In the Athens, Georgia, of the 1980s, live music was like oxygen – it stimulated people, sustained them and it was everywhere. Musicians and their friends and fans congregated in small clubs, practice spaces and house parties and the sound ebbed and flowed, like the life blood of a popular culture that was poised to overflow its crucible.

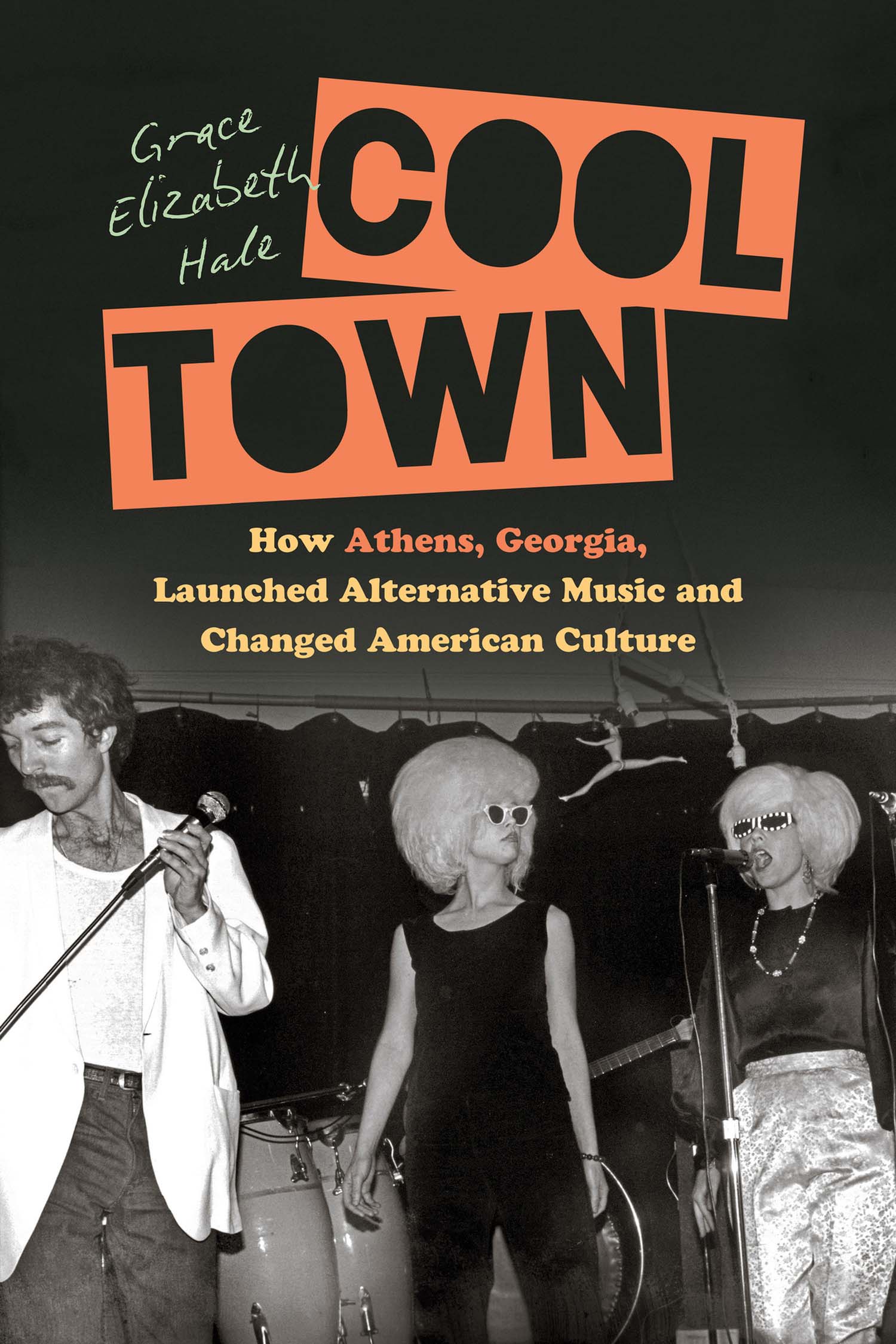

In a new book, University of Virginia history professor Grace Hale has returned to the Athens of 35 years ago, where the local music scene gave birth to such popular acts as The B-52s, R.E.M. and the Drive-By Truckers.

