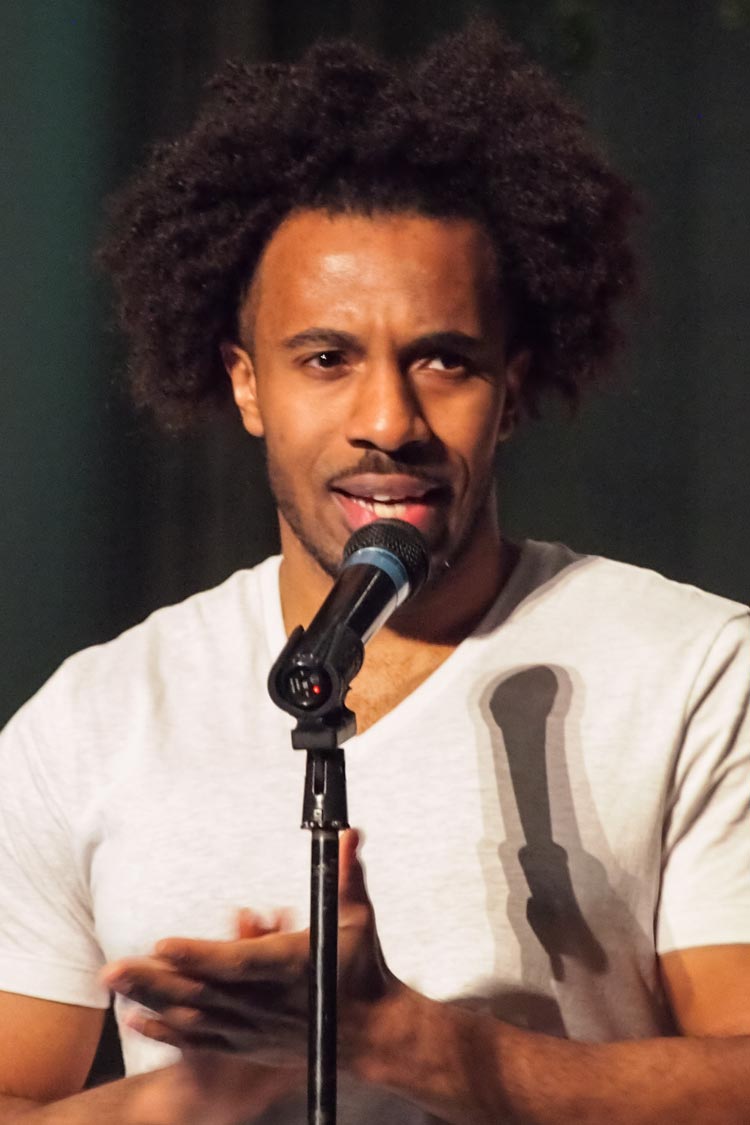

From being a “promising writer” who used to compose love poems for his high school friends to becoming the director of a creative writing program, University of Virginia alumnus Kyle Dargan has found much success and satisfaction as a poet and teacher, which he began to develop during his time on Grounds.

