Two UVA students, both pursuing Master of Architecture degrees, were honored in a design competition that pitted their work against that of top professionals in the region.

One entry looks halfway around the globe to bring fresh life to the Yamuna River in India’s capital, New Delhi, while the other imagines a new kind of museum in the heart of America’s capital city.

Facing competition with architecture firms around the region, University of Virginia School of Architecture graduate students Joe Brookover and Mohamed Ismail each garnered honors in the 2016 Unbuilt Awards, run by the Washington, D.C. chapter of the American Institute of Architects. The awards recognize design ideas that push conceptual exploration and innovation and generate new discussion in design thinking.

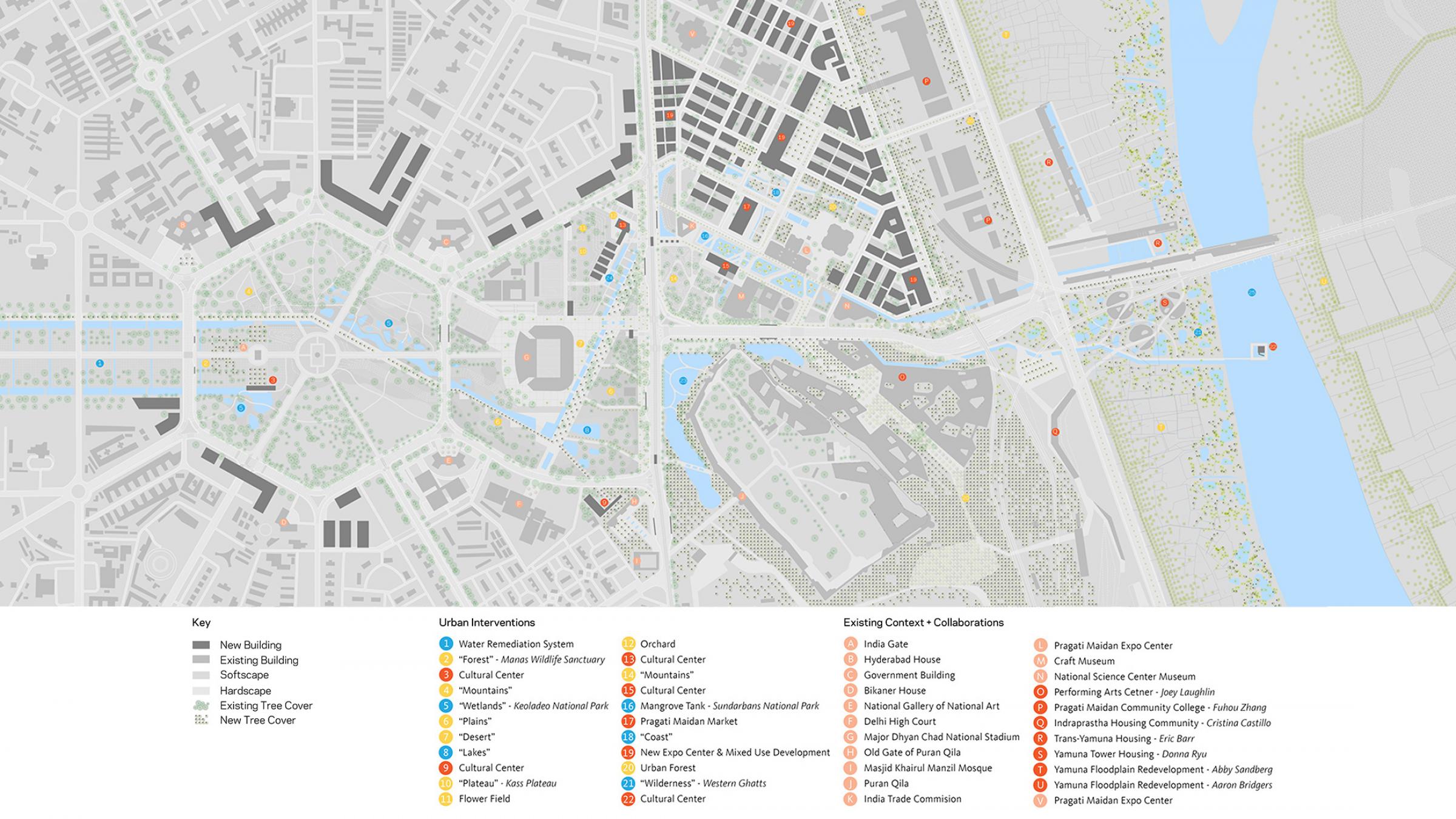

Brookover was one of two entrants to receive an Honor Award and the only student to earn that distinction. His submission offers a glimpse of the School of Architecture’s long-term research initiative, “Re-Centering Delhi,” a three-year collaboration developing urban planning solutions for the Indian capital.

Ismail’s design, called “Collecting the World (as we know it),” was one of two student entries to win a Merit Award, awarded to seven entries in total. His theoretical design for a new Smithsonian Institution museum on the National Mall sprang from one of his classes at UVA, which asked students to imagine how the institution might develop a museum on a vacant site.