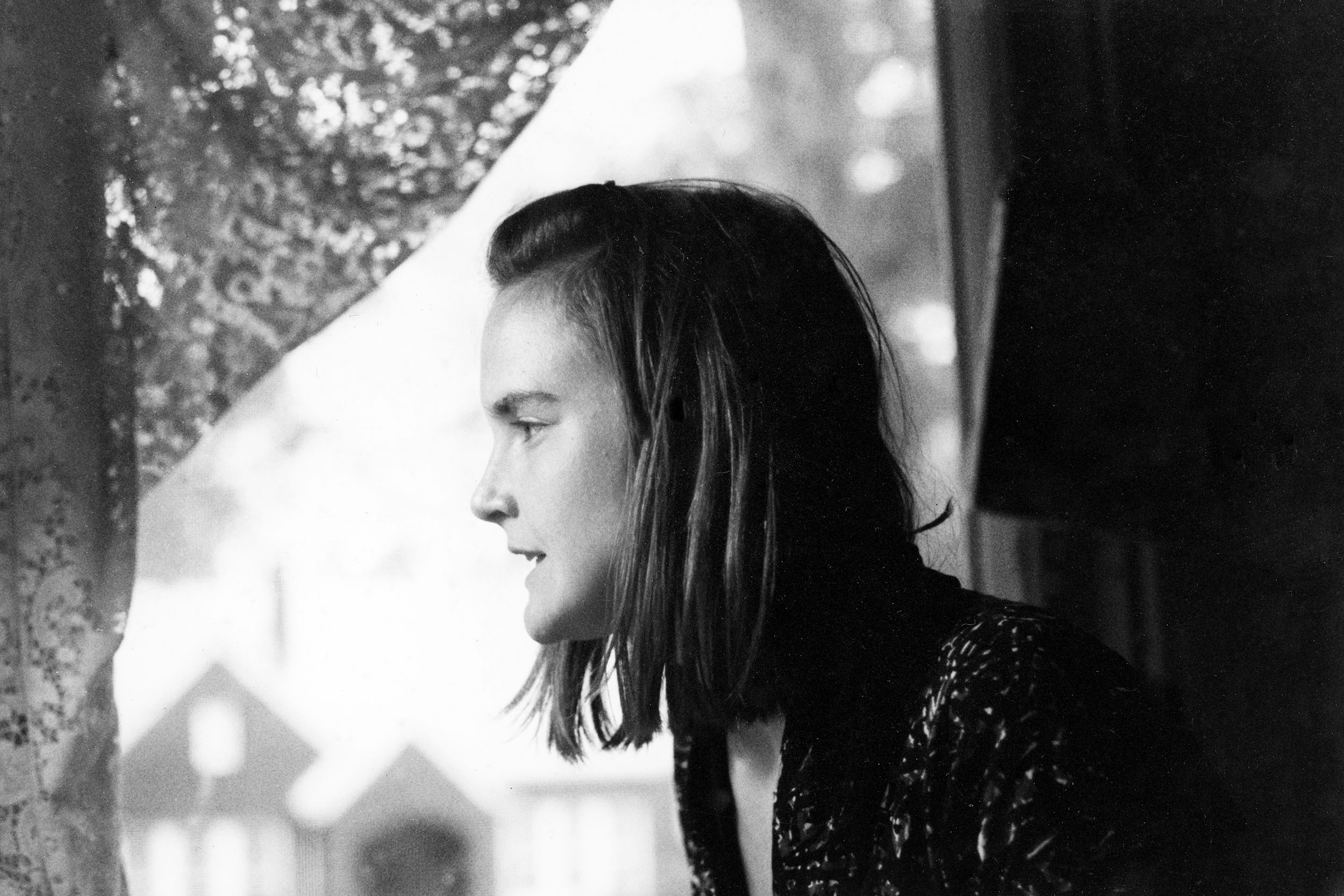

Hale was a part of the scene in Athens in the ’80s and knew the players. She moved to Athens in 1982 to attend the University of Georgia, enrolling as a business student. By 1987, she had co-founded The Downstairs café, coffee shop and music club with David Levitt, and they were in a band, Cordy Lon, together.

She has revisited this time of her history in her book, “Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture.” Her book is part scene history and part music criticism.

“About half the book is about a time when I am not involved in the story,” she said. “The hardest part of writing the book was developing the right voice, a voice that can go back and forth between first person and a more objective, third-person form of narrative. It was a writing challenge, figuring out to make those shifts and how much to put in that was personal.”

Hale was initially reluctant to write the book, because as part of the story, she worried about perspective.

