said.

Ruotolo added, “Students are building a repository of scholarship and public knowledge.”

“When students finish a class, it’s as if their work dies with it at the end of the semester,” O’Brien said. “In this ongoing project, they’ll be making contributions that live on.

“We hope to build on this beginning, filling in a very full archive of texts from this period, and then extending the scope to create a full anthology of open-access literary texts that have been curated, edited, annotated, and supplemented with digitized resources – images, audio files, maps, timelines, etc. – that take advantage of the digital environment in a way that no print anthology can,” he said.

Anne E. Bromley

University News Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today