UVA Today caught up with Brookover and Ismail, both master’s students, to learn more about their designs, shown in the renderings below.

Britain’s decision to relocate India’s capital from Calcutta to New Delhi catalyzed sprawling development in the urban metropolis and moved the growing city away from the Yamuna River, which had once defined its history and culture. Brookover is one of several UVA students working in design studios for the Re-Centering Delhi project, which aims to restore the river and bolster connections between it and New Delhi residents. Pankaj Vir Gupta, the Harry S. Shure Visiting Professor of Architecture, and Iñaki Alday, professor and chair of UVA’s Department of Architecture, lead the project.

“The studio project really embodied why I decided to come to UVA,” Brookover said. “Delhi is a growing metropolitan area with a lot of contentious social and historical problems, and this was a great opportunity to see how architecture and design could allow a shared social identity to emerge over time through moments of personal recognition and shared experience.”

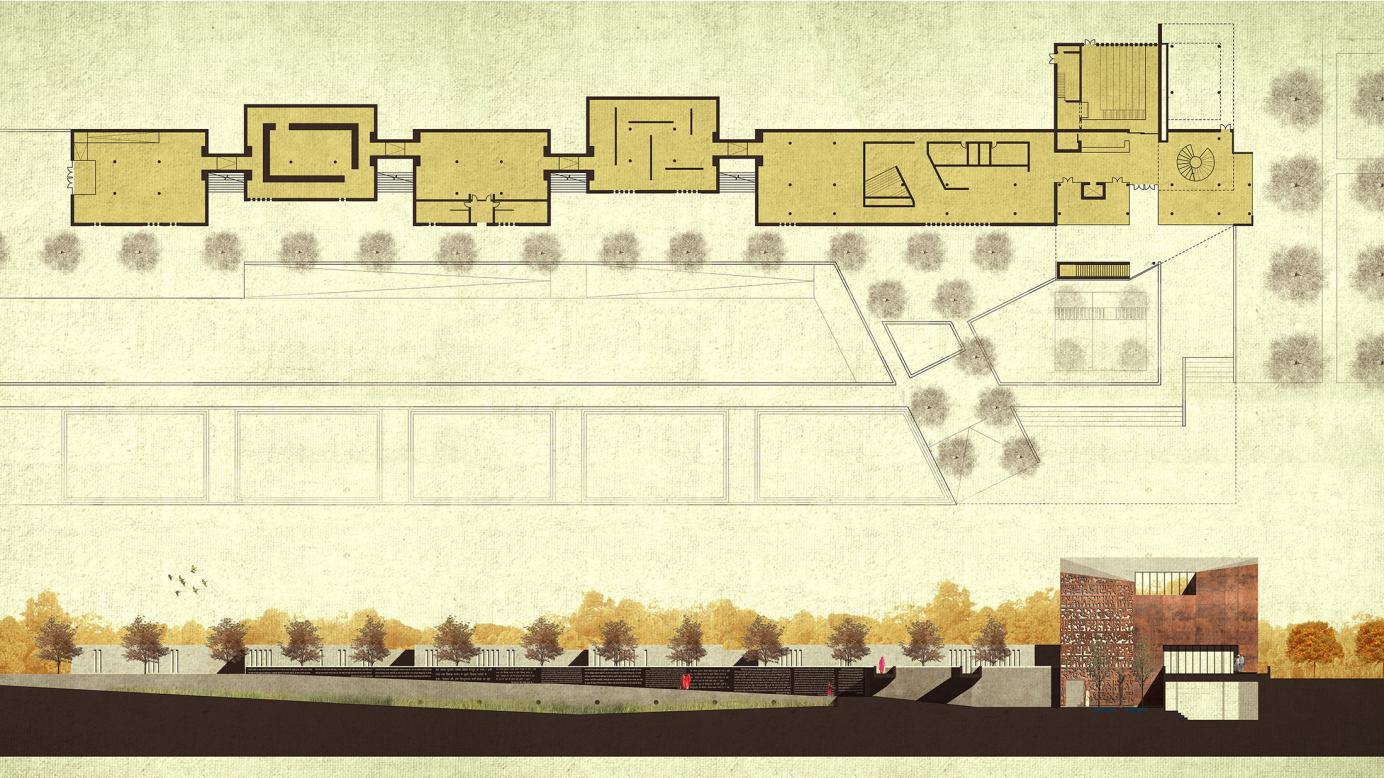

Brookover traveled to New Delhi, the capital city at the heart of India’s Delhi region, with his classmates last fall and returned envisioning a series of parks and cultural institutes along the river that could serve as educational and community centers for health, education or the arts.

“Delhi was the most interesting place I have ever been,” Brookover said. “It is kind of on an edge, ready to really take off or to succumb to itself.”

He hopes natural spaces, like the one in his design above, could provide opportunities for residents to enjoy the refreshment of shade and water, gaining respite from a city where temperatures can soar well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Brookover’s cultural institutions were inspired by similar concepts that sprung up in the 1950s and ’60s, celebrating Indian arts and culture after the country gained independence in 1947.

