It was not uncommon for 15th- and 16th-century European explorers in the New World to capture native peoples to serve as translators and guides, and Paquiquineo, an Algonquian whom the Spanish picked up somewhere along the Chesapeake coast, found himself in such a situation.

What he ended up doing to change his fate challenges the very foundation of what we know about the settlement of America.

Paquiquineo – whom his captors baptized Don Luis de Velasco – traveled with Spanish explorers and missionaries to and from Spain, through New World areas that became Florida, Mexico and Cuba, and even further. After almost 10 years of this life, in 1570 he took a group of Jesuits to found a settlement near Ajacán, where he said he came from originally, on the East Coast of North America in what would become Virginia.

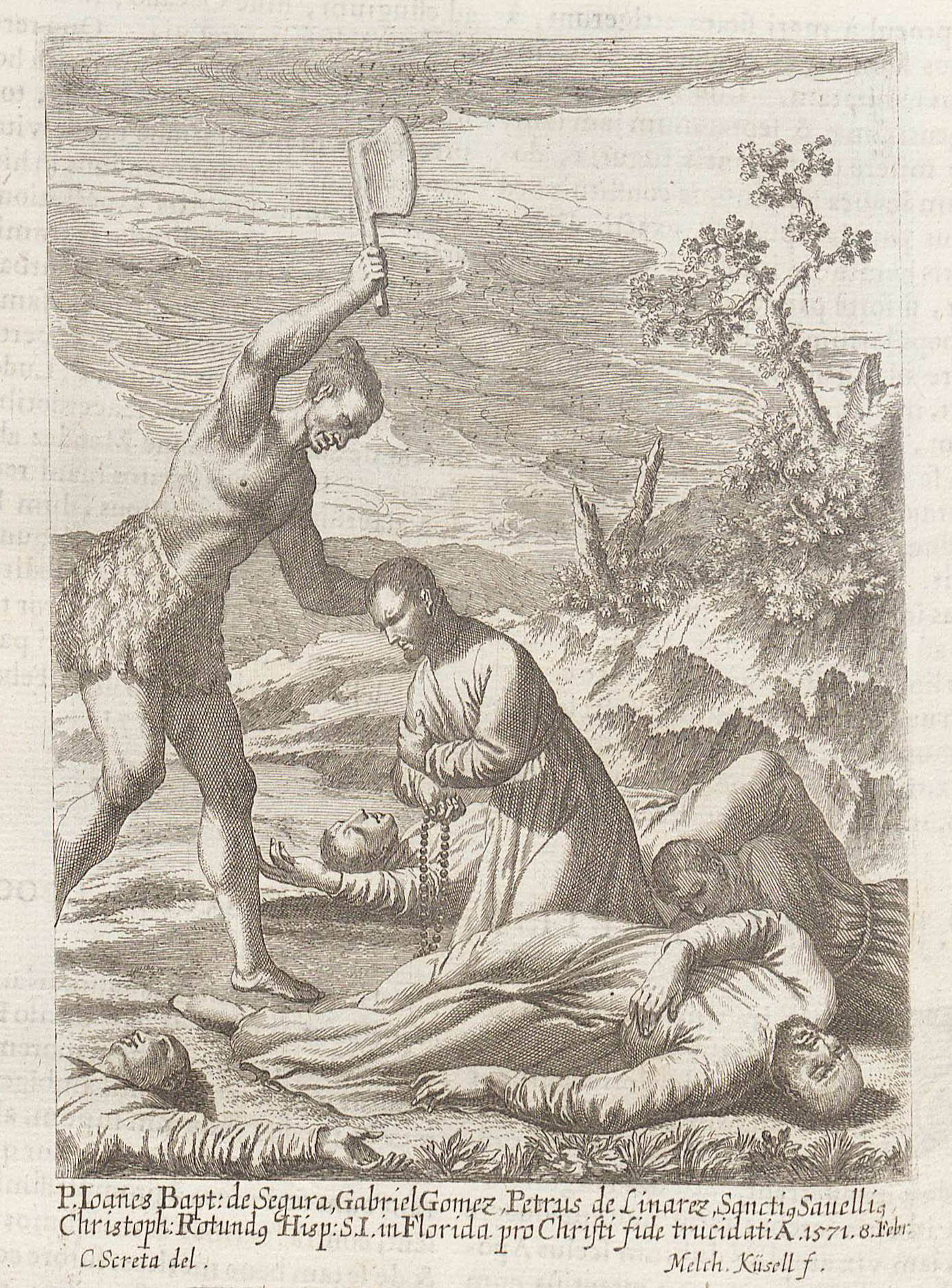

A year later, however, he led an uprising that destroyed the colony and killed all the Jesuit priests.

