Most experts agree that sea-level rise will be a top threat to the commonwealth of Virginia in the coming decades, with the heavily populated Hampton Roads region facing some of the highest sea-level rise rates in the world.

The University of Virginia has created UVA Resilient Environment Seed Grants to promote interdisciplinary faculty research that addresses environmental challenges and helps develop more resilient communities that can anticipate, withstand and prevent threats from rising water.

“As a state institution, we have a particular obligation to engage in these issues that are a threat locally, nationally and globally,” said Phoebe Crisman, director of UVA’s Global Environments and Sustainability program, associate architecture professor and a grant recipient.

Architecture faculty members Alex Wall, left, and Phoebe Crisman, right, are leading research teams helping communities in the Hampton Roads area address and prepare for sea-level rise. (Photos by Dan Addison/University Communications)

Architecture faculty members Alex Wall, left, and Phoebe Crisman, right, are leading research teams helping communities in the Hampton Roads area address and prepare for sea-level rise. (Photos by Dan Addison/University Communications)

Crisman has spent 12 years working on various projects addressing coastal resilience in the Norfolk area, many of them in conjunction with the nonprofit Elizabeth River Project. The Elizabeth River and surrounding Hampton Roads area is experiencing the highest rate of sea-level rise along the entire East Coast, according to the World Resources Institute. Researchers project between 3 and 8 feet of sea-level rise over the next century, with land also sinking at a rate of 0.12 inches per year.

“It is a challenge of both land sinking and water rising, which is why it is particularly problematic,” Crisman said.

Threats to the Norfolk area – a nexus of transportation, shipping and military might – could severely impact the lives and livelihoods of its citizens. The Hampton Roads Planning District Commission predicts that, at minimum, sea-level rise will threaten more than 59,000 residents and $84.6 billion in existing assets.

Crisman, along with associate professor of urban and environmental planning Ellen Bassett and Mark White, an associate professor in the McIntire School of Commerce, received a UVA Resilient Environment Seed Grant to study resilient strategies for Norfolk’s Harbor Park, an industrial brownfield on the Elizabeth River with an interstate, a rail station and a minor league baseball park. Already, the UVA grant has spurred a related $498,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Architecture Professor of Practice Alex Wall also received a seed grant for research in nearby Portsmouth. He will work with Tanya Denckla-Cobb, the director of UVA’s Institute for Environmental Negotiation; associate engineering professor Jonathan Goodall; and associate environmental sciences professor Matthew Reidenbach to develop projections and recommendations that could help the city prepare for its share of sea-level rise.

Wall is working with Denckla-Cobb to meet with local stakeholders and begin discussions about relocation strategies for neighborhoods already at risk of repeated flooding. With Goodall and Reidenbach, he is considering a longer time frame of about 50 years.

“The time period that we are looking at is beyond what many politicians are thinking about,” Wall said of his work with Goodall and Reidenbach. “We want to provide a simple framework and an initial set of questions.”

In Norfolk and the wider Hampton Roads area, the need for such research is “incredibly urgent,” Crisman said.