“I wanted someone else to write it, but that somebody never seemed to appear,” she said. “There are writing challenges I had never faced as a historian, because when you work as a historian, you don’t write about yourself. That was a challenge to get over at the level of the writing and at a deeper conceptual level, but I think that in the end my direct connection actually helps to bring people into the larger story.”

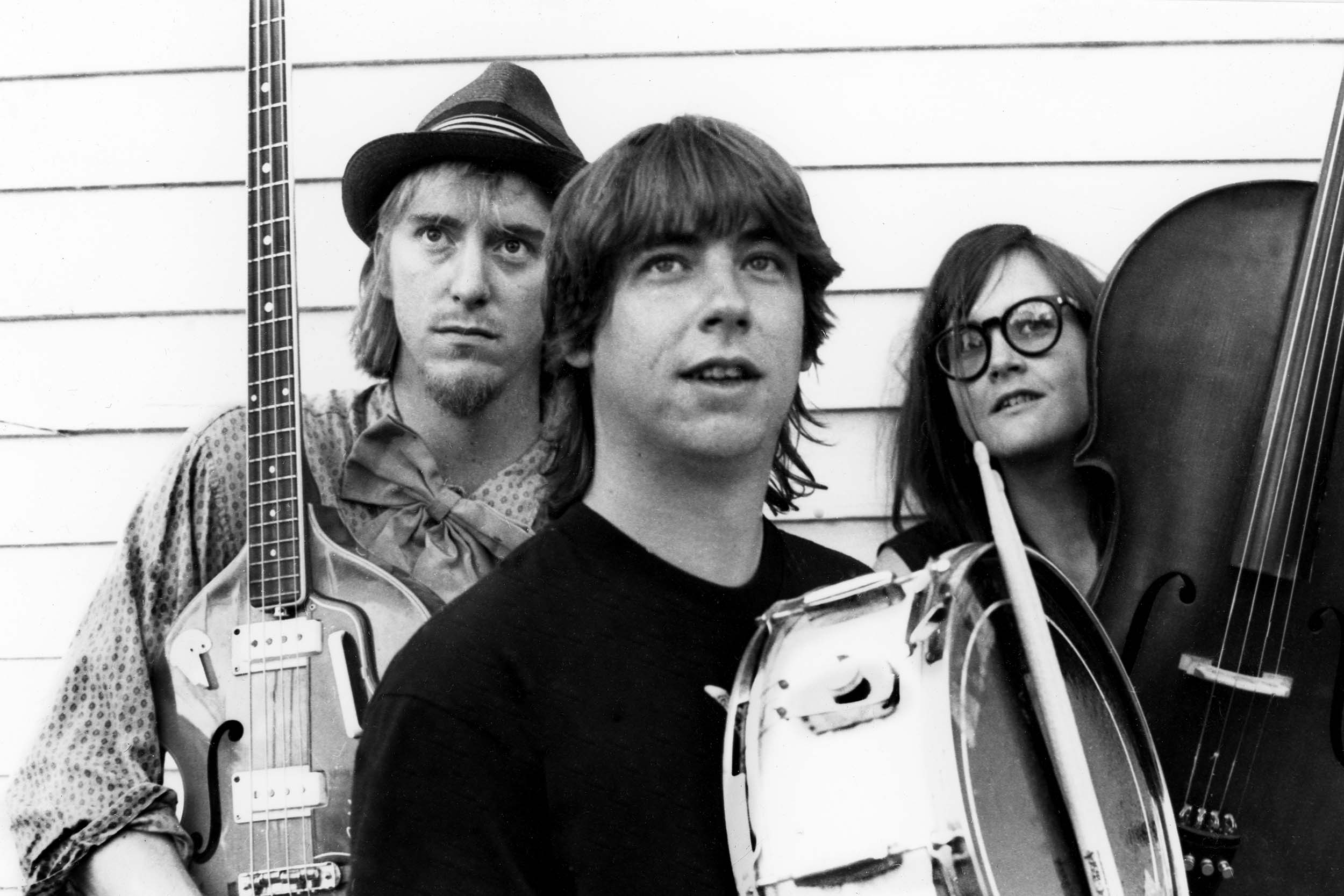

And that story included her friend Vic Chestnutt, a singer-songwriter who had also been part of the Athens scene until his death in 2009.

“I kept thinking somebody else would do it, would interview all of these people, because there is a really important story here to tell,” she said. “But Vic’s death made me realize that people weren’t going to be around to interview and I needed to get started.”

