Whatever you do, don’t call them “cute.”

That’s what collector Caroline Brandt advises when it comes to miniature books, whether the small volume measures the size of the tip of a finger or a few inches in circumference and looks like Cinderella’s carriage to the ball.

Brandt, who is 90 and lives in Richmond, has been collecting miniature books for almost as long as she can remember. In 2005, she donated her collection to the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library – some 15,000 volumes, which occupy just two sides of compact shelves in the rare book archives.

Now is the time – through August – to see an exhibition of the tiniest books from one of the largest collections in the United States.

A huge amount of care and thought went into selecting the miniature masterpieces to display in the First Floor Gallery of the Harrison/Small Building. Library curator Molly Schwartzburg worked on the exhibit, “Eminent Miniatures,” working from a list Brandt had been making over the years of publishers and printers that are well-known for their more standard-sized books, but who had also produced miniature books for various reasons.

Brandt is still collecting and still participating in the Miniature Book Society, an international group that she co-founded with other mini-book lovers in 1983. In the U.S., a book is considered miniature if it’s no bigger than three inches in width, height and thickness, according to the society’s website.

“I’ve always liked anything miniature,” Brandt said during a recent phone call. “What the artists do to create these books is incredible … with the typefaces and the bindings. It takes twice as much work to make a miniature book as it does to produce a big book,” said Brandt, who named the McGehee Miniature Book Collection after her first husband, C. Coleman McGehee, a UVA alumnus.

