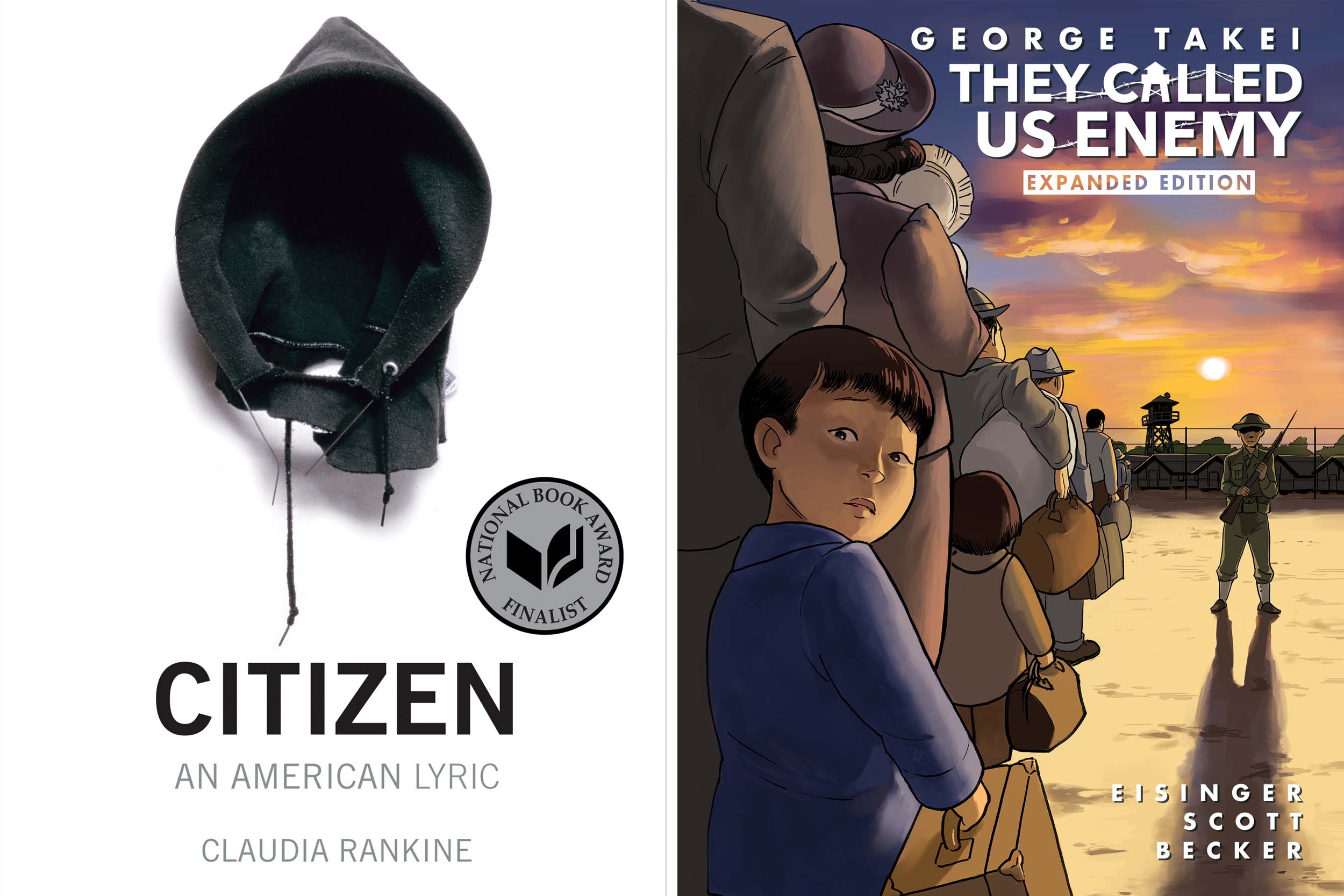

The cover of poet Claudia Rankine’s book, “Citizen: An American Lyric,” depicts a black hood from a sweatshirt jaggedly cut off at the neck, a piece of art by David Hammons made two years before teenager Trayvon Martin, wearing a hoodie when shot by George Zimmerman, was even born. That hoodie became a symbol of the racial profiling of young Black males.

