Written by: Katie McNally

In honor of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death and in anticipation of the rare First Folio edition it will host in October, UVA’s Special Collections Library has created a new exhibit that looks at the strange and wonderful history of Shakespeare in print.

While short on soothsayers and vengeful Brutuses, the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library still offers a rare glimpse into the works of England’s most famous bard.

Its new exhibit, “Shakespeare by the Book: Four Centuries of Printing, Editing and Publishing,” takes visitors through the many ways Shakespeare’s work has been shaped and interpreted over the centuries.

UVA is among 52 institutions nationwide chosen to host one of the Folger Shakespeare Library’s rare First Folio editions of the Bard’s plays this fall. The folios are touring the country to mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and the new Special Collections exhibit was created in anticipation of its arrival.

The idea of publishing Shakespeare’s collected plays in books like the First Folio did not arise until several years after his death. The playwright himself had no role in formulating what would become the “official” versions of his works and as a result, the history of publishing Shakespeare is also a study in the evolution of editing.

“That is really interesting to us at UVA because the University has been involved in some big innovations in editing over the last century, particularly in relation to Shakespeare,” Special Collections curator Molly Schwartzburg said. “Since the late 1930s, the University has been a leader in editorial practice and more broadly, the study of the book.”

All photos by Sanjay Suchak unless otherwise noted.