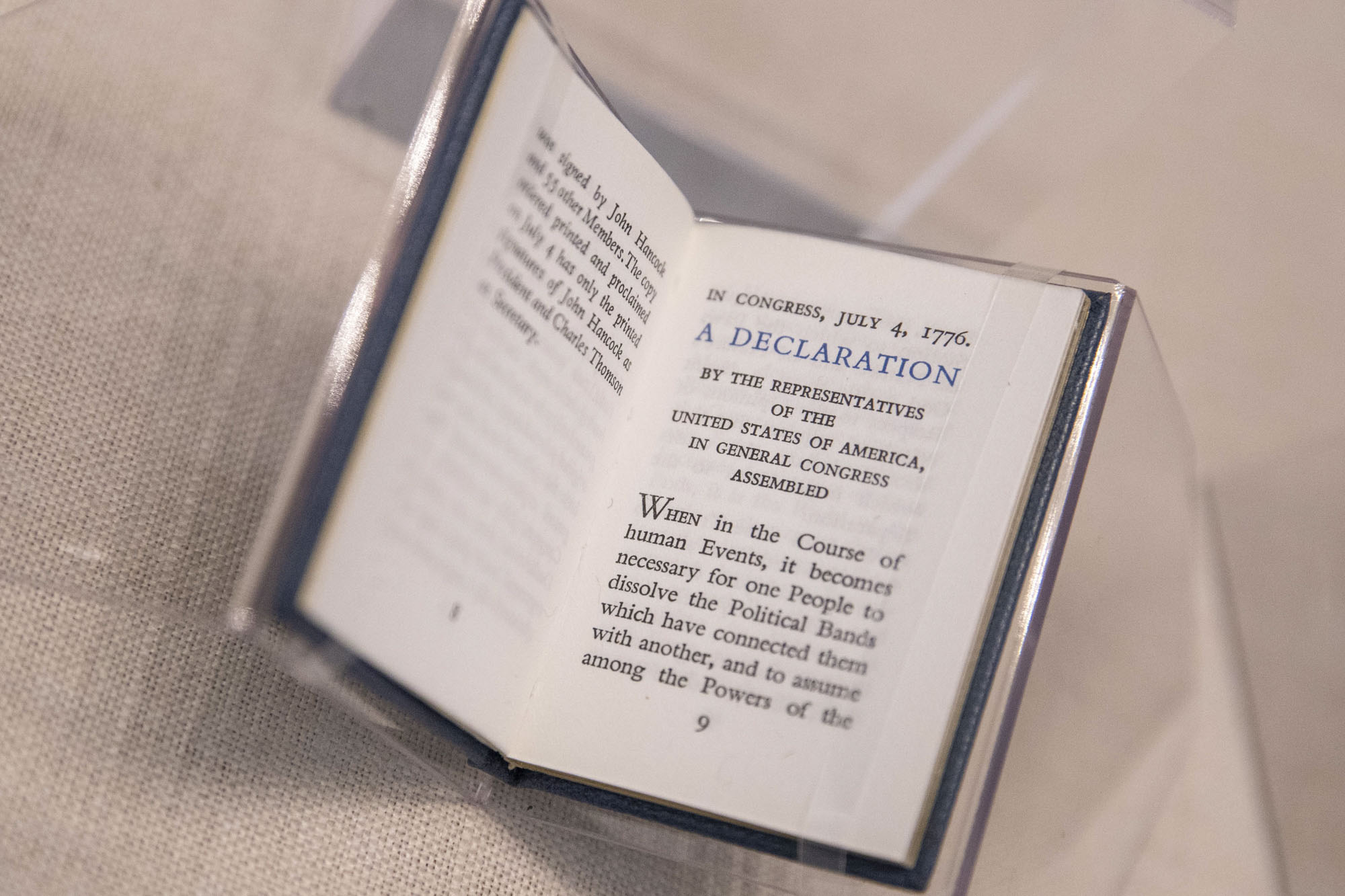

There’s almost no country in the world that hasn’t made some kind of little book, Brandt said, and no subject that hasn’t been covered, from the Bible to the Declaration of Independence to an early 19th-century contraception guide. (She’s still looking for that edition, she said.)