Hale began by interviewing people she knew and then reaching out to their contacts. She also dug into back issues of local publications for concert schedules and music reviews, as well as privately held materials including recordings, photographs, press clippings and band flyers. At times, she purchased important materials on websites such as Ebay. The research took years because there was no official archive, although the hometown University of Georgia is now actively collecting these kinds of materials.

“People’s memories are right about what it felt like, and what the tone was, and what the takeaway was for their experience, and you get some great stories and some great insights that way,” Hale said, “but often our memories are wrong about particularities. Like the date that you thought you saw this band at that club, and it was actually another, or who opened for that band on that night actually wasn’t the one that you remembered. So much time had passed that I had an ability to come back to that material with a more critical eye – or at least with the sense that I needed to check what I remembered with other sources.”

But Hale’s personal involvement gave her entrée into other aspects of the story.

“Because I had been there, I had a sense of what the important stories were, such as figures that the larger world never knew about,” she said. “They never got ‘famous’ in some larger way, but they were key figures in terms of the myth or the reality of the place. That gave me a starting point that I think would be hard to have if you did not have some direct experience.

“Having an understanding of what is going on in the larger world and how the local and the particular might connect to larger themes that are important – being a historian is helpful there,” she said. “‘Cool Town’ is an attempt to think seriously about what alternative cultures can do, in a way that is actually interesting for anyone who loves indie music to read.”