His design calls for art and architecture reflecting the diverse cultures of India’s various regions, coming together in the capital.

In reimaging this portion of New Delhi, Brookover also drew inspiration from Rana Dasgupta’s book, “Capital,” which chronicles the transformation of New Delhi through interviews with citizens from all walks of life.

“It is easy, when you see a city of millions, to see it as a mass, but I was really drawn to the individuals of the place,” Brookover said. “They are the ones who experience the problems, create the solutions and have to live it everyday.”

In another design studio project last fall, professor Shiqiao Li asked students to design a museum tracing the interaction between humans and the environment for a site that the Smithsonian Institute had previously considered for expansion. He urged them, Ismail said, to challenge traditional boundaries between humanity and nature.

“He told us to go out and come up with a museum that could challenge the way we see the world,” Ismail said.

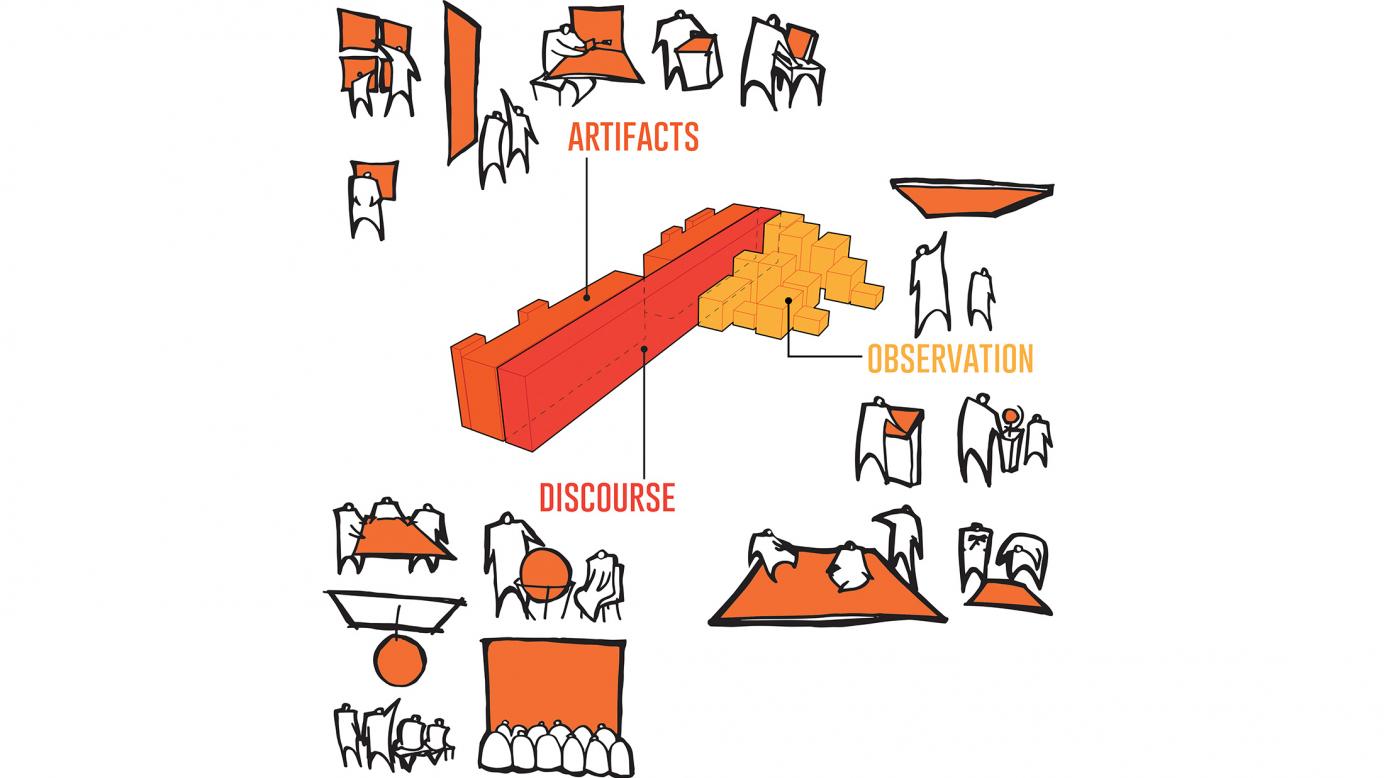

Ismail began researching world maps, thinking about them as artifacts showing how society has viewed the world. Ultimately, his answer to Li’s challenge was this museum, with a site plan designed as an abstract map of the National Mall, echoing the traffic and pedestrian patterns of that famous site.

Ismail divided his museum into three parts: a long spine housing maps and other artifacts showcasing past world views, modular observation areas where visitors use digital technology to observe the present world, and a middle space that he calls “discourse space.”

The discourse space offers views back into the interior of the museum as well as out into the city, prompting visitors to think about how what they have learned relates to their own present and future.