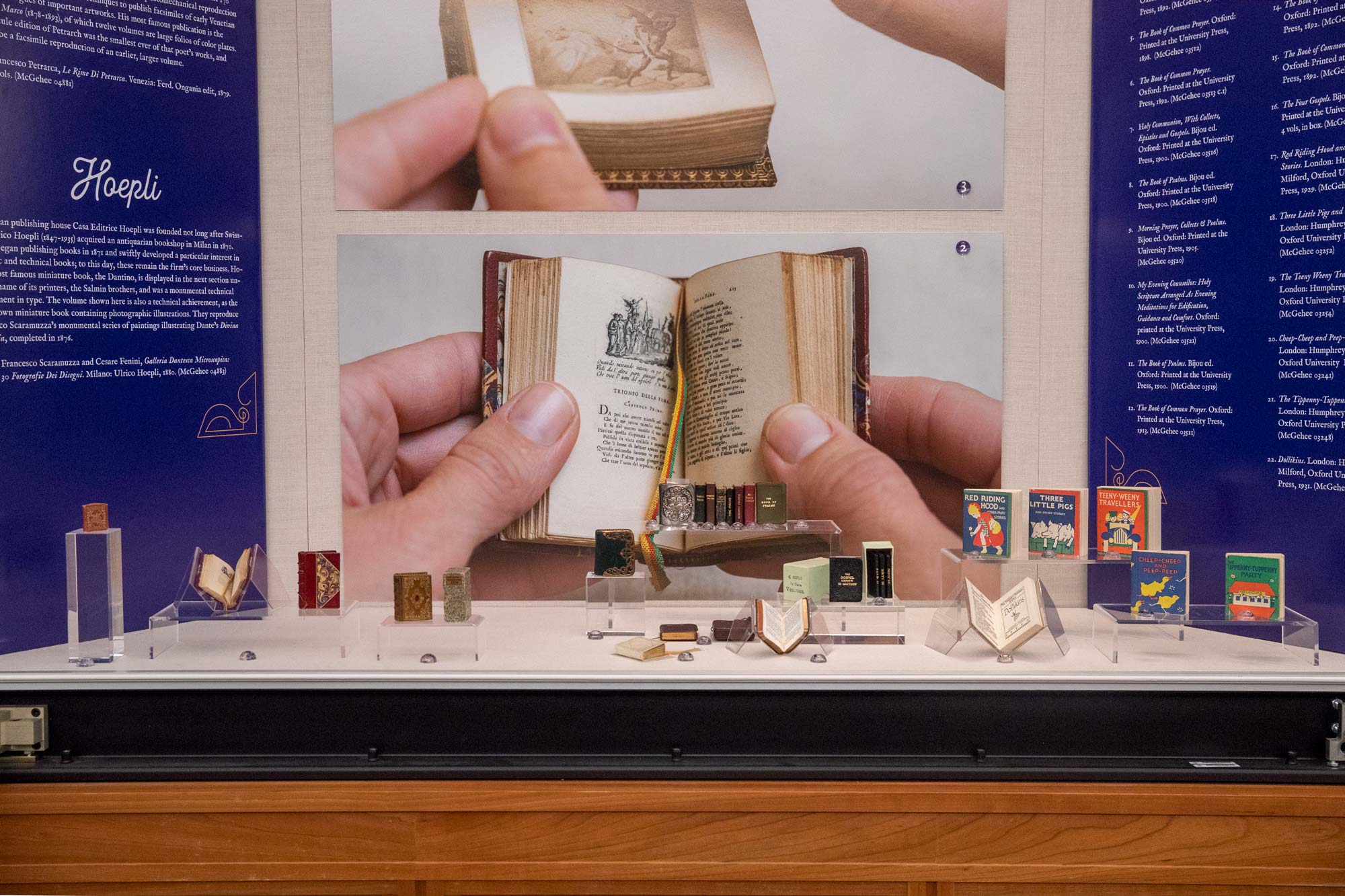

The exhibition was set up to coincide with the Miniature Book Society’s annual meeting, the “Grand Conclave” as it’s called, held recently at the Omni Hotel on the Downtown Mall. Shane Lin, a doctoral student in the UVA Corcoran Department of History and a senior developer in the Scholars’ Lab, provided photographs of hands holding miniature books. The photos were produced in oversized format to form the backdrop of the exhibition cases.

Also coinciding with the exhibit, the Small Special Collections Library and the Virginia Center for the Book will hold a family event, “Day of Mini,” on Aug. 25 from 10 a.m. to noon. Visitors can decorate their own mini-books and see a demonstration of a miniature printing press.

These books are appealing to children because of their scale, Curator Molly Schwartzburg said, but anyone can appreciate the history and artistry of the collection.

In the meantime, UVA Today provides this photo essay to give you a glimpse of some of the tiny treasures.

(Photos by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications, unless otherwise credited)

A large photo of a 19th-century Italian publisher’s wee edition of Petrarch’s poems looms over the other mini-books on display here. Starting in the late 19th century, the Oxford University Press published a series of children’s books (on right) and religious gift books such as the “Book of Common Prayer” to finance its massive Oxford English Dictionary project, and the venture was a huge success.

The smallest complete work printed with movable type, a letter written by Galileo, was published in 1896 by a prominent printing firm, the Fratelli Salmin. When the type designer, Antonio Farina, first designed the typeface occhio di mosca – fly’s eye – more than 60 years earlier, it was too small to print.

Curator Molly Schwartzburg wrote about the exhibit in the Small Special Collections Library blog, “Notes from Under Grounds”:

“In this exhibition, you will see that when great printers, binders, and publishers decide to make miniature books, the results are stunning. These are works of exquisite craft, structural diversity, and outsized beauty.”

Publisher Achille St. Onge of Worchester, Massachusetts, oversaw the production of mini books from 1935 to 1977 and published traditional, often revered texts, including this edition of the Declaration of Independence. His works are known for their uniformity of size, elegance and clarity of design.

Some miniature books were produced to be easily portable. Some were produced for marketing, as advertisements. Most, if not all, attain the level of works of art. Making miniature books has always been a feat of technological or artistic experimentation, according to Schwartzburg.

(Photo by Shane Lin, courtesy of Small Special Collections Library)

Not only was Dante’s “La Divina Commedia” published in miniature format, but also an 1876 edition, “Galleria Dantesca Microscopia,” that reproduces photographs of artist Francesco Scaramuzza’s paintings of scenes, like this winged demon, from a standard-size edition of Dante’s masterpiece. The Italian publisher Casa Editrice Hoepli published both miniature books.

(Photos by Shane Lin, courtesy of Small Special Collections Library)

Miniature books were also published in 19th-century America. Jane Hamilton, a bookseller in Philadelphia, ran a small publishing business and produced at least four little books, including “Gentle Thoughts,” with its whimsical drawings, in 1864.