A small boy whose family was forced to move into an internment camp – in the U.S. in 1942 – grew up to become a well-known actor from the 1960s TV show, “Star Trek.” George Takei’s 2019 graphic memoir, “They Called Us Enemy,” recounts his early years, growing up after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, when people of Japanese descent who mostly lived on the American West Coast were rounded up and shipped to one of 10 “relocation centers,” where they were forced to live for the next three years under armed guard.

These are two examples of readings that will likely be part of new resources for K-12 schools to teach diverse authors in the near future, thanks to local teachers and the University of Virginia’s Center for Liberal Arts.

The UVA center has undertaken a cooperative project with the Teaching Tolerance program of the Southern Poverty Law Center on “Teaching Hard Literature.” The project, which is partly funded through a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, will create a national resource to help K-12 teachers present literature associated with under-represented groups, based on surveys collected from teachers nationwide last winter.

When the Center for Liberal Arts surveyed K-12 teachers about what kind of literature they would like to learn more about to present a diverse range of authors to students, its co-director, UVA English professor Victor Luftig, thought 200 responses would be a good return. Instead, they received 1,700 responses.

“From the survey, I could see there’s a real desire on teachers’ part to have this,” said Luftig, who emphasized their “terrific enthusiasm.”

English professor Lisa Woolfork, the other co-director of the Center for Liberal Arts, and colleague Jennifer Greeson, associate professor of English, won a grant from UVA’s Institute for Global Humanities and Culture to create and conduct the national survey. Several teachers, including some in the Charlottesville area, then analyzed the survey results to determine how to make “Teaching Hard Literature” resources useful for various state standards or different priorities according to school districts around the country. That entailed looking at geographical areas, grade levels, private and public schools, and other data from specific regions.

The survey and this project have brought together faculty and graduate students from the College of Arts & Sciences and the School of Education and Human Development, Luftig pointed out. “Two Ph.D. students, Sarah Winstein-Hibbs from English and Rosalie Chung from the Education School, designed the survey that elicited those many responses, and Rosalie is writing her dissertation partly about ‘teaching hard literature,” he said.

The Center for Liberal Arts collaborated with the Southern Poverty Law Center two years ago for a similar program on “Teaching Hard History,” in response to the white supremacist marches of Aug. 11 and 12, 2017 in Charlottesville. That effort, which had an in-person workshop, also included a digital project on local history, “The Illusion of Progress: Charlottesville’s Roots in White Supremacy,” produced by UVA’s Carter G. Woodson Institute of African American and African Studies.

Where “hard history” focused on slavery initially, Luftig said “hard lit” will focus from the beginning on literature by a wide range of American authors, from well-known classics to contemporary young-adult writers addressing current issues. The teams have identified minority group literature that in many cases is not being taught at all. Or in another case, the same few texts are being taught again and again, but teachers still feel like they lack resources to teach those texts well or better – “Huck Finn,” for example.

Six teams of UVA English faculty, graduate students and experienced teachers from local schools formed this summer around specific topics. The Southern Poverty Law Center’s

Teaching Tolerance program is providing input at every stage, and the UVA Scholars’ Lab, especially Brandon Walsh, head of student programs, has given technological support, Luftig said. The teams are developing prototypes this fall and will field-test them in Albemarle Public Schools and other local schools next year.

The prototypes might focus on a single text or take a broad view of a topic or minority group and include resources such as lessons and learning plans. Thus, Woolfork’s team is working with Rankine’s “Citizen” and retired English professor Stephen Railton’s team will focus on Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

Greeson, who chairs American Studies, leads a team that will create a resource for teaching dialect and provide supportive materials consisting of a related range of short stories that seem of interest based on the initial survey.

Carmen Lamas, an assistant professor of English and American Studies, is leading two teams, one, with School of Education and Human Development professor Natasha Heny, using the young adult fantasy/adventure series, “Shadowshaper Cypher,” by Daniel José Older. Set in Brooklyn, the books feature a teen who’s Afro-Boricua (from Borikén, the original name for Puerto Rico; it describes those Puerto Ricans who are of African descent) and what happens when she finds out she is a “shadowshaper,” tasked with preserving and protecting her community’s cultural and historical legacy. The series addresses such topics as gentrification, police violence against Afro-Latinx communities, surveillance of Latinx children in schools through the use of metal detectors and unannounced searches, as well as youth incarceration.

