I am happy to present the photographs of Alice Bailey. Being asked to be a part of The State’s Project opened my eyes to be on the lookout for photographers and an opportunity to make new friends. I happened to see one of Alice’s photogravure prints in a frame shop in Rapid City, South Dakota and was drawn to the dreamy feel of the photographs and the historical, labor-intensive printing process. Alice had just returned from several years in Alaska to her hometown of Rapid City, so the timing was right to include her Artic Entryseries.

Alice Bailey was raised in Rapid City, South Dakota, where she graduated from Central High School in 1999. She went on to receive a B.A. in Studio Art and a B.F.A. in Photography at the University of Virginia. Alice moved to Alaska in 2005 and spent the next eight years based in Fairbanks during the winter months and either in the Arctic or on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in the summers. She received her M.F.A. in Photography from the University of Alaska in 2014 and has taught art courses both in Alaska and at Colorado Mountain College. Alice recently completed an Artist Residency in Printmaking at Anderson Ranch Center in Snowmass Colorado. She now lives in Rapid City.

Arctic Entry

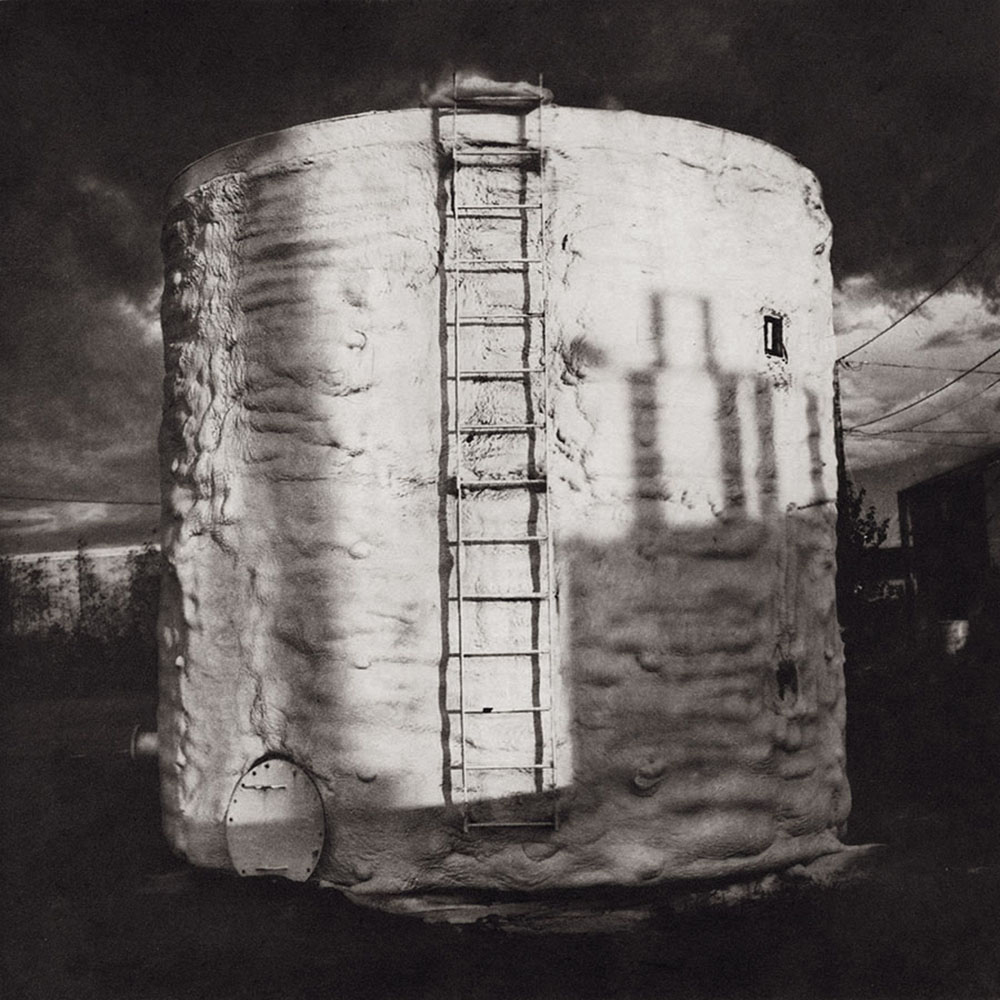

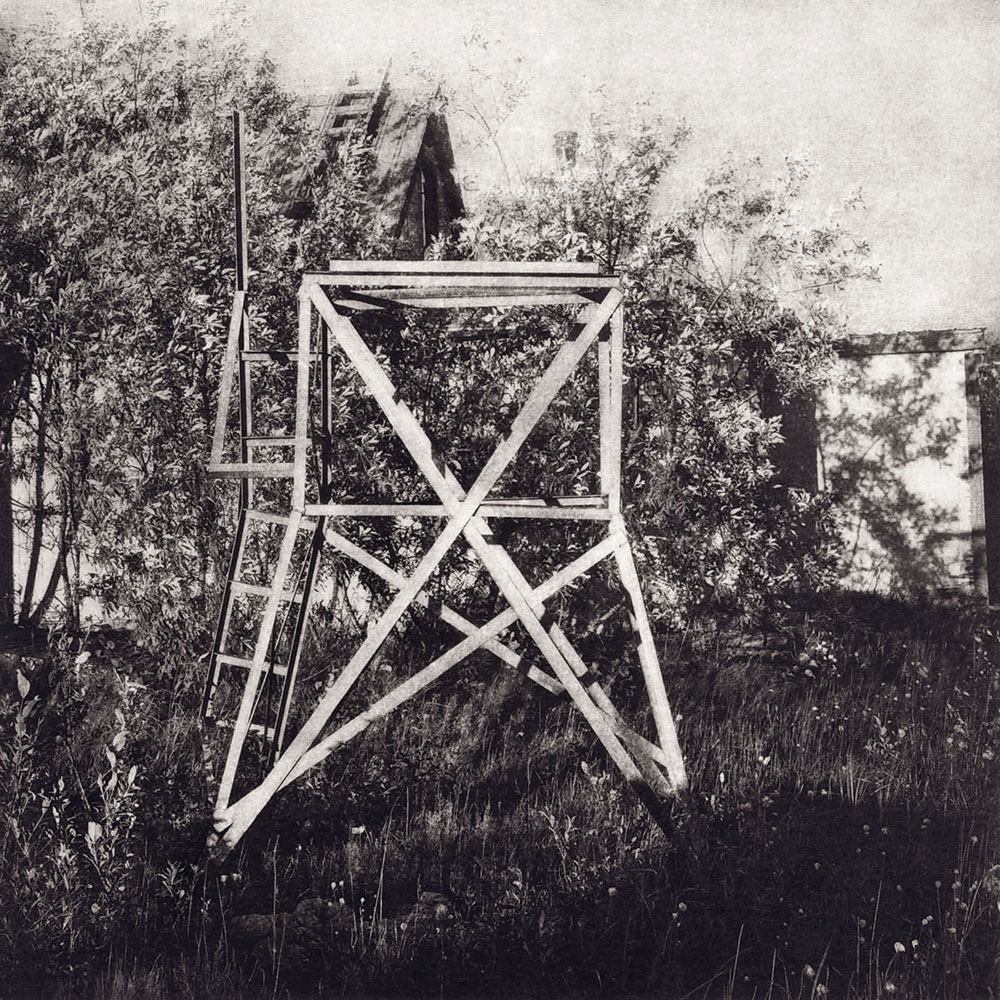

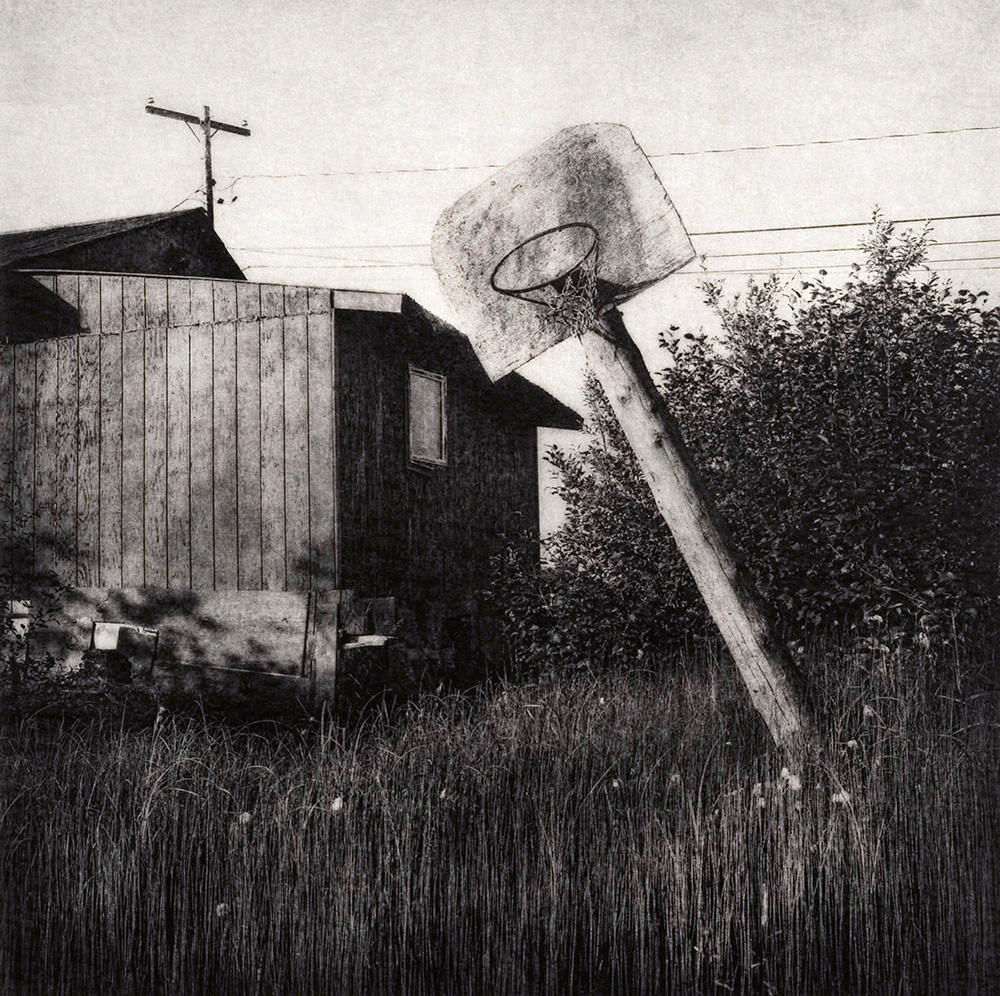

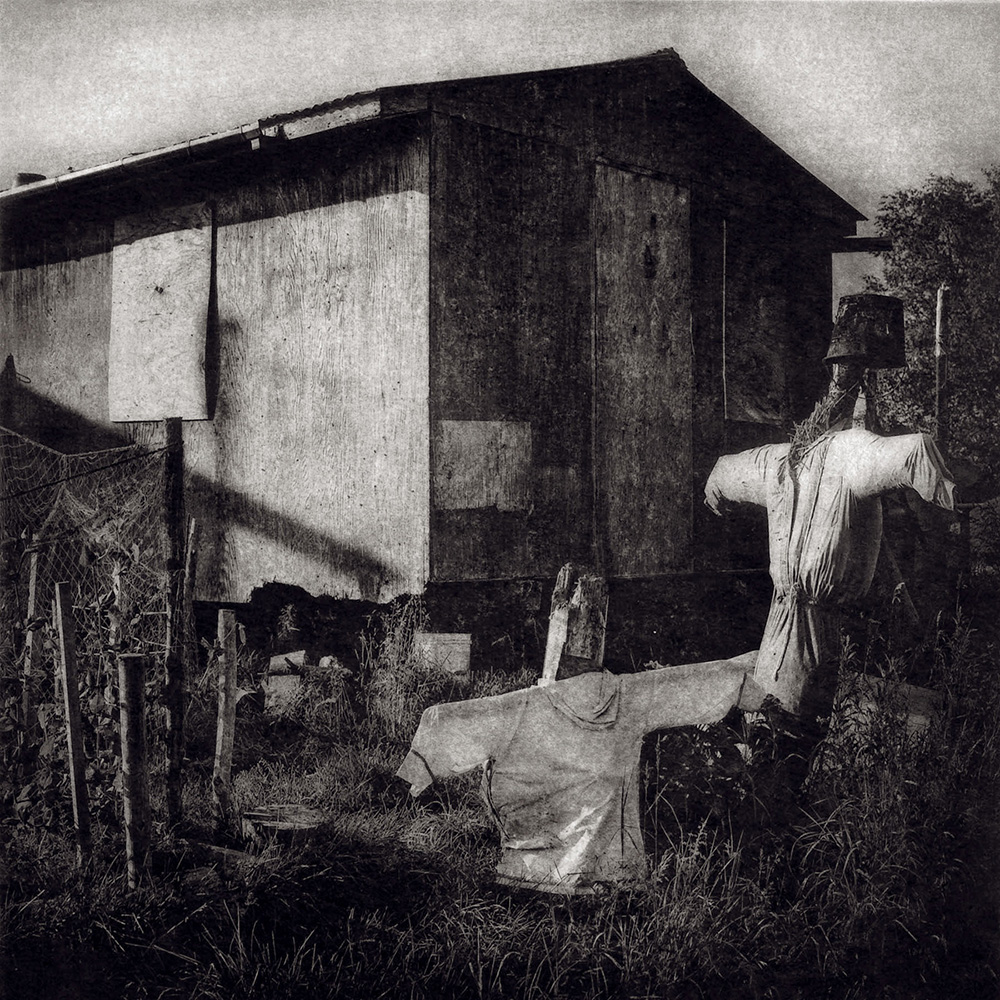

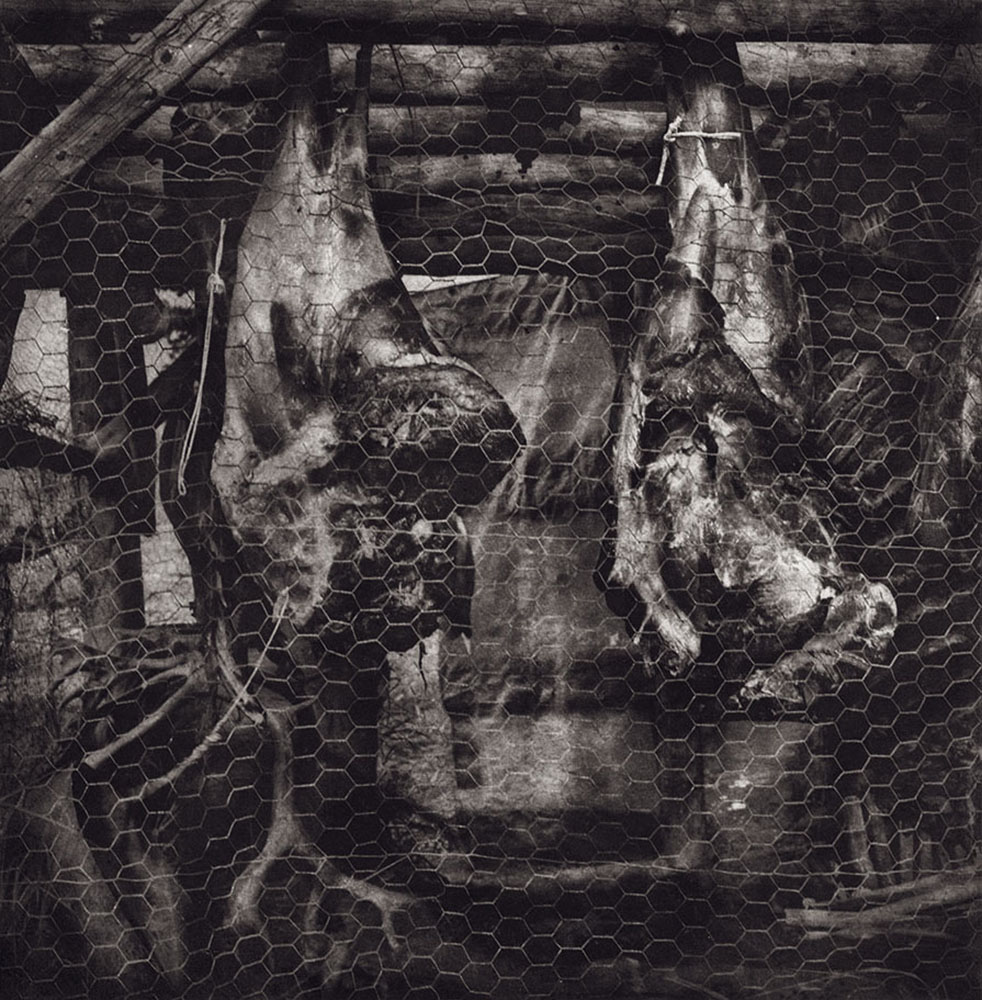

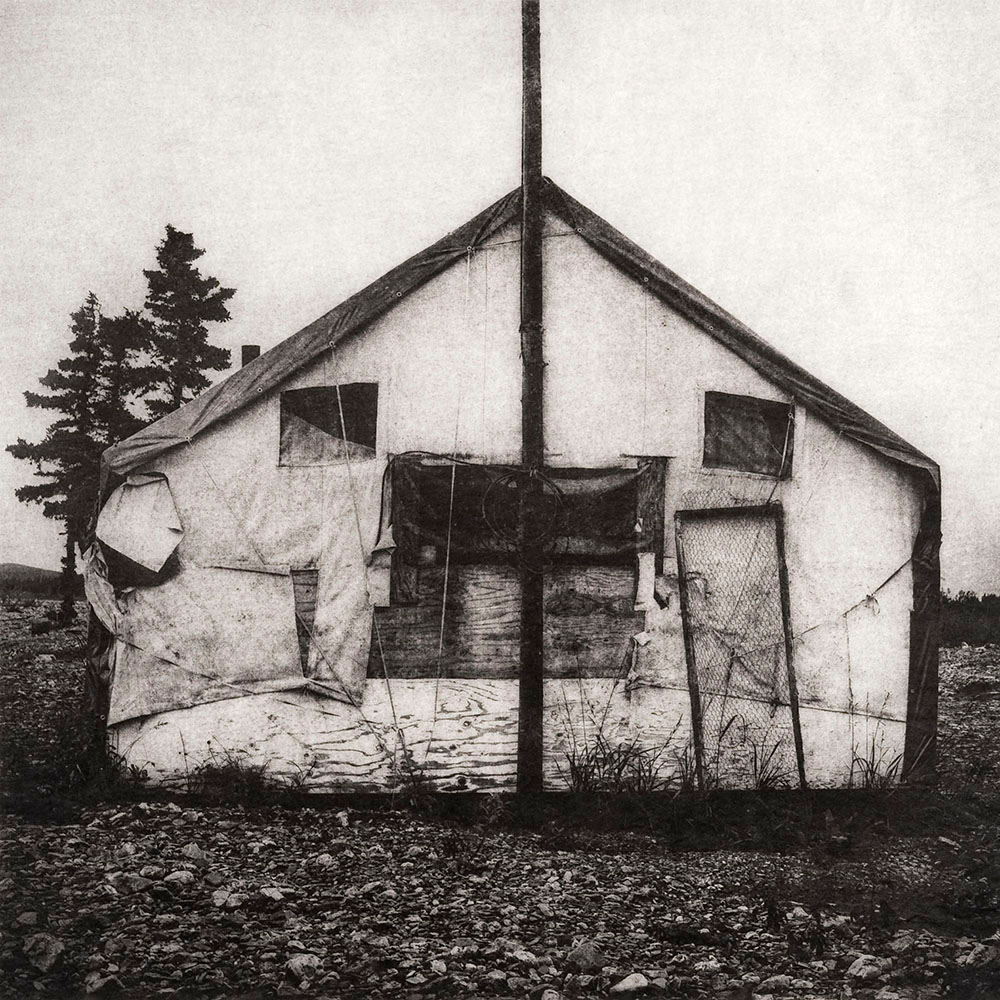

Alice Bailey uses her camera to capture the beauty that she finds in contemporary Western Alaska. Specifically, she is interested in how modern life on the Kuskokwim River exists as a montage of subsistence tradition, domestic life, industrial development, and the inevitable power of nature.

Arctic Entry refers to the outer entrance commonly built onto Alaskan dwellings, a buffer zone that increases insulation and provides storage for chest freezers, perishable food, outerwear, tanned hides, and freshly caught fish or meat. The arctic entry serves as a bridge between public and private life, as one must pass by these household items to knock on the inner door. Likewise, this series provides a portal through which life in one of the most remote places in the United States can be witnessed.

Photogravure is a 19th century process in which film negatives are enlarged, exposed onto sensitized paper, and transferred onto a copper plate. It is the same process that Edward Curtis and Alfred Stieglitz used to print fine art photography books in the early 20th century. After the image is permanently etched into the copper, highly pigmented ink is applied to the plate, hand-wiped, then printed with an intaglio press. The depth, delicacy, and texture made possible by the photogravure best captures the tactile and emotional richness of contemporary Yup’ik and Athabaskan subsistence culture.