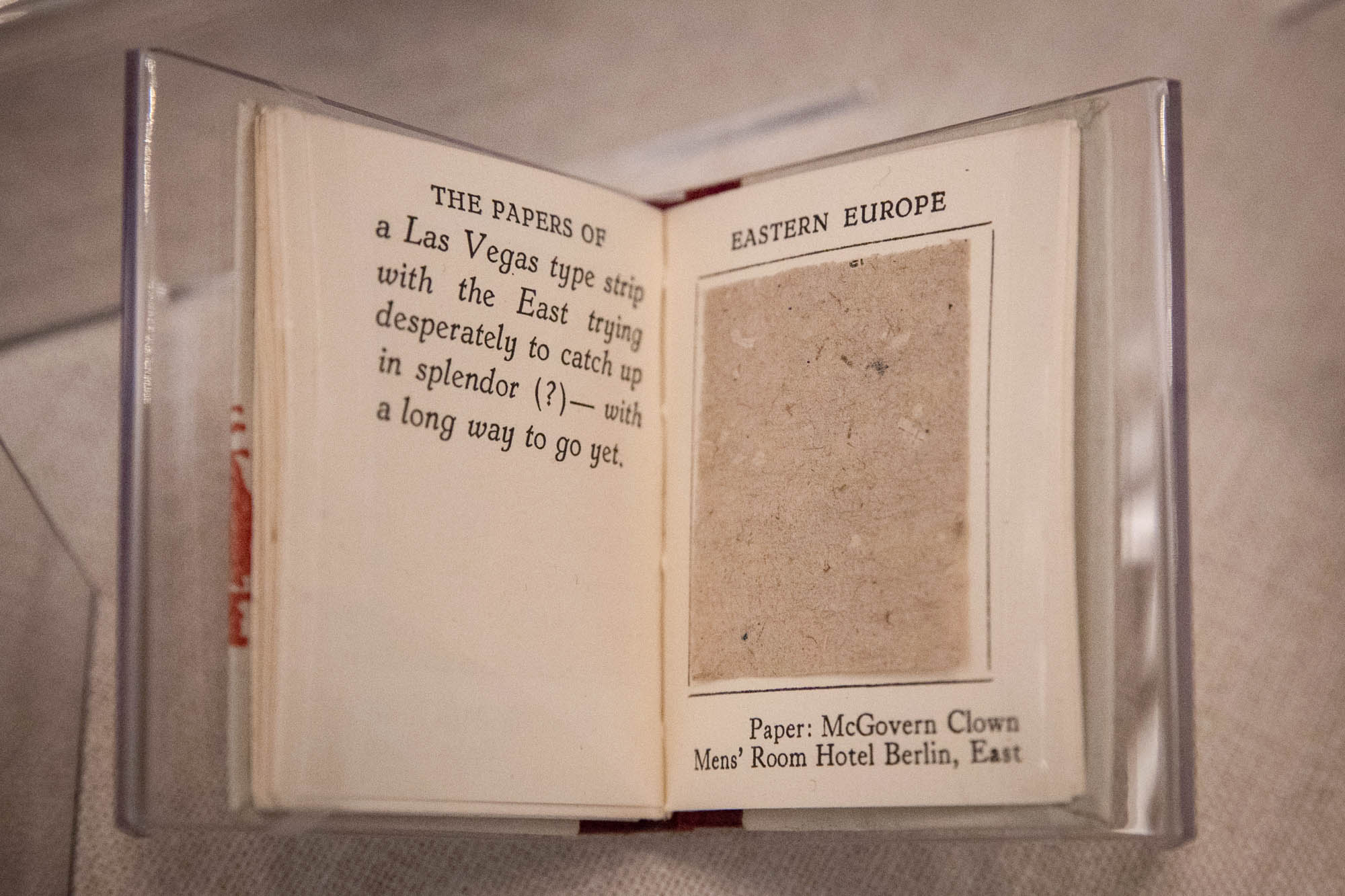

Some publishers seemed to have a lot of fun with their tiny treatises and resourceful volumes – “high brow and low brow,” Schwartzburg said. In the 20th century, Glen and Muir Dawson kept their father’s family business, Dawson’s Book Shop, going and published “a dazzling variety of miniature books,” she said. One of her favorites is this 1966 mini-book, “Paper Samples,” which contains actual toilet paper samples from European hotels.

Even UVA’s tradition of celebrating Edgar Allan Poe’s short time on Grounds is represented in the exhibit. Two unusual small objects of his short stories shown here go beyond a simple book with front and back covers. “The Black Cat” has a cat’s face for a cover springing out of a tiny box. “The Premature Burial” comes with the story fitting into a tiny coffin, complete with a scared face and hands.

Even UVA’s tradition of celebrating Edgar Allan Poe’s short time on Grounds is represented in the exhibit. Two unusual small objects of his short stories shown here go beyond a simple book with front and back covers. “The Black Cat” has a cat’s face for a cover springing out of a tiny box. “The Premature Burial” comes with the story fitting into a tiny coffin, complete with a scared face and hands.

Master bookbinder Jan Sobota worked in his home country of Czechoslovakia until defecting to the U.S. with his wife, Jarmila, in 1982. She trained under him and the two ran a gallery, taught bookbinding and began producing mini-books. They continued their business when they returned to the new Czech Republic in 1997. The exhibit shows the range of their artistry.

(Photo of Jan and Jarmila Sobota books by Molly Schwartzburg. Photo of closed Sherlock Holmes book by Shane Lin, courtesy of Small Special Collections Library)“Jan Sobota gained renown for his innovative bindings, works of art that succeed in being both functional and sculptural,” Schwartzburg wrote for the exhibit. “Individually and in collaboration, he and Jarmila produced a significant body of miniature books, whimsical and often witty works that take full advantage of the expressive opportunities of diminutive scale.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Hound of the Baskervilles: Conclusion & Retrospection” in 2006 provides a good example, as do the Poe pieces and the tiny pumpkin carriage that contains the Cinderella fairy tale.