Lamas’ other team is compiling a survey of Latinx literature by national-origin group.

“We will provide a short history of each national origin group and their migration stories in order to help teachers and students understand and contextualize the different experiences of each group and the cultural, ethnic and racial diversity of Latinx communities,” she wrote in describing their work. Their prototype will concentrate on Guatemalan American history, migration and culture through such texts as the award-winning middle-grade novel, “The Other Half of Happy,” published by Rebecca Balcárcel in 2019.

Looking at Asian American literature, Sylvia Chong, an associate professor of English and American Studies, also said she would like to bring attention to the breadth of nationalities and ethnicities that make up the broad Asian American category, as well as an introduction to Asian literature.

Her team is considering highlighting another example in addition to Japanese American experiences that has a very different history: literature on Vietnamese Americans who came to this country as refugees after the Vietnam war.

“These refugees didn’t intend to immigrate,” Chong said, “but the circumstances of the war and its aftermath forced their hand. Many were traumatized and remained silent about their journey, but now younger generations are writing about their experiences as well as those of their parents.”

Before the war, there wasn’t a sizeable Vietnamese American community in this country; today, they number almost two million and are the fourth largest Asian ethnic group in America.

The group might include another graphic novel, Thi Bui’s “The Best We Could Do,” a Vietnamese-American woman’s memoir. Published in 2017, it tells of her family’s past in escaping Vietnam during the war and coming to the U.S. When Chong taught in the College’s new Engagements curriculum, this was a required first-year reading.

In addition, Viet Thanh Nyugen, whose 2016 debut novel, “The Sympathizer,” won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, may also make the list of readings with his short story collection, “The Refugees,” Chong added.

One of the team’s goals, Chong said, is introducing a different way of reading Asian American literature that’s not about culture. Instead of only emphasizing rituals or traditional cultural elements that may make Asian Americans seem exotic or separate from other Americans, her team is focusing on the history of how Asian peoples came to the U.S. – some more than 150 years ago – and the struggles they and their descendants have faced.

Takei’s book, just published last year, focuses on what life was like in the internment camps that were located in inhospitable places out in the western U.S., while World War II raged on in other lands across other shores.

This history is but one thread in the fabric of various experiences that Asians and Asian Americans have had in this country. And this diversity, let alone literature, is seldom taught in high school or middle school, Chong said.

Likewise, Woolfork said, “there are high schools where no Black authors are taught. Zero.”

Woolfork called “Citizen” a beautiful book.

“The book itself is like a collage with photos, articles, vignettes written in second person to impress upon the reader the emotional weight of microaggressions and racist harm.”

She added, “I’m looking forward to the model our team is developing with curricular ideas teachers can bring to their own schools,” and said her team is excited to work on this project.

One member is 2011 UVA alumna, Olivia (Hudson) Gause, who double-majored in English and African American Studies, and worked with the Virginia College Advising Corps after graduating, a job that led her to the classroom and teaching. She just began her eighth year teaching at Lake Taylor High School in Norfolk.

Gause wanted to participate in the Teaching Hard Literature Project, she said, to learn more about and promote culturally relevant and responsive lessons and resources that educators could confidently bring to their students, colleagues, curricula, departments and districts.

“I’ve already taken pieces of what we’ve discussed and worked on so far and added it to my syllabus. And I’ve suggested the book our group is working on – Claudia Rankine’s “Citizen” – to my friends at work to consider for their own lessons,” Gause said.

Having Woolfork as an instructor also was one of the biggest influences on her academic, professional and personal life, she added.

The project addresses pieces “of the larger puzzle of white supremacy in America, its racism and anti-Blackness,” Woolfork said.

This work is very much in line with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s projects, she said, as it will be part of the center’s Teaching Tolerance umbrella of initiatives. It’s also in line with Gov. Northam’s recent efforts and commission to require African American history in K-12 schools.

“I’m honored to be working in community with public schools,” Woolfork said. “I think UVA should do whatever we can to support and provide resources for the benefit of all Virginians.”

Original Publication: UVAToday