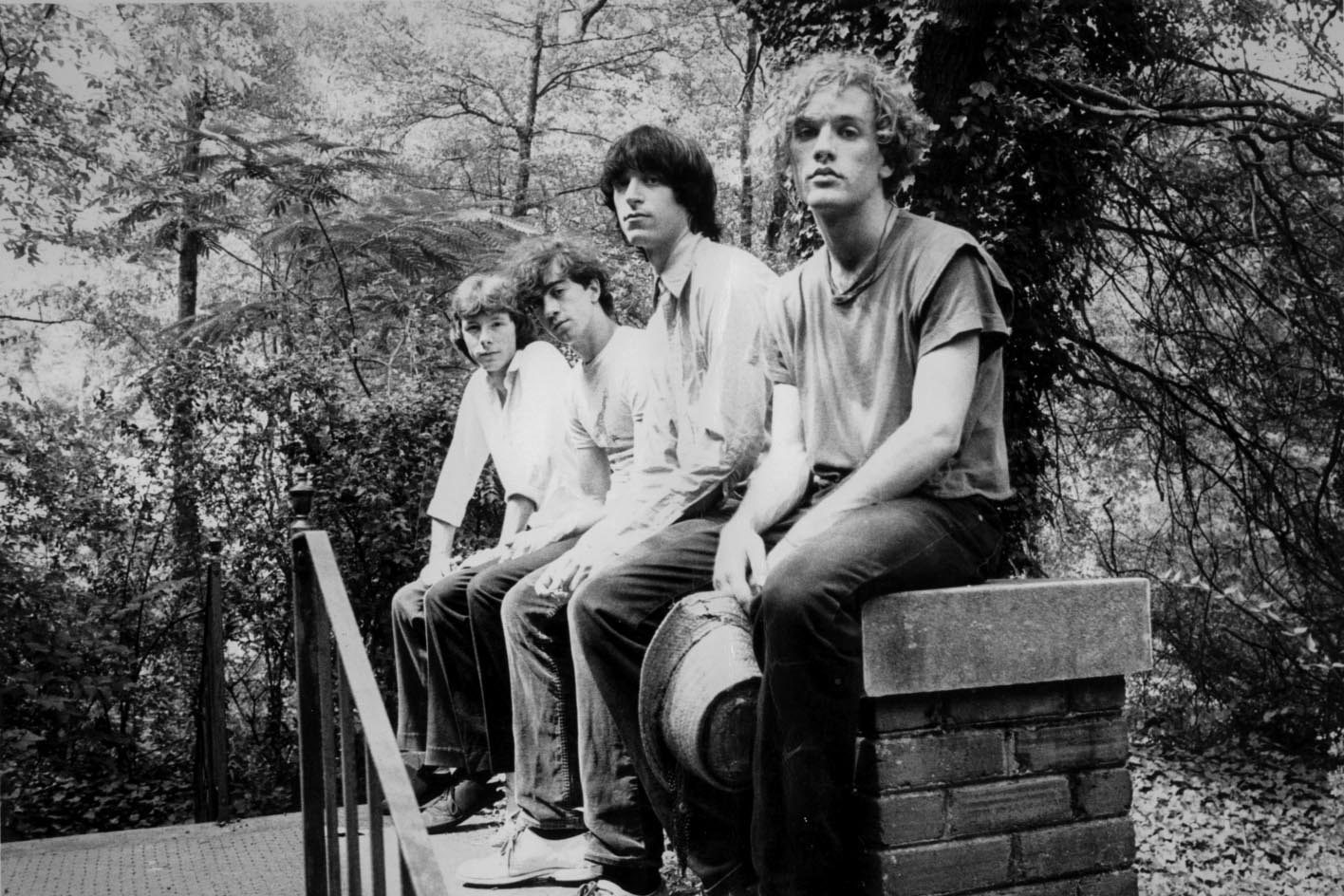

The Athens scene was a combination of ingredients – key people in the right places at the right times who came out of a university town, where young people could live cheaply and had access to the cultural resources available for free in those pre-internet days at a large, public university, including music libraries, film libraries and old magazines.

“A few key individuals came along and decided to stay in town and not move to New York, and that made Athens different,” Hale said. “Without having the amazing folks in The B-52s, you don’t have Athens; without Ricky Wilson and Keith Strickland [two founders of The B-52s] there is no Athens scene. But they can’t really make it there as a band in the late 1970s because there is a not an infrastructure yet.

“At the same time, people in town like Jerry Ayers, a close friend Wilson and Strickland met when they were still in high school, was hugely influential on them. He had been a part of Andy Warhol’s Factory, and after living in New York City for a while in the 1970s, he came back to live in Athens until he died a few years ago. Jerry, later Jeremy, Ayers mentored wave after wave of people who participated in the Athens scene over the decades.”

And while The B-52s eventually chose to leave Athens to pursue their career, other bands that came after them, like Pylon, made the choice to stay and remain rooted in the local creative community that they had helped create.

“That is as important as The B-52s, because that creates a pattern for how people are going to stay in town and make music,” Hale said. “It seems like once a decade, the scene boils up again and you have the [musical collective] Elephant Six bands like Neutral Milk Hotel or the Drive-By Truckers, bands that come out of Athens and become important in the larger world.”

While music was a large part of the Athens scene, it was not limited to that. Scene participants opened clubs, restaurants, art galleries and recording studios, and people worked as writers, painters and performance artists. Hale herself was a part of the Athens scene as a member of a band and the co-owner and founder of a small café, gallery and music club. One of the things Hale loved about writing the book was that she learned new things about Athens.

“I interviewed more than 50 people, and I realized I did not understand just how many incredibly creative, thoughtful and interesting people lived in this small place in the 1980s,” she said. “It was a special place.

“Many of us in Athens had no idea what the possibilities of life were, and we were able to find answers to those questions through our participation in the Athens scene,” she said, “whether it was a desire to be an artist, how music might function in your life, how you were going to think about community and your connections with other people, how you were going to live in the world.

“I think the scene created a place where people could think about and were encouraged and almost required to think about all of these things. The way the scene worked made people question things and learn to think for themselves. That opened the eyes of a lot of people who had grown up in the suburban and small-town South to a sense that there were other possibilities for life.”

As a historian, Hale said it is important to think about the relationship between popular culture, art and politics in context, in particular times and places.

“What are the conditions that provide a way for people to find deeper meaning and things to commit themselves to?” she said. “What makes people feel like they are alive within the stream of time, that they are making history? We need a historical understanding of times and places in which a sense of possibility is palpable.”

“I started going back to grad school part-time while I was running The Downstairs,” she said. “I guess I didn’t think I was busy enough.”

She started working on her master’s degree in history and decided she wanted to be a college professor because being paid to read, write and think seemed like a great life.

She left Athens in 1991 to start a Ph.D. program at Rutgers University in cultural history and women’s history. After graduating from Rutgers, she held a postdoctoral fellowship at Emory University in Atlanta and taught at the University of Missouri for a year before coming to UVA in 1997.

“The history department is really great at the University of Virginia, and I felt lucky to be here,” she said. “I also had the opportunity at UVA to work to create American studies as an independent program and now department.”

Hale has written other books, including “Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940” and “A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle-Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America.”

She had the Athens book in her for a while, though she was not fully aware of it. She was reminded of this by a North Georgia College history professor, whom she first met when he was a UGA graduate student.

“He reminded me that I took him on a tour of Athens and I showed him the music history sites,” she said. “His UGA adviser, a historian who was also a friend of mine, said, ‘She’s going to write a book about this one day.’“That was in the year 2000, and I have to say that was the farthest thing from my mind then. My friend ended up being right.”