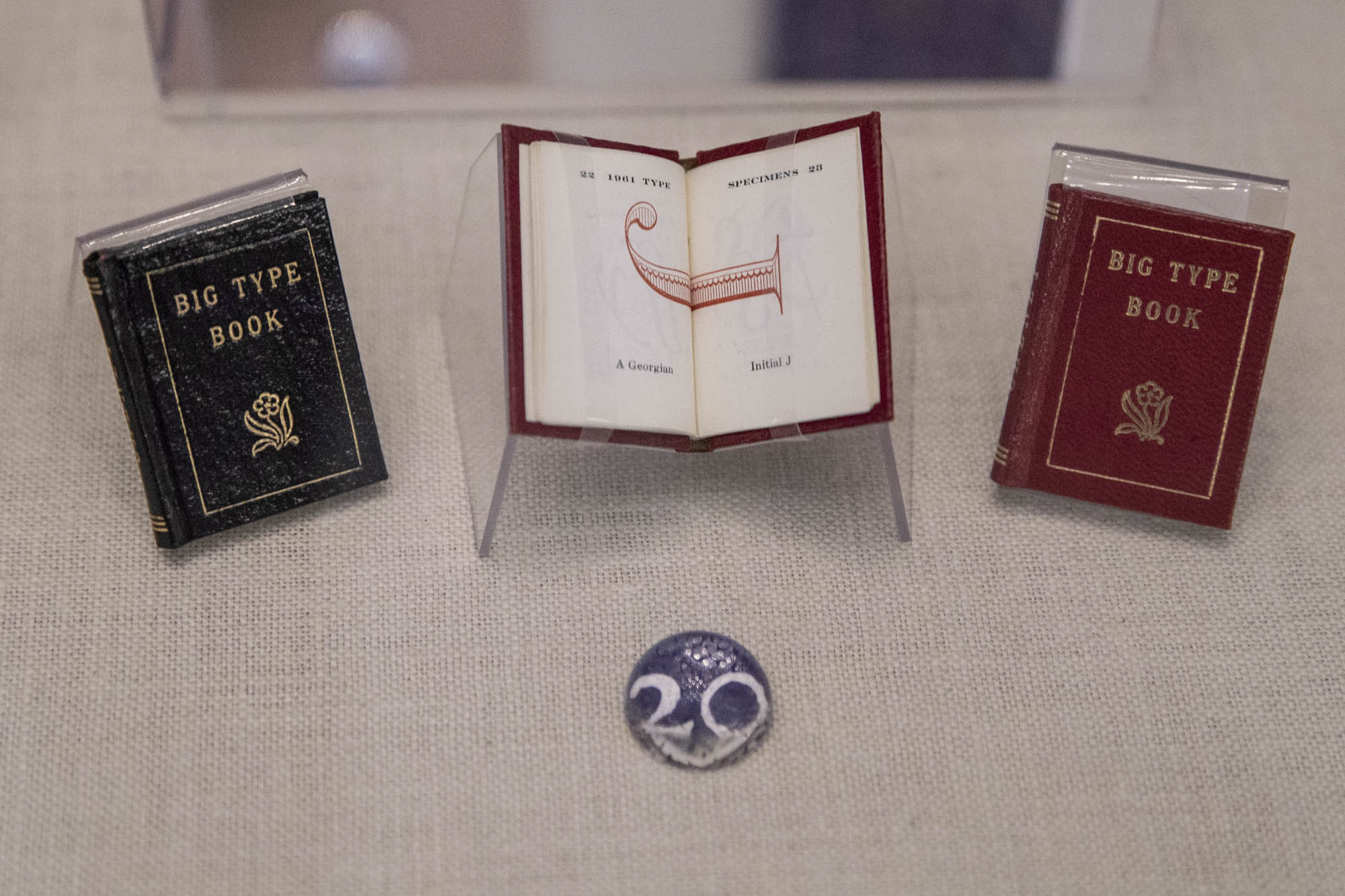

Book makers choose the subject matter of their miniature books to suit the scale, Schwartzburg pointed out. They can be beautiful or playful, and often both. There are tiny books that present an ABC of a typeface, such as these examples, where the large size of the type in the small format is appropriate, she said.

The 15,000 volumes of the McGehee Miniature Book Collection are stored in microfilm boxes and occupy just two sides of compact shelves in the rare book archives.

A few miniature Bibles are usually on view through the windows of the special collections vault, but this is the biggest exhibit of mini-books so far, Schwartzburg said – but it represents only 0.006 percent of the McGehee Collection.

Anne E. Bromley

University News Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today