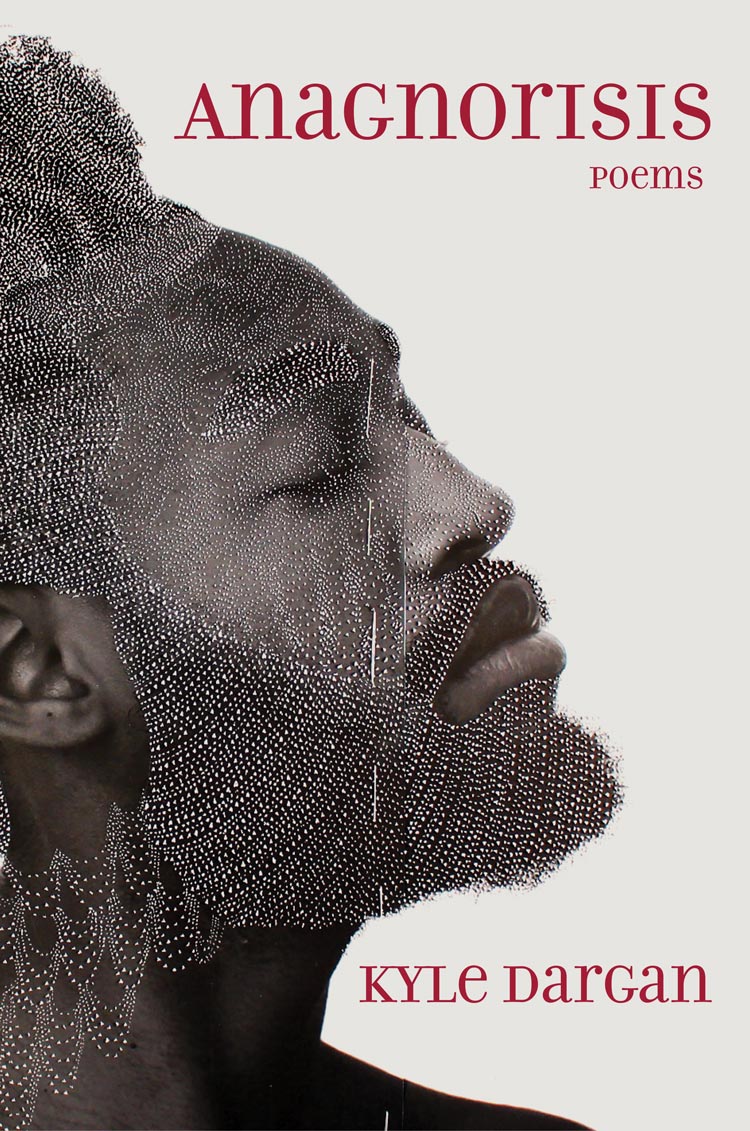

Dargan’s new book, “Anagnorisis,” according to reviewer Imani Perry, is “a book of riveting intimacy and of national significance; a reckoning with this terrifying immediate moment: Trump-times and macho disasters. Yet it is also a book of unsentimental and profound hope in flesh and blood everyday-living people. It is a book of ‘Dee Cee’ and a book of America.”

After he earned his undergraduate degree from the University, he earned an M.F.A. from Indiana University. Along with publishing his fifth book of poems, Dargan, an associate professor of literature at American University, where he directs its creative writing program, has received the Cave Canem Poetry Prize and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award.

Bill Moyers interviewed Dargan for his PBS show, “Moyers & Company,” in 2013. The same year, Dargan gave a TED Talk hosted by the Ellington School of the Arts. During the Obama administration, Dargan partnered with the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities to produce poetry programming at the White House and Library of Congress. He has worked with and supports a number of youth writing organizations, such as 826DC, Writopia Lab and the Young Writers Workshop, the latter a UVA summer arts program for teens.

Dargan will read poems, including some from his new collection, at the New Dominion Bookshop on Friday at 7 p.m. Fiction writer Crystal Hana Kim, who just published her debut novel, “If You Leave Me,” joins him.

Before Dargan returns to Charlottesville, he answered several questions from UVA Today about the place of poetry in his life.

Q. You were in the first cohort of majors in this new Area Program in Poetry Writing at UVA, right? Why did you want to pursue this program?

A. The truth is that I cannot say I knew I wanted to. Lisa Spaar – being the visionary that she is – had this idea that she could get the program off the ground with the special group of young poets she had. (And it was unique. You can ask her.) I came to UVA for the English department and the writers based there – as crazy as that sounds for an 18-year-old at that time. Thus, I was already so invested in poetry by the time I arrived at my fourth year that to not take the additional step with the APPW just would not have made sense.

I have no regrets today, obviously.

Q. What stands out about your education at UVA? How did the program help you decide you wanted to pursue a career in poetry and teaching (or would you put it differently)?

A. I don’t think one has a career in poetry. It is a passion – a calling we fit into our days of labor and paying bills and caring for family. I also remind people that I teach and edit for a living. I do not “do poems” to pay my mortgage. I write because – up to this point – I have felt compelled to do so.

As for my UVA education’s role in that, I imagine that you can look at my first book, “The Listening,” and find all types of UVA Arts & Sciences learning throughout that book, as well as the lived experiences of being in Charlottesville at that time. I was a transfer student.

I wasn’t admitted to UVA when I applied out of high school, but I fought my way in because I just had this sense that it was where I needed to be as a young thinker and budding writer, and I tried to make the most of it at a time when I was still learning who I was. I worked with great faculty there – like Lisa Spaar and Rita Dove and Charles Wright and Stephen Cushman and Jeb Livingood and Kyle Thompson and James Cargile and Charles Rowell – who really modeled an ambitious human intellectual life for me. You never lose that.