What happened to Don Luis?

University of Virginia English professor Anna Brickhouse kept seeing his name appear in the early American literature and documents she was studying for a project on Jamestown. She became so intrigued, she switched her project to find out everything she could about this man, including a satirical novel written about him in the 20th century. In the process, she has introduced a new way of analyzing literature working from the premise that native interpreters were often using translation – and mistranslation – to protect the sovereign interests of the inhabitants living in the Americas when Europeans arrived, starting with Columbus.

Brickhouse, who earned her B.A. at UVA in English and French, will pick up a prestigious award for “The Unsettlement of America” this Saturday when the Modern Language Association presents to her its 46th annual James Russell Lowell Prize at the association’s convention in Austin. The book also was a co-winner for the Early American Literature Award.

“Brickhouse demonstrates that the motivated mistranslation practiced by native informants allowed them to pursue unsettlingly sophisticated political agendas, which were based on their shared knowledge of the devastating consequences of colonialism,” says the association’s announcement of the award-winning study.

Don Luis “spent almost 10 years in European civilization,” Brickhouse said. “He had seen so much of the world, more than many European colonists. He had the long view of what colonialism meant for native peoples. He was not just defending his home out of a basic mistrust of strange people with a different culture; he was bilingual and assimilated, and he made an informed choice against European settlement,” she said.

Jesuit records recount Don Luis’ violent murder of the Jesuits and annihilation of the village, or act of “unsettlement,” from the testimony of one surviving witness, a youth named Alonso. Although the Spanish retaliated against the Indians in the area a few years later, they never found the one who turned against them.

Brickhouse did find a later account from the area of Florida where a traveler wrote about encountering the leader of a group of Indians who spoke fluent Spanish and called himself Don Luis. Could this have been the same Don Luis who acted decisively against settlement in Ajacán? Whether or not he was, his name and story were circulating widely in early modern Spanish writing.

The history of early Spanish exploration and conquest became important culturally and legally as English settlers became established in Virginia and the U.S. expanded in the 19th century. Later, when tribal territories were being set up and land allotted to settlers moving west, federal reports of early encounters were used to claim territorial possession. The evidence of a Spanish settlement in what would later become Virginia was deliberately suppressed in the mid-19th century, Brickhouse argues, because it complicated both international and especially American Indian law, which was based on the legal premise of an English “first discovery” of Virginia.

Brickhouse examined several other narratives and retellings of native-European encounters, including that of John Smith and Pocahontas, for example. Even the stories that depict native people helping the English colonists often contain with them other versions of the same events, or unsettling details that contradict the most prevalent narratives about the settling of Jamestown and Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Misunderstandings abounded between indigenous people and missionaries and colonizers, who in their writings showed more anxiety and confusion about their captive translators than has generally been passed down. Through what she calls “motivated mistranslation,” it appears that the native interpreters found ways of thwarting early settlement efforts.

“The bicultural, hybridized frameworks of knowledge within which Don Luis and Alonso acted and narrated in the 16th century cannot be fully excavated or transparently understood from inside the perspective of Western modernity, or through its forms of knowledge alone,” writes Brickhouse, who also directs UVA’s American Studies program.

In researching the book, Brickhouse examined a variety of early modern texts in English and Spanish, reading them not as a historian might, but instead with the tools of a literary scholar who is trained to see competing narrators and stories within stories. In the process, she realized that early American literary history tends to be organized around “successful” settlements – those that lasted in the New World.

But there is an alternative narrative that might be organized around instances of “unsettlement” – around failed and lost colonies, and around the agency and knowledge of indigenous people who foiled European attempts at conquest. Brickhouse reveals a more complicated scenario than what most Americans learn in school, one that includes Spanish colonial origins in the very place – Virginia – where we have been taught to assume British colonial origins.

This Spanish colonial priority in what would become Virginia came about and then ended swiftly precisely because of Don Luis and his ability to shape a story about his homeland in Ajacán, Brickhouse said. Colonial records show that he first told stories of an opulent place that would entice the Spanish to restore him to Ajacán as an interpreter, but once there he began to alter the narrative to make his homeland less desirable, casting it as a place of famine and death in the records that Spaniards passed on. He ensured that after he had destroyed the early Spanish settlement, the record left behind would contain nothing to invite future attempts – until three decades later when the English, who had no access to the Spanish records, came and formed their precarious settlement at Jamestown.

“Reading between the lines of historical documents,” the MLA award says, “she challenges us to reconsider the power of language as used by the colonized to resist the very forces that have shaped the archive and the ways we understand it.”

Anne E. Bromley

UVA Today Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication – UVA Today