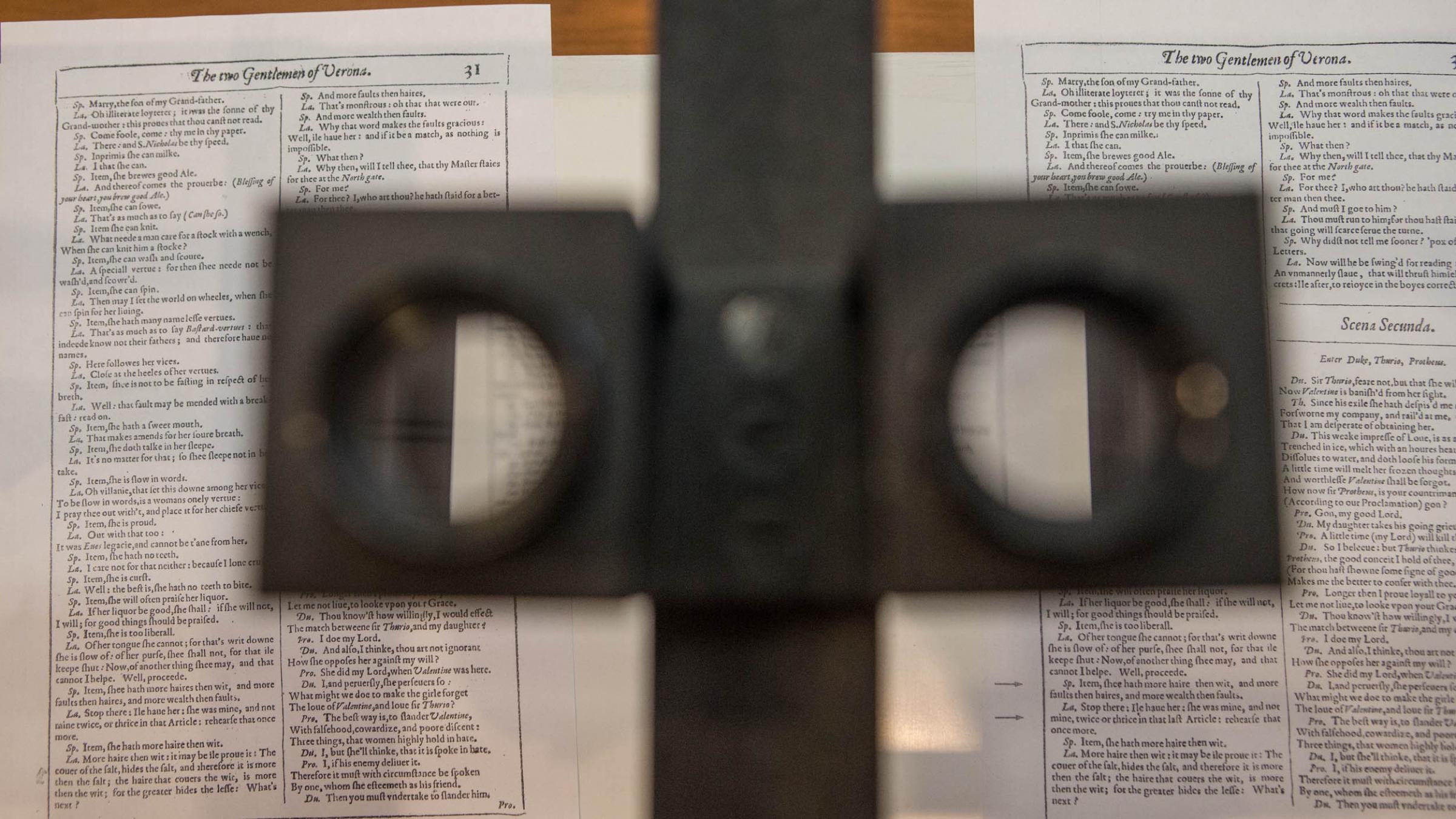

The Hinman Collator, created in 1954 by UVA graduate Charlton Hinman, revolutionized the way the edited works of Shakespeare and many other prolific writers are studied. Hinman was the first graduate student of UVA’s influential English professor and innovator in bibliographical studies, Fredson Bowers.

Before Hinman completed his degree, he and Bowers served together in a U.S. military cryptology unit during World War II, and that’s where Hinman got the idea for the collator, which compares different editions of the same work to identify small differences. Using a complex system of mirrors, the collator overlays the same page from two different copies of a work of literature. As each eye looks at a separate page, the brain translates them into a single image and discrepancies in the two copies stand out.

After completing his design, Hinman used the collator to determine the order of printing for every copy of every page of the 55 examples of the First Folio housed at the Folger. This allowed him to select the “best” version of every page for a massive facsimile edition.

“Decades after his death, Charlton Hinman’s machine is still hugely influential and libraries all over the country still have working Hinman collators,” Schwartzburg said.