What drew you to the project Arctic Entry?

After working and living in remote communities in Alaska, I grew to greatly respect the people and way of life there. Many people travel through these places and judge them based on superficiality; lack of running water (and “honey-buckets”), lack of well-stocked grocery stores, small homes made of weathered plywood or pre-fabricated housing, etc. However, I find the roughness of these structures beautiful in a way because they bear direct evidence of the environment, people’s creativity in constructing them with overpriced lumber, recycled materials, and my favorite, spray foam. To me this type of construction lends a unique sculptural quality to these objects.

I like your artist statement and how it describes the series as a literal and figurative ‘portal through which life in one of the remote places can be witnessed.’ Was it also a portal into the heritage of Yup’ik and Athabaskan cultures and how it is incorporated into modern life?

Yes, my enjoyment and respect for Yup’ik and Athabaskan culture was underlying the entire project. The warmth and generosity of the people that I know in these communities made me feel comfortable making photographs there. A majority of the images are of my friends’ homes and nearby areas. For instance, “Dancing Pants” is an image I took outside of my friend Sarah Brown’s house, as she was teasing me from inside the window at how fascinated I was with her laundry drying in the wind. As far as modernity, I made a point not to avoid nostalgia. I want to portray daily life as it actually is, and the interesting part is how tradition, resilience, and modernity remain inseparable.

Did this series lead to your Fairbanks Portraits or visa versa?

I started the Fairbanks Portraits series during the winter months when I was back in interior Alaska. Again, my personal connection to the subject matter inspired the project. Fairbanks is another place where beauty often lies beneath the surface. As a resident myself, I understood why people stayed there despite extreme temperatures and darkness during the winter months. Fishing, running dog teams, and walking in snow for seven months a year is a regular part of life in Fairbanks, and the soft northern light made retaining detail on my negatives much easier. I hoped to incorporate each individual’s personal environment in their portrait as part of their narrative. This series is still in progress. I also hope to start another series of portraits of elders in Western Alaska, as well.

The Arctic Entry images are beautifully printed with the photogravure process. Why did you choose this process? Where did you learn the process?

I thought a printing method with more physicality was more appropriate to these images, both because the images are of sculptural objects and to speak to the cultural richness behind them. I was convinced that photogravure was perfect when I saw the delicacy and uniqueness of Edward Curtis’s North American Indian Volume XX at the Museum of the North at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. I knew that the process had not changed much since the first fine art photography was printed with it in the late nineteenth century, and that I would have to find a master printer to learn it from. In 2011, I learned the process from Lothar Osterburg at Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Snowmass, Colorado. After I returned to Alaska, I adjusted the chemistry to the dry and cold climate and continued making plates. In 2014, I traveled to New York City to learn more from Osterburg. I continue to enjoy and explore the technicalities of photogravure.

Now that you are back in South Dakota, will you be incorporating the photogravure or other historical processes in current or future photography projects?

I have all of the chemistry with me and I would love to continue using photogravure here, as well as explore other methods of printing photographs, including some intaglio printmaking methods. I plan to make new landscape and possibly portrait images here, as I have missed our unique prairie landscape and the Badlands while I’ve been away.

Do you miss being in Alaska and the wildness and remoteness of it? Did you feel that remoteness was conducive to producing more work?

There is a saying in Alaska that one can leave Alaska, but Alaska never leaves you. In other words, I think about Alaska every day and hope to visit as soon as possible to see my dear friends and continue making photographs there. The remoteness of the state is why I initially moved there, and the people are why I endured so many long winters and stayed.

What was life like on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and in the Arctic? Were you settled in to one place or roaming about doing your photography?

My first experience with living on the Upper Yukon River was as a dog handler for Patrick and Courtney Moore in Tanana. Afterwards, I was hired as a Fisheries Technician for four month field seasons at Pilot Station on the Lower Yukon River, where we fished for and operated sonar imagery of daily salmon passages. On the Kuskokwim River, just south of the Yukon River, I visited over 20 communities conducting subsistence salmon surveys for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Each of these experiences taught me of the importance of the subsistence lifestyle essential to survival even today. My photography moved with me as I traveled to different communities. The Arctic Entry images were taken at a remote Athabaskan hunting camp at the headwaters, in Bethel, the largest community, and at the mouth of the Kuskokwim River, spanning hundreds of miles.

Jean Laughton

Original Publication – Lenscratch