Q. How did you get into poetry writing in the first place?

A. I wrote “love poems” for money at my all-boys Catholic high school – pieces my buddies would give to the girls they were trying to woo. I outgrew that, thankfully.

My school had a little poetry club, and one of the teachers that moderated it, Mr. Onion, gave me a copy of Rita Dove’s “Selected Poems” to read. That was also part of my beginning a path toward UVA.

Q. Your fifth book of poems is called “Anagnorisis.” How did you come up with that?

“Anagnorisis,” the title of Dargan’s fifth book of poetry, refers to the moment of revelation about one’s condition and one’s adversaries ahead of a reversal of fate, Dargan said.

A. The idea has always interested me since, as a teacher, I used Aristotle’s elements of Greek tragedy – hamartia, peripeteia, catharsis and anagnorisis – to analyze Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” and Willy Loman specifically as a tragic hero.

The idea of anagnorisis – the moment of recognition or revelation about one’s condition and one’s adversaries ahead of the big moment of reversal of fate – felt fitting for what I was experiencing as a black American in the two or three years leading up to the current political moment and presidency. There was something to be firmly and finally accepted about one’s “countrymen” (as James Baldwin might say) given what exactly was articulated in the campaigning leading up to November 2016 and the actual vote itself. I was not naïve, but I did not think there was enough xenophobic and protectionist sentiment to send the country this far into civic regression. But here we are – in some ways caught in a collective fall as a country.

The poems both capture my personal experience of that beginning tip toward tumbling and my sincere and unassuageable disappointment in those who found peace in tilting America this way.

Q. I understand you have worked with youth clubs or writing groups, besides directing American University’s creative writing program. Why do you think it’s important to encourage young people to write poetry?

A. If you introduce it the correct way, I don’t think you have to encourage youth to write poetry. Language play is a rite of passage. We have all engaged in it in one way or another – be that dabbling in forbidden language or inventing our own generational lexicons and phrasings.

Rather, I find myself doing a lot of work to undo the effects of interpretation – and analysis – heavy poetry pedagogy at the middle and high school levels. Once you have beaten it into someone that poetry is like math – that there are mostly right and wrong answers to the question of what it means – congratulations. You’ve created an adolescent who will likely despise “poetry” (i.e. what you taught them it was).

But if you give children and teens space to appreciate and articulate what poems “do” to and for them, they will flourish as readers and writers. It is also important, too, that you give children and teens work that they can see themselves within. If all you ever read are texts and poems filled with characters and environments that in no way reflect your own experience, you are going to have a strained relationship with reading.

Q. Poetry appears to be experiencing an upswing in popularity. Why do you think that might be the case right now?

A. To my point directly above, I just think some of the walls protecting the American and English canon are coming down and the diversity of voices receiving space in the different facets of America’s literary life begets more readers of diverse backgrounds. I cannot keep up with the proliferation of voices, and that was very much not true only a few years ago. And that does take people being able to relinquish or share some of the power they have historically monopolized as editors and publishers and awardees and general arbiters of what American literature will be.

Honestly, we are now seeing the fruit of shifts that began in the 1980s and ’90s. So imagine where things will be 20 years from now.

Q. On your website you say that you have two other books already planned. How do you know that already? Are they based on themes or poems already written?

A. Well, the first “book” I wrote was my undergraduate thesis for the APPW, now 16 years ago. I had no idea what I was doing then. Now, all those years and five books later, I have gained a sense of what has the momentum and urgency to become a worthwhile and sustained book project. I have maybe three or four other ideas for books in addition to those two plotted, but they have yet to earn my faith.

But I don’t really know about my future as a writer. Writing books – or I should say, publishing books – is not something I do for my health. At this point, it is mostly for my audience. They get the most out of it.

The thing about publishing books of poems is that the “rewards” margins are very narrow. Very few are best-sellers (in a purely capitalist sense) and there are only but so many worthwhile yearly accolades to go around. Add to that the fact that the process itself is extremely lonely, and you can realize how psychically fraught a venture it is. So I may abandon poetry soon – not writing individual poems, but putting my mind and body through the process of publishing books. I might shift to essay collections instead. I have ideas for film scripts and comics or graphic series.

I have given a lot to poetry and it has given me some wonderful opportunities in return, but over time – given what I put into my books and the larger poetry community – I have definitely felt the return diminishing. Better to evolve – even if away from what you have loved – than to become embittered as an artist.

Anne E. Bromley

University News Associate

Office of University Communications

Original Publication: UVA Today