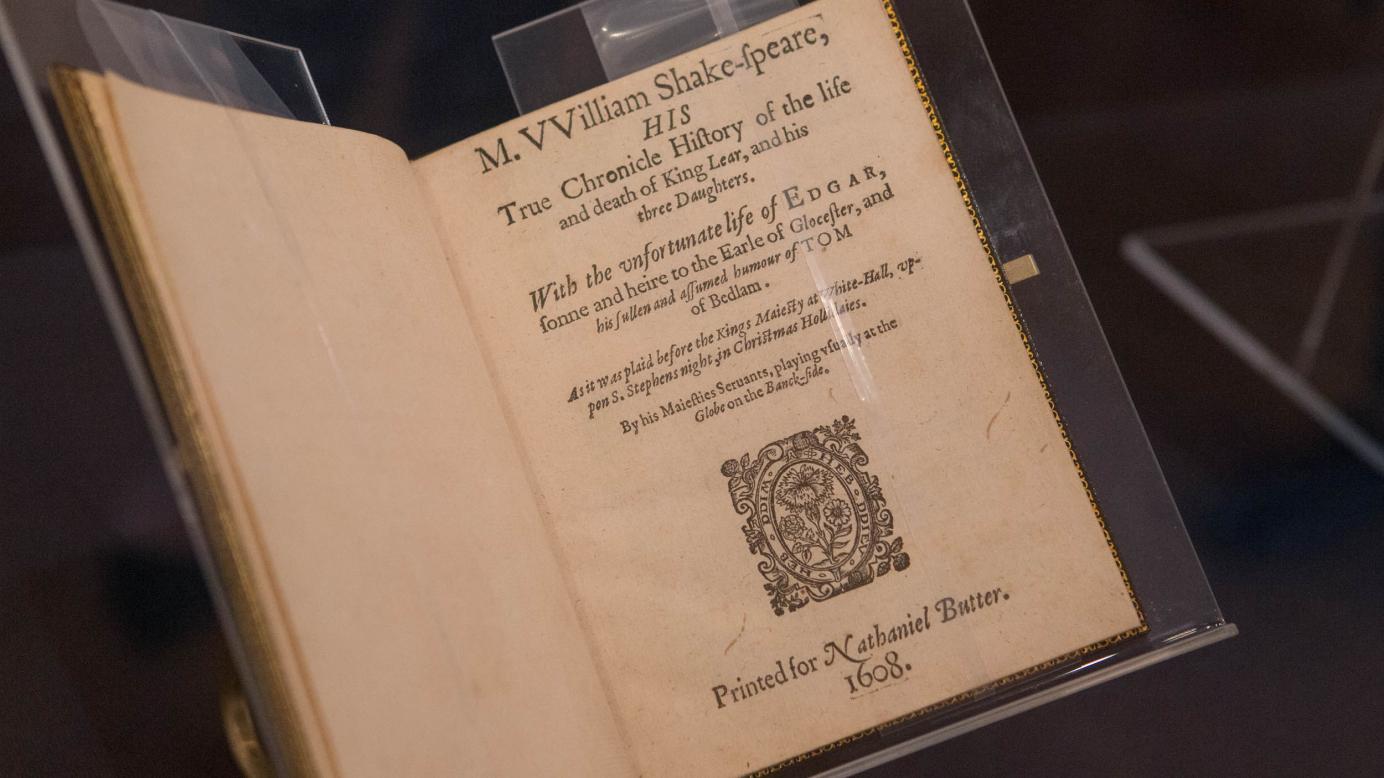

Hundreds of years before Bowers and Hinman, the first men to publish Shakespeare’s collected works unintentionally became its first editors. The second quarto of “King Lear,” printed by William Jaggard for Thomas Pavier, is the earliest Shakespeare item in UVA’s collection.

This quarto was once part of a complete set of separately bound plays that is often called the “false quarto” because it was actually printed in 1619, despite the 1608 date listed on each quarto’s title page. Jaggard and Pavier were the first to offer them all together as a set, and thus the first to decide what items should be included when printing the first collected edition of Shakespeare.

Pages from UVA’s library catalogue indicate that the University once owned a complete set of the Pavier Quartos. This first collected edition – which predates the First Folio by four years – was donated to UVA in 1853 by Thomas Jefferson’s son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph Jr.

Unfortunately, the entire set was lost when the Rotunda burned in 1895.

“It would have been a treasure if we still had this,” Schwartzburg said. “They’re extremely rare as complete sets.”

For reference, there are approximately 230 First Folios still in existence, but there are thought to be only four or five complete sets remaining of the Pavier Quartos. (Photo from the Holsinger Collection, UVA Special Collections Library.)