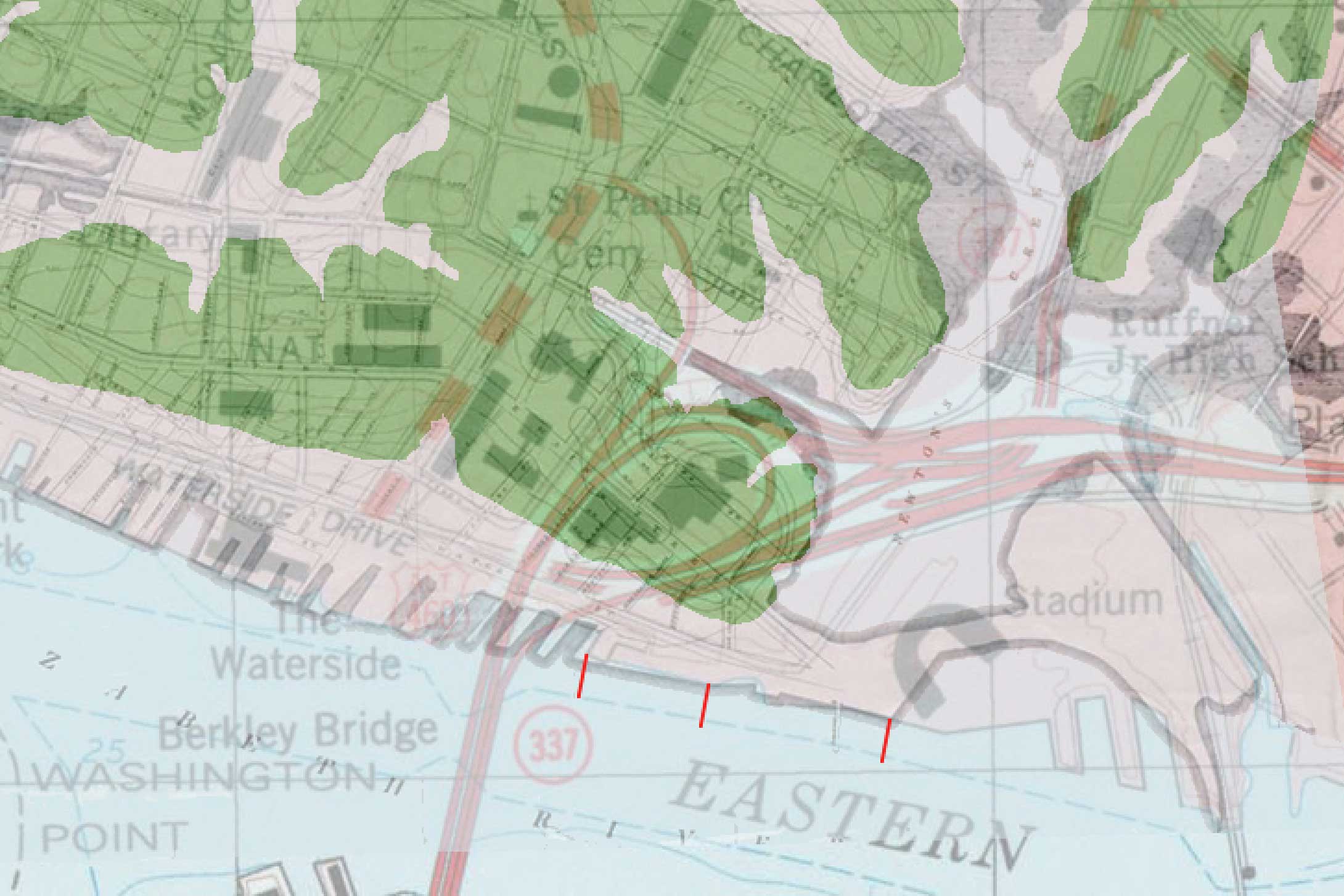

The Harbor Park site – like many other industrial sites along the East Coast – was originally water and wetland, but was filled in with debris and rubble as developers needed land for new railways or factories. Today, it is vulnerable to flooding and polluted from years of industrial use.

The above map shows areas around Harbor Park that were originally land – in green – and areas that used to be water but were filled in during industrial development – in gray. The gray areas are extremely vulnerable to flooding and sea-level rise.

The above map shows areas around Harbor Park that were originally land – in green – and areas that used to be water but were filled in during industrial development – in gray. The gray areas are extremely vulnerable to flooding and sea-level rise.

“Norfolk shares the same problem with cities like Boston and New York City, where there has been a lot of landfill of low-lying coastal areas over time,” Crisman said. “Not only are these areas going to flood, they are often contaminated land that will increasingly compromise water quality and ecosystems.”

Crisman’s architecture students have spent the last year developing a series of proposed solutions for the Harbor Park site, ranging from rehabilitating the land and creating wetlands to absorb water to building a series of walls and earthen berms protecting key sites like the railway and interstate. She hopes the site will serve as a test case for others in Virginia and nationwide. 2016 graduate Jenny Adair designed one example, shown at the beginning of this article.

“For me, the most effective strategies acknowledge areas that will flood and allow those areas to become wetlands or other repositories,” Crisman said. “Of course, there is a certain point where you need to stop the water in dense urban locations. So you do everything you can to mitigate flooding and develop multiple resilient lines of defense.”

For Portsmouth, Wall and his second-year Masters of Landscape Architecture students conducted similar research in the spring of 2015 and 2016, mapping out different flooding scenarios and solutions and studying successful strategies employed by flood-prone nations like the Netherlands.

“There has to be a transition from hard solutions to more dynamic negotiations with water,” he said. “[The Dutch] no longer build dikes to hold back the sea. Instead, they know where they will give up land and how they will give it up.”

Goodall is also looking at cyberphysical engineering solutions, with smart infrastructure that can redirect water automatically through a system of dikes and canals. Organizations like the Army Corps of Engineers are in the early stages of implementing these technologies.

“We want to imagine the future with these technologies in mind,” Wall said.

Turning Wall and Crisman’s research into tangible change will require extensive communication with policymakers and city planners. Crisman’s team, drawing on White’s expertise in corporate finance and sustainable business, is now conducting cost-benefit analyses of different plans, to better understand the economic ramifications.

“In order to implement innovative physical designs, we have to make the money work and get the policy in place,” Crisman said.

Crisman has also developed extensive resources for K-12 education to equip the next generation to solve these problems. In 2009, she created the “Learning Barge,” a 120-foot vessel designed as a floating environmental wetlands classroom for students of all ages. More recently, she has designed an environmental education center at Paradise Creek Nature Park in Portsmouth, where the Learning Barge can also dock, and worked with Portsmouth educators to make watershed education a required element of the city’s fourth-grade curriculum.

“If you want residents to truly understand the problems, you have to bring them to the water, where they can actually see the water level and understand where it has been and how it is rising,” Crisman said. “If people are going to commit to the kind of radical transformation that I think we will have to take on, fourth grade is not too early to start thinking about it.”

The $498,000 NOAA grant with the Elizabeth River Project and researchers from Old Dominion University is designated for additional K-12 education efforts in the Norfolk area, focused on helping students to understand the challenges of sea-level rise and envision solutions.

“The grants from UVA were really meant to be seed funding, and it has done exactly that,” Crisman said. “The work that our team put into that research has led to this additional nearly half-million-dollar grant, which is a great success story.”

Caroline Newman

University News Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today