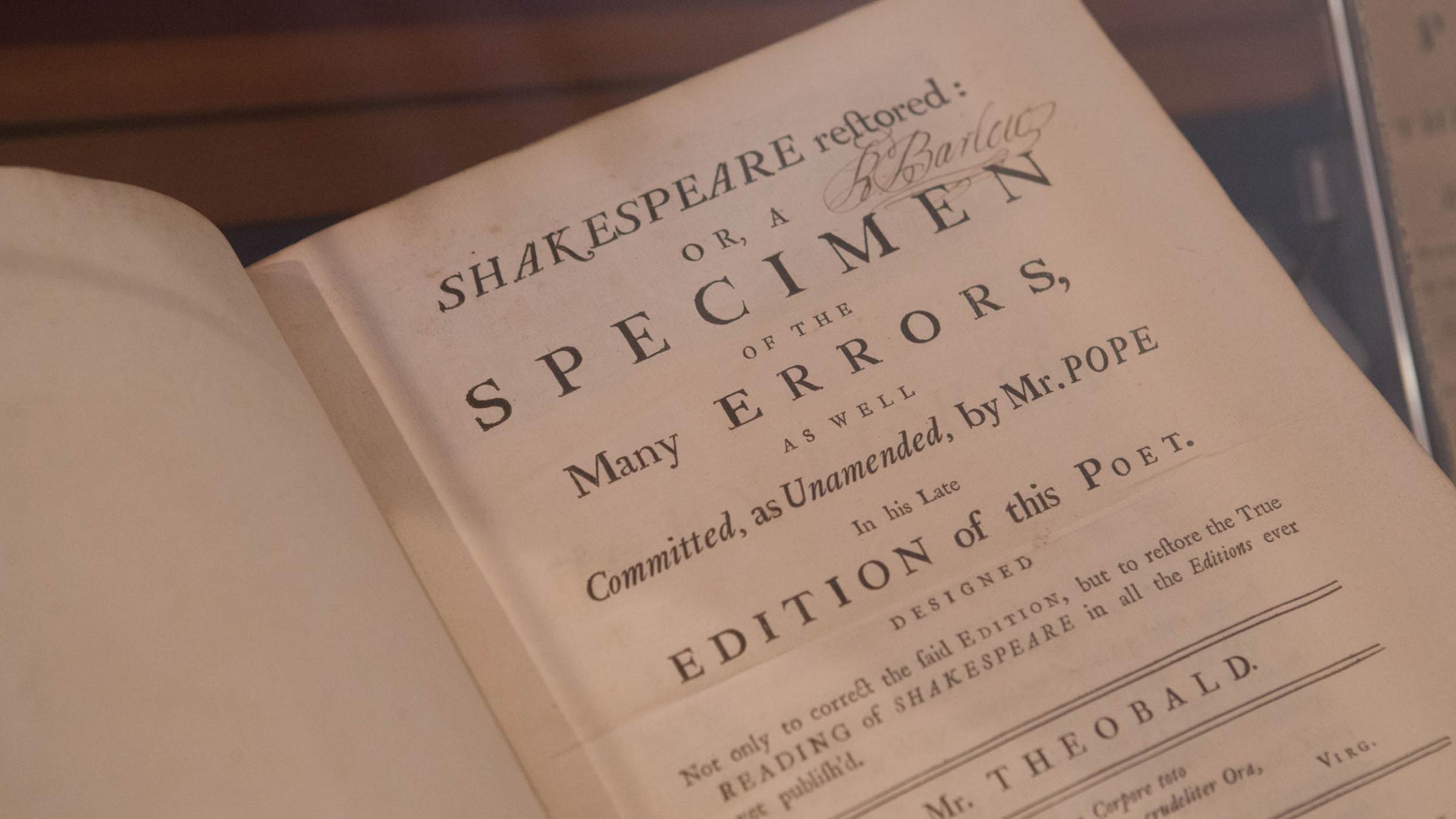

After the Pavier Quartos and the First Folio, it wasn’t long before more people started getting in on the Shakespeare publishing action. In the 18th century, editing Shakespeare became an art form and for some, a battleground.

“For the editors, it was just war. You had to be really tough, really clever and just enjoy insult if you wanted to play the editorial game successfully,” Schwartzburg said. “This was a period of verbal warfare.”

While sorting through these various editions of Shakespeare, Schwartzburg and her graduate students were tickled by the creative ways editors found to insult their peers. The curators couldn’t resist creating a list of top 10 insults to include in the exhibit.

The list includes gems like editor Lewis Theobald’s 1726 takedown of fellow editor Alexander Pope for Pope’s 1725 editing of a passage in Hamlet: “[N]o Body shall perswade me that Mr. Pope could be awake, and with his Eyes open, and revising a Book, which was to be publish’d under his Name, yet let an Error, like the following, escape his Observation and Correction.”

In the process of promoting their own work and tearing into the work of their colleagues, this era of editors created the foundations for the versions of Shakespeare we read today. They established the common editorial practices like footnotes and dramatis personae that have shaped modern English literature.

The exhibit also features some important advances in the history of the physical book. UVA owns a set of the Diamond Classics edition of Shakespeare, which is one of the first true examples of a uniform cloth binding for a set of books. Printed by William Pickering in 1825, these books represent one of the earliest steps away from expensive leather binding and toward making Shakespeare’s books more accessible to all.

The Diamond Classics edition represents an additional publishing advance in the size of its typeface. When it was published at 4.5 points in size, the Diamond’s was the smallest typeface to date. This small set of books is part of UVA’s collection of more than 15,000 miniature books and one of 150 miniature Shakespeare books that can be found throughout the exhibit.

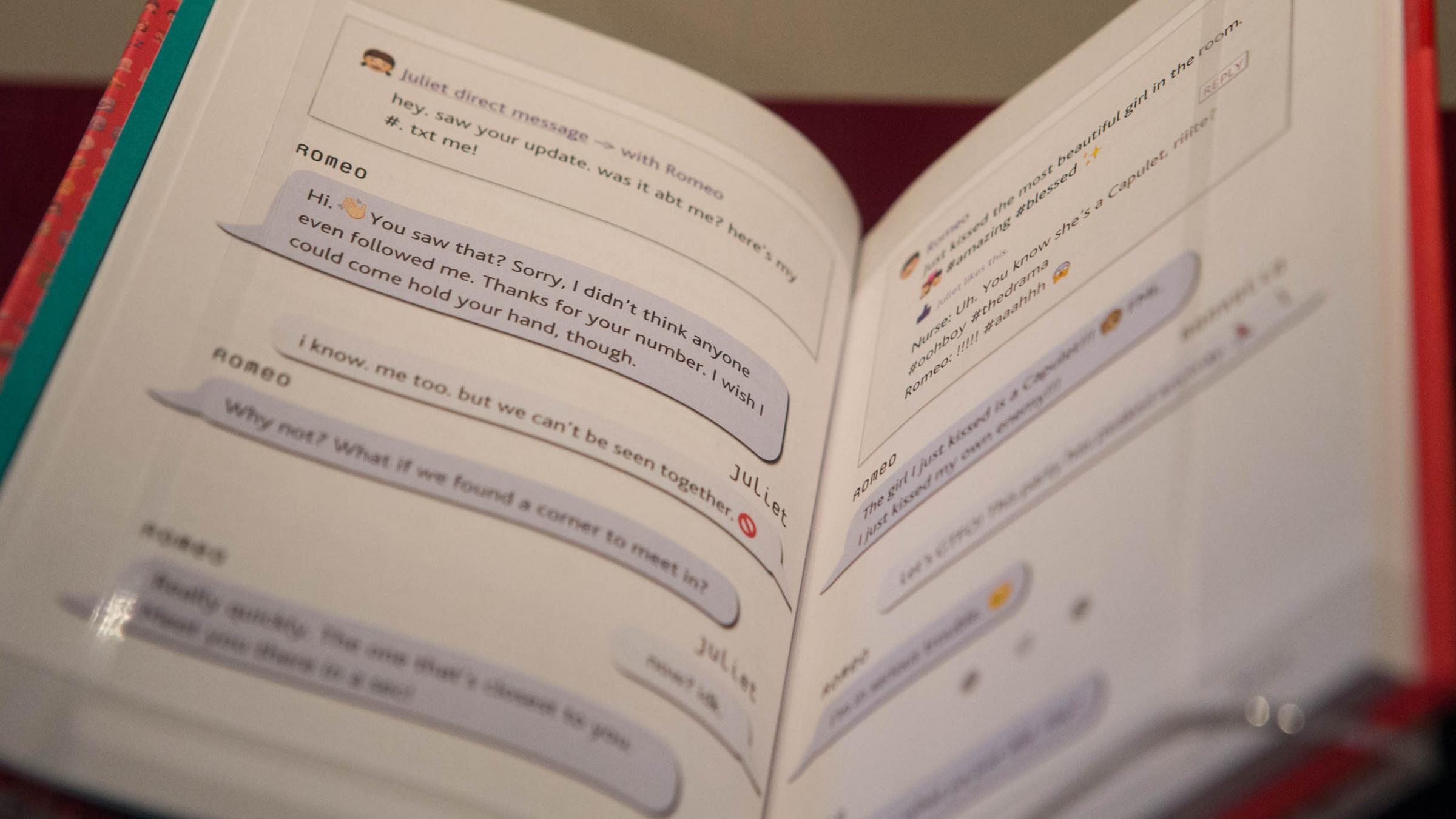

Amid its many historically significant editions of Shakespeare and rare finds like James Madison’s personal copy of “Hamlet,” the exhibition takes time to nod to the bizarre and hilarious ways that Shakespeare has been pulled into modern popular culture.

Brett Wright’s “YOLO Juliet” imagines how the love story of Romeo and Juliet might have played out if Shakespeare’s most famous teenage couple had access to smartphones and social media.

“What’s great about interpretations like this is that they’re really funny, but only if you’ve actually read the play,” Schwartzburg said. “They’re not supposed to be replacements. They’re witty accompaniments.”

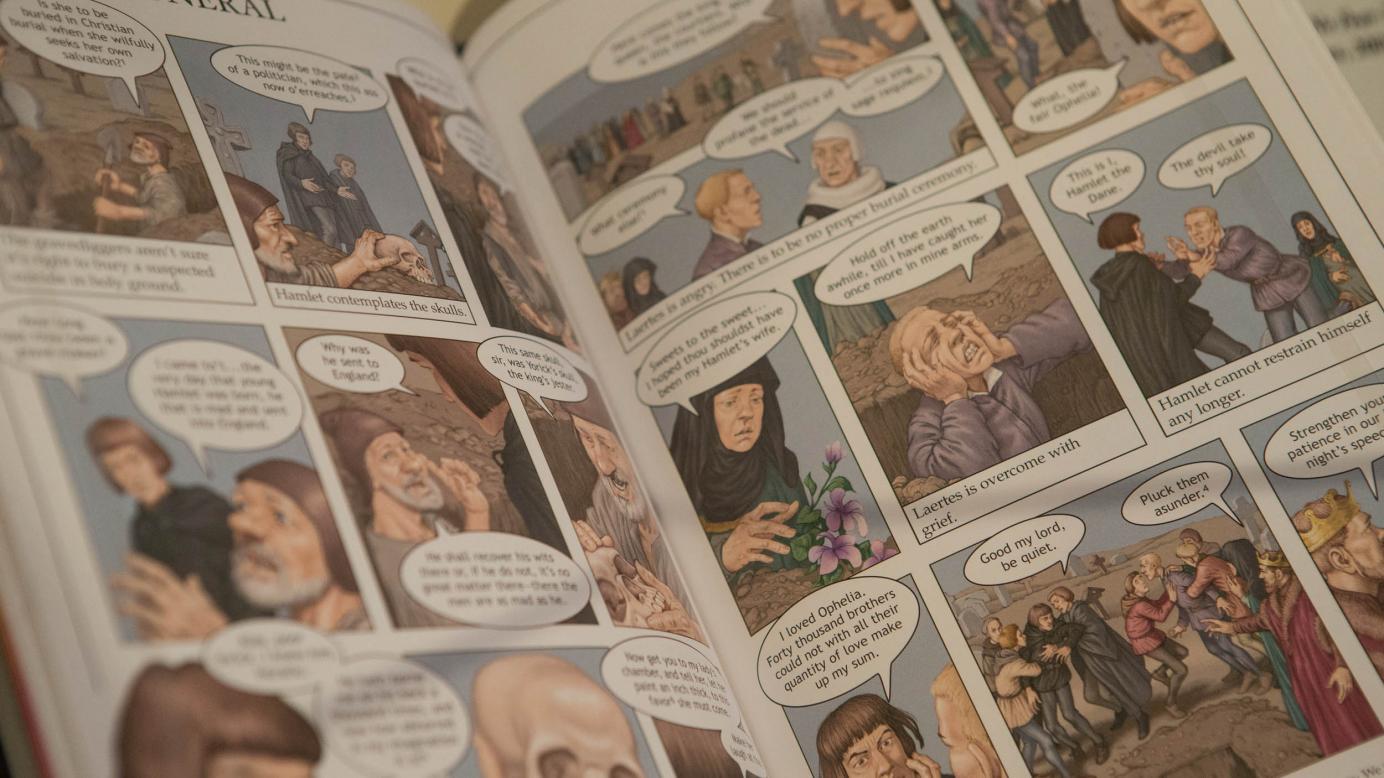

Other unusual items on display include a watch that uses flashing lights to send out Sonnets 18 and 130 in Morse code and a comic book edition of “Hamlet” designed for high school students.

Visitors will have the opportunity to visit the Special Collections exhibit through Dec. 31. The Folger’s First Folio will be on display there throughout the month of October.

Katie McNally

Original